For a few months, I've intended to revisit my 'Quantum vs NP' post pointing out mistakes in Zachary B. Walters' claimed linear-time 3SAT paper. Walters commented on the post, and there was some back-and-forth, but we still disagree over whether his algorithm works. (I'm the one who thinks it obviously doesn't.)

One of the mistakes Walters makes is actually a widespread misconception, so I figured I should talk about it separately. Thus this post.

Lay Erasure

Here's a typical lay summary of a quantum eraser experiment, from Brian Greene's 'The Fabric of the Cosmos':

even though we've done nothing directly to the signal photons, by erasing the which-path information carried by their idler partners we can recover an interference pattern from the signal photons

This explanation isn't wrong, because Brian has something very specific in mind when he says "can recover", but it's seriously misleading. Even worse, it's misleading in a way that most explanations of eraser experiments are. Specifically, I bet most readers end up thinking the interference pattern simply re-appears, as if the idler photon had never existed. (Don't believe me? Consider the many many posts on physicsforums with that exact misconception.)

(Sidenote: While searching for bad lay explanations, I stumbled on The quantum eraser demystified. It's well done, assuming you understand code. If only it didn't fall prey to the misconception I'm complaining about...)

The misconception isn't limited to just lay audiences, either. Walters is no slouch, and I really don't want to single him out, but then there's this paragraph from his paper:

Measuring the projection of the scratch bit along [the Z] axis would resolve which branch of the conditional statement was executed, and destroy the probability for states which correspond to the other branch. Instead, this information is deliberately destroyed by nonselectively measuring the scratch bit [along the X axis].

Clearly a lot of people think that measuring one qubit can directly affect another. So what's actually going on?

What's Actually Happening

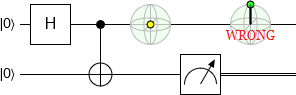

People think that the quantum eraser works like the following circuit, where an operation on one qubit affects the state of another:

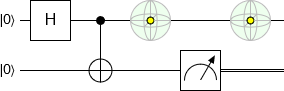

But actually, in the depicted situation, the other qubit is always unaffected:

You can never observably affect one qubit by operating on another. It doesn't matter how complicated you make things. Doing so is a trivial violation of the no-communication theorem.

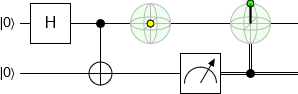

Actual eraser experiments get around the no-communication problem by conditioning:

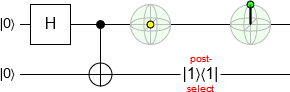

However, we often think of this conditioning in terms of post-selection. We throw out all the runs that don't meet some criteria, and look at the remaining ones:

Note that the last circuit looks quite a lot like the misconceived circuit I started with, but they mean very different things in practice. Measurement doesn't require coordination, but post-selection does: if Alice has the top qubit and Bob has the bottom qubit, Bob has to tell Alice which runs she needs to throw out.

Surprisingly, describing experiments in words has the same post-selection-sounds-like-measurement issue that the circuit diagrams do. It can be hard to spot the distinction.

For example, consider the quantum eraser experiment that starts with a two-slit experiment but covers one slit with a horizontal polarizing filter and the other with a vertical polarizing filter. The idea is that each photon's polarization contains the which-way information and, by placing a diagonal polarizing filter after the slits, both the horizontally and vertically polarized photons end up diagonally polarized (thus erasing the which-way information and allowing the interference to re-emerge).

Did you catch the post-selection?

The diagonal polarizing filter throws away half of the photons. If you looked at the missing half, you'd find it contained an exactly complementary interference pattern. Put the two together (i.e. do the measurement but not the post-selection), and the result is no apparent interference pattern.

Consequences

As I've already mentioned, this confusion between measuring and post-selecting is quite common.

Because post-selection requires comparing notes after the fact, but measuring doesn't, there's a never-ending stream of people claiming erasure allows for FTL communication. And sometimes more sophisticated variants appear, like claiming erasure gives your quantum algorithm a novel non-unitary primitive to work with.

It's a problem.

Closing Remarks

Erasing an entangled qubit's value requires an interaction between that qubit and its entangled partners (example).

For all intents and purposes, post-selection counts as an interaction.

It's easy to confuse measurement and post-selection. Especially when grouping results, or using polarizing filters. Be careful.