When it comes to quantum things, self-learning can be a tricky business. A strange surprising answer could be due to quantum mechanics being counter-intuitive... or it could be because you made a stupid mistake in line 3. There's a good chance of fooling yourself, when you can't tell the difference between the odd and the wrong, between apparent paradoxes and actual paradoxes.

As a person who's trip into learning quantum things was initially ad-hoc and lacking in textbooks, I ran into this problem several times. Let's look at one encounter, where I accidentally ate some probability.

Playing with Photons

My first foray into actually understanding quantum things was toying, on paper, with optical interferometers. Starting that way wasn't intentional, I just happened to come across a straightforward walkthrough of computing what happens for a given a setup of beam splitters, mirrors, and detectors. Knowing the math turned something confusing into something sensible, so I started exploring.

(Side note: actually I did take a modern physics course in university earlier on, but I don't remember the QM part being particularly enlightening. I remember it more like... "here's the calculus problem that corresponds to situation X". Maybe the core ideas were there, but I didn't catch on to them at that point.)

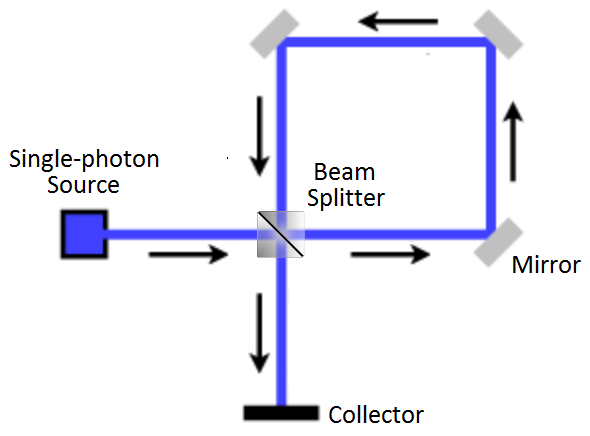

One of the interesting setups I tried was making a loop: using three mirrors and a beam splitter to send a photon round and round. The idea was that photons would decay out of the system instead of leaving immediately. Here's a simple interferometer with a loop:

A photon trapped in the loop effectively has a (very short) half-life. Every time it goes around, there's a 50/50 chance of escape. You can tell whether or not it's escaped yet by using the collector.

If the collector was a normal detector, e.g. one that makes an audible click when hit by a photon, then hearing the click would let you know that the photon escaped.

But I didn't want the collector to be a normal detector.

I was interested in making the photon's various possible paths, which had different arrival times, interfere with each other. So I assumed a different kind of collector, which I'll call a "quantum latch" here. The quantum latch is very simple: it stores a qubit, and whenever a photon hits (and is absorbed by) the latch, the qubit is toggled.

Spoiler alert: the previous paragraph describes an impossible device. But for now let's continue like I did, blissfully ignorant, and see what symptoms result.

The basic operational idea behind the latch is that, by measuring its qubit, you can find out whether or not the photon was absorbed yet. Is the qubit still Off, as it was before you released the photon? Then the photon was still in the loop when you measured. By running multiple experiments and measuring the latch at different times, you can track how the photon decays out of the loop and into the latch's qubit.

Decaying Probabilities

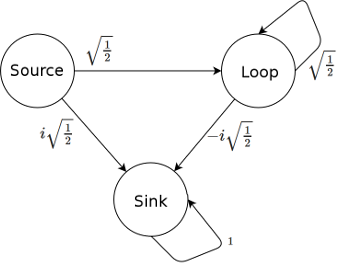

Assuming the collector in the above diagram is a quantum latch, the optical system simplifies down to three basic states: photon emitted from source ("source"), photon trapped in loop ("loop"), and photon caught by latch ("sink").

The flow of amplitudes between the states is not overly complicated: photons gain a phase factor of $i$ whenever they're reflected, and get evenly split between the passed-through and reflected-by cases when encountering a beam splitter. Here's a markov diagram of the amplitude flows:

Initially, at step 0, all of the photon-is-here amplitude is in the "source" state. Then half of it passes through the beam splitter unaffected and moves into "loop", while the other half gets reflected by the beam splitter into "sink" (gaining a phase factor of $i$ from the reflection). Now amplitude in "loop" is reflected three times, and half of it passes through to "sink" (net phase factor $i^3 = -i$) with the other half being reflected back into the loop with no net phase factor because $i^4=1$. Once the system is in the sink state, it stays there.

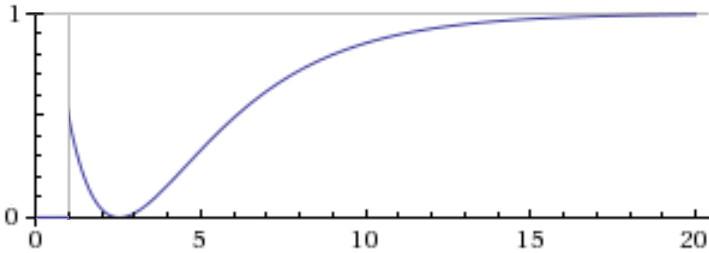

Tracking the amplitude flows over several steps, and calculating the probability of finding the system in the sink state (by squaring the magnitude of its amplitude), shows something odd is happening:

| Step | State (note: $s = \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}}$) | Sink State Probability |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | $1 \ket{\text{source}} + 0 \ket{\text{loop}} + 0 \ket{\text{sink}}$ | 0% |

| 1 | $0 \ket{\text{source}} + s \ket{\text{loop}} + i s \ket{\text{sink}}$ | 50% |

| 2 | $0 \ket{\text{source}} + s^2 \ket{\text{loop}} + (i s - i s^2) \ket{\text{sink}}$ | 4.3% |

| 3 | $0 \ket{\text{source}} + s^3 \ket{\text{loop}} + (i s - i s^2 - i s^3) \ket{\text{sink}}$ | 2.1% |

| 4 | $0 \ket{\text{source}} + s^4 \ket{\text{loop}} + i (s - s^2 - s^3 - s^4) \ket{\text{sink}}$ | 15.7% |

| ... | ||

| $n$ | $0 \ket{\text{source}} + s^n \ket{\text{loop}} + i \parens{s - \sum_{k=2}^n s^k} \ket{\text{sink}}$ |  |

| ... | ||

| $\infty$ |

$0 \ket{\text{source}} + s^\infty \ket{\text{loop}} + i \parens{s - \sum_{k=2}^\infty s^k} \ket{\text{sink}}$ $= i \parens{s + 1 + s - \sum_{k=0}^\infty s^k} \ket{\text{sink}}$ $= i \parens{2s + 1 - \frac{1}{1-s}} \ket{\text{sink}}$ $= i \parens{2s + 1 - (2s + 2)} \ket{\text{sink}}$ $= -i \ket{\text{sink}}$ |

100% |

Do you see it? The probability goes down for steps 2 and 3! Intuitively, the probability that the photon has escaped from the loop should be increasing monotonically towards certainty... but instead it dips before slowly climbing to 100%. Is the photon leaking back into the loop? How is the latch doing this?

(Even more serious problem: the total probability at each step doesn't add up to 100%! But that's not what I noticed at the time.)

I was initially tempted to come up with crazy physical interpretations of what's happening, or to dismiss the thought experiment's outcome as just typical quantum weirdness, but the truth is much more mundane: weird things are happening because I was dumb and broke the rules. The supposed "quantum latch" is a malformed idea, disallowed by the postulates of quantum mechanics.

Oops

The evolution of a quantum state is guaranteed to be reversible, because the evolution is always unitary. (Even measurement can be thought of in a reversible way, though it's typically not thought of that way.)

With that in mind, suppose we're working with our source/loop/sink system and happen to know that the system is currently in the $\ket{\text{sink}}$ state. We want to move backwards by one step; what is the preceeding state?

One possible preceeding state is $\ket{\text{sink}}$, since amplitude stays in $\ket{\text{sink}}$ once it's there. But there's another valid solution, based on interfering combined contributions from the source and loop states: $i \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{\text{source}} - i \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{\text{loop}}$ also works as a preceeding state. Two distinct possible preceeding states are getting mapped to the same final state; clearly this is not reversible!

The root problem is my supposed quantum latch absorbing the photon. When you run time backwards, and you know a photon was absorbed by the latch, the state of the system doesn't say when to un-absorb that photon. Was it absorbed a nanosecond ago? Twenty years ago? You can't tell, and this prevents you from reversing the evolution.

So the quantum latch is impossible; it violates the unitarity postulate of quantum mechanics. In fact, it exemplifies why the evolution has to be unitary: intermediate steps had possibilities that didn't add up to 100%! It was just an unlucky coincidence that the layout I chose obscured the problem by converging to a 100%-photon-in-sink state, instead of something ridiculous like 256%-photon-in-sink. That's the kind of thing that happens when your quantum operations don't preserve total squared magnitude.

One way to fix the problem with the latch is to have it store the photon absorption times. For example, we could have the latch store an integer instead of a bit, have the photon trigger the 0-to-1 transition, and increment non-zero values after each time step. Then, when running things backwards, we know the decrement from 1 to 0 is when the photon is un-absorbed. All these new latch count states would distinguish between early-arrival paths and late-arrival paths, preventing interference between them... which may be boring, but at least the probability of escaping the loop won't see-saw.

Summary

Quantum state transitions must be reversible.

A device that absorbs a photon to flip a qubit is impossible, because time-of-arrival information is lost and that breaks reversibility.

When you break reality's rules without realizing, weird things happen.