I had a bit of a surprise this week. Despite never publishing a paper, I've been cited in one! The preprint "Factoring using 2n+2 qubits with Toffoli based modular multiplication", by Häner et al., cited this answer on cs.stackexchange. The answer is me summarizing a few of the tricks I found while trying to solve an exercise in Nielsen and Chuang's textbook.

So I figured I'd spend a post discussing one of the problems addressed by the paper: adding a compile-time constant into a qubit register.

Adding Constants vs Adding Variables

Surprisingly, reversibly adding a constant into a register is harder than adding a register with an unknown value into another register.

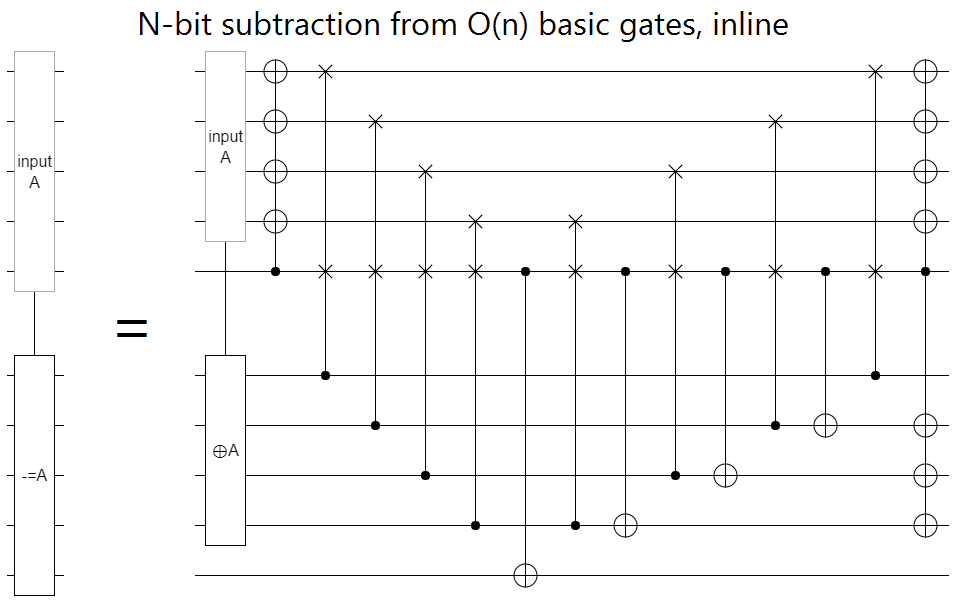

For example, in the post Constructing Large Increment Gates I cited the VanRantergem adder and its ability to add one register into another with a linear number of gates using only one OFF ancilla. Since then, I found a way to avoid the ancilla:

(Note that the above is a subtraction circuit. To do addition you just run the circuit in reverse order. Also note that, when reducing the circuit to a quantum gate set, or even just replacing the Fredkin gates with three Toffoli gates, many of the operations simplify by constant factors.)

Usually, you would expect that specializing a circuit to apply to only a single case (i.e. adding a constant instead of a variable) would reduce the amount of work. That intuition doesn't work here because, when you're adding a compile-time constant, you don't have a source register to use as workspace. The above circuit has operations that temporarily modify the source register. Without those operations, without the source register, the circuit doesn't work!

Of course you can just assert that you have workspace, but where's the fun in that? Also, in the context of Häner et al.'s paper, asserting you have that workspace would increase the required number of qubits by 50%. If we suppose that quantum computer capacities will grow in a Moore's-law-like fashion, that's an extra year of waiting to run your circuit!

So clearly the first order of business is dealing with the fact that we don't have workspace.

Finding a Borrowable Ancilla

In a classical reversible circuit it's sometimes impossible to take an operation that touches every bit and reduce it into smaller operations (there are permutation parity issues). But in a quantum computer, where even the NOT operation has a square root, reduction is always possible.

(The ancilla we free up will be in an unknown state, and we have to restore it to that state once we're done with it. Häner et al call these "dirty borrowed" ancilla. I just call them "borrowed".)

Consider that, if the constant we want to add into a register is even (i.e. its low bit is OFF), then the low bit of the target register is effectively not involved in the operation. When you add an even number into a register, you don't change whether that register is even or odd. So, when the constant-to-add is even, we're already done. Just use the register's low bit as the borrowable ancilla.

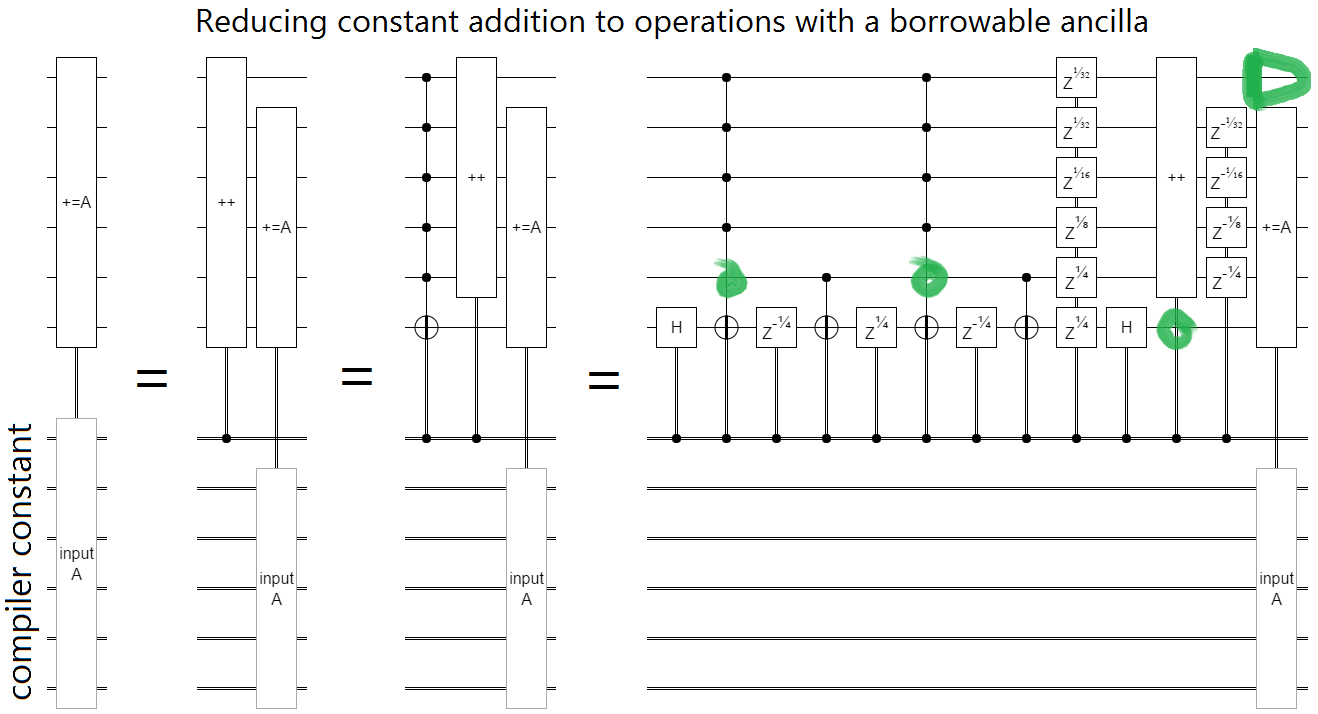

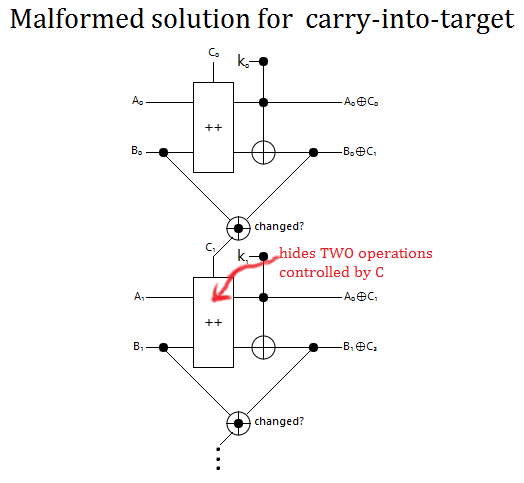

To deal with the other case, where the constant is odd, we simply apply a fixup operation: an increment. After we've done the increment, we can again ignore the target register's low bit and use it as a borrowed ancilla. In effect what we're doing is applying a "controlled" increment, except the control is a compile-time constant. Really the increment will just be there or not be there, but in diagrams I'll show it as a controlled operation.

We reduced the size of a constant-addition by pulling out an increment... but now the increment covers every bit. To reduce the increment gate's size, we pull the take-out-a-simpler-operation trick again. This time we pull out a many-controlled-NOT.

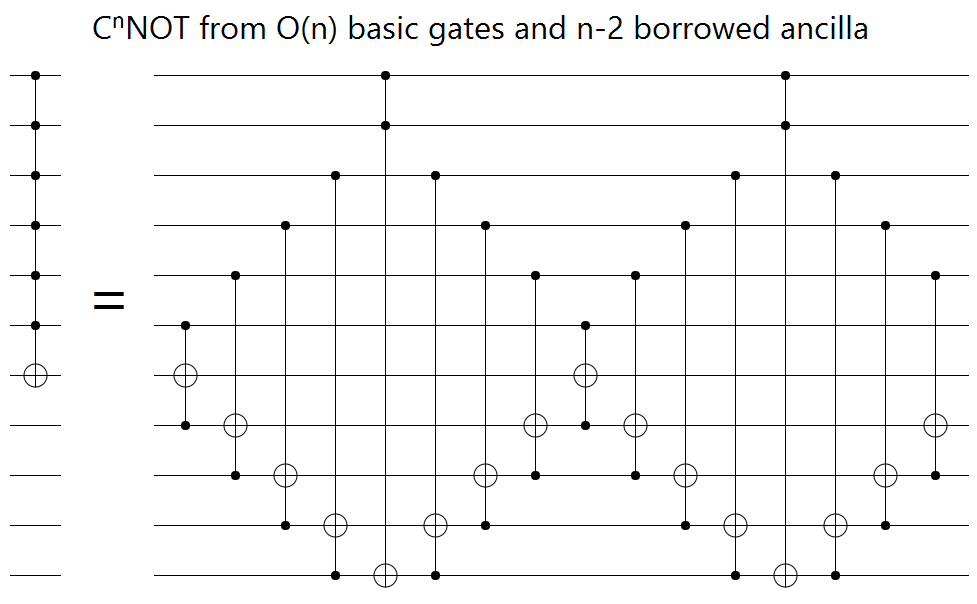

Fixing the fact that the many-controlled-NOT touches every wire is more complicated. We need quantum operations. I won't go into the details here; see the post Using Quantum Gates instead of Ancilla Bits if you want them.

After pulling an increment out of the constant-addition, pulling a many-controlled-NOT out of the increment, and using quantum operations to reduce the size of the many-controlled-NOT, we're left with a circuit that has at least one free qubit available to borrow at all stages:

The green circles are just pointing out where each large operation's free qubit is.

The next order of business is reducing those large operations into basic ones.

Reductions

Now that we have a borrowable ancilla to work with, we can use classical constructions that cut operation sizes in half instead of complicated quantum ones that only cut sizes one bit at a time.

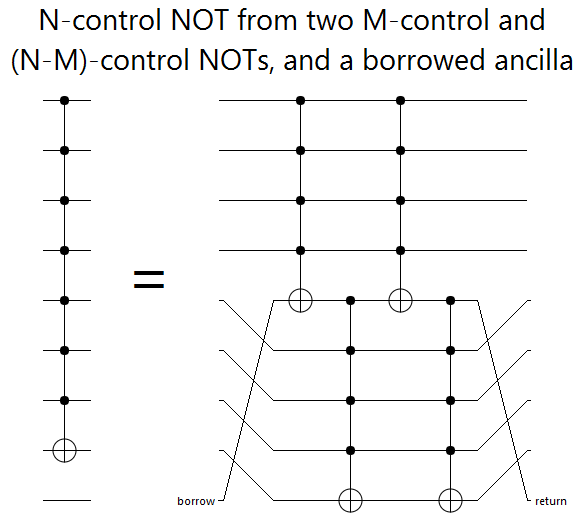

We can cut Controlled-NOT sizes in half with this construction:

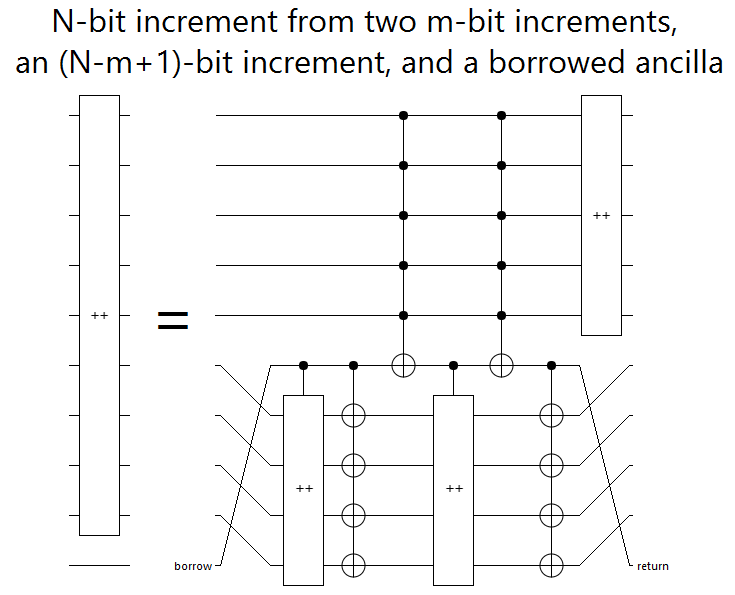

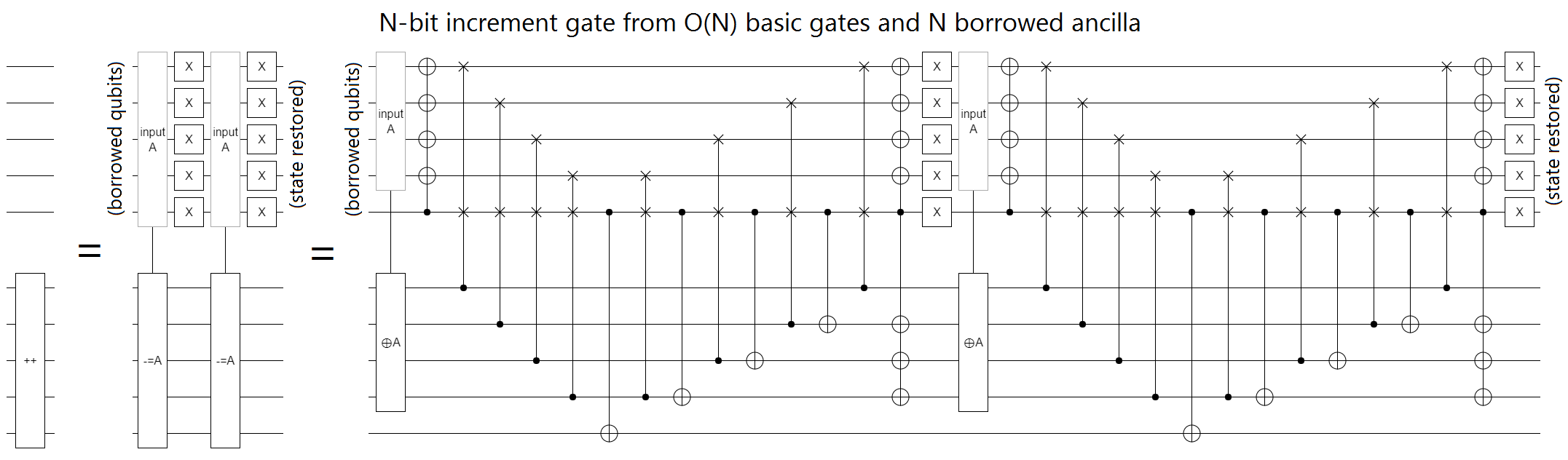

And we can cut increments in half like this:

There's also a way to cut constant-additions in half, given in Häner et al.'s paper, but we'll talk about that later.

The halving constructions would be inefficient if iterated. However, the half-sized operations we created after just one iteration have so many unused bits available to borrow that we can use alternative constructions that don't involve recursing.

Here's how you turn a half-sized Controlled-NOT into basic gates:

For increment gates, the half-to-basic circuit looks very elaborate. But really it's straightforward: when you subtract both $x$ and its bitwise complement out of something, you've shifted the target by $-x - \neg x = -x -(-x-1) = +1$. We do the subtractions using the linear-inline-subtraction construction I showed earlier:

(I avoided doing obvious cleanups on the circuit to keep the structure clear.)

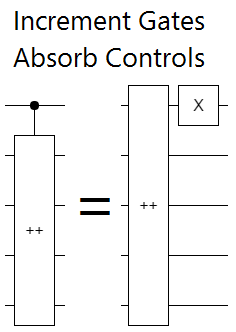

Some of the constructions so far have used controlled increment circuits. These are no harder than doing an increment. Increment gates absorb controls into their low end:

Now the only operation left to cut down to size is the constant-addition.

Confounded Carries

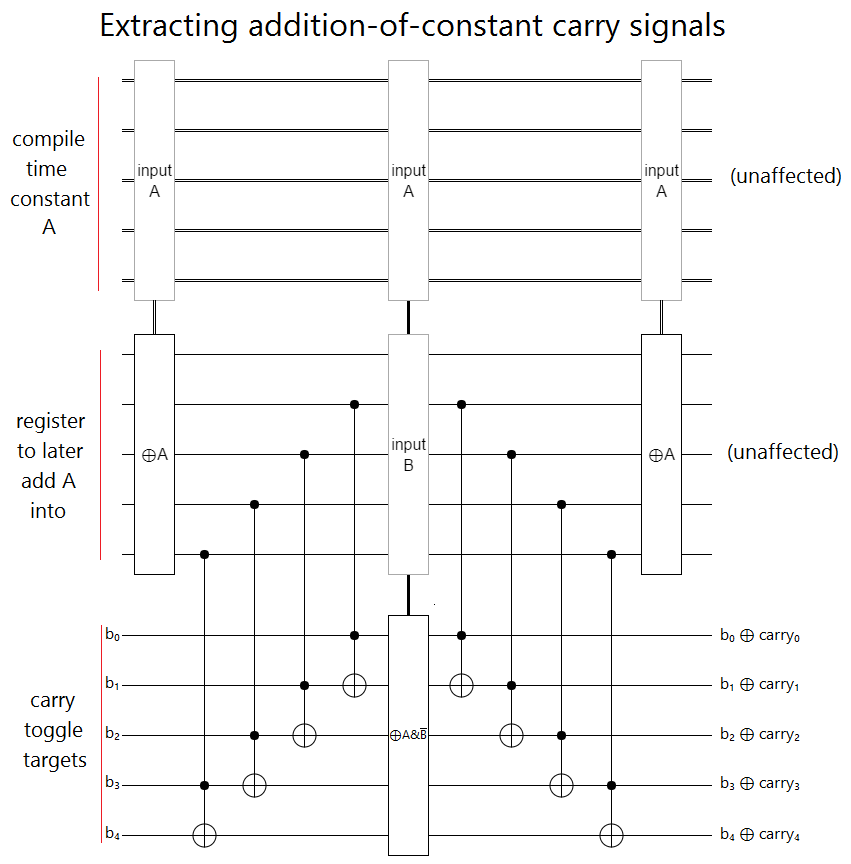

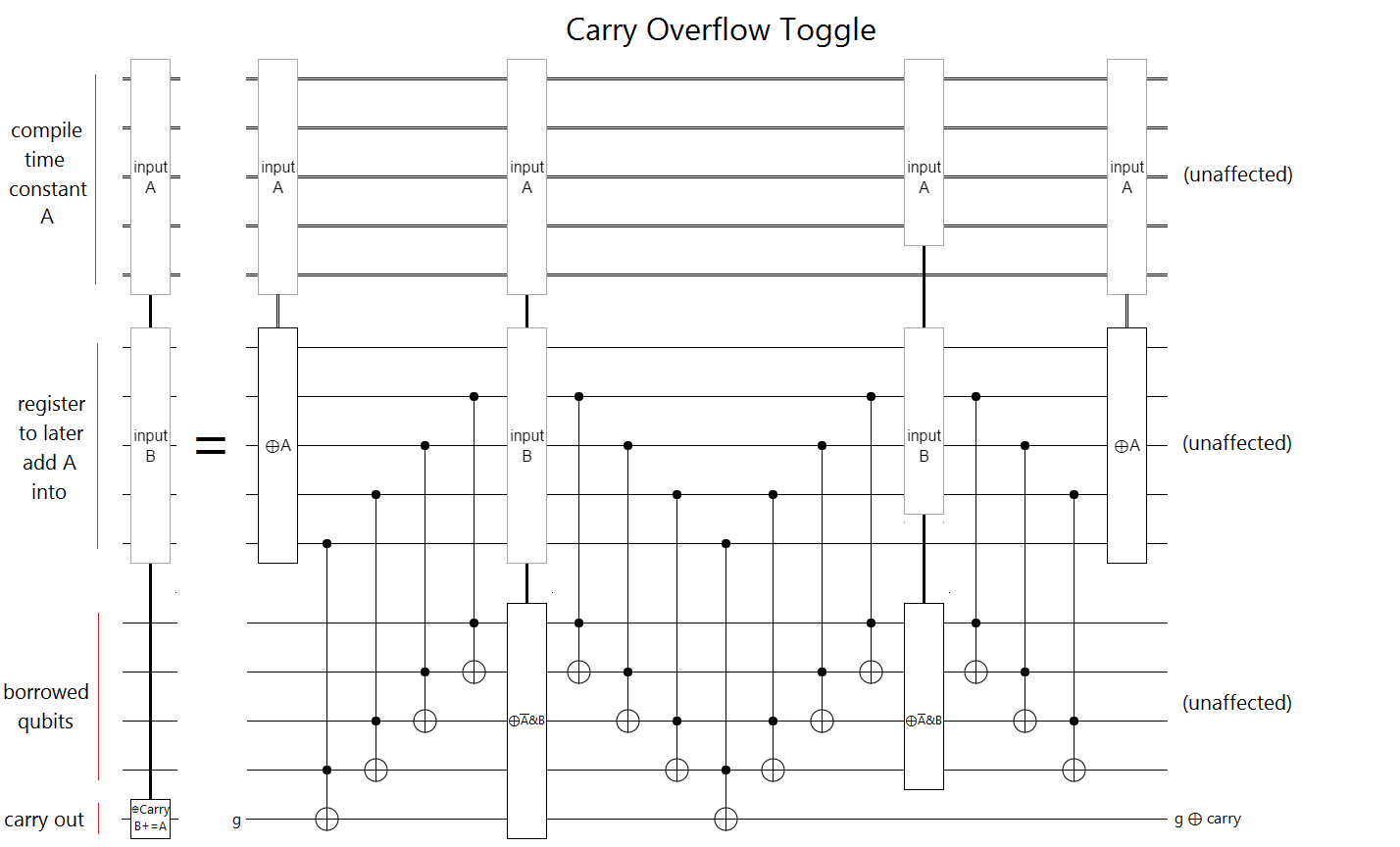

In their paper, Häner et al explain how to cut a constant-addition in half by extracting carry signals. They provide a circuit construction that "pretends" to add the constant into the target, while toggling some other register at the appropriate bit position whenever a carry would have occurred:

This is a clever circuit, but it's also amazingly frustrating. If we could just toggle the actual target register, instead of some garbage register, we'd be done! So I banged my head against it all weekend, and got nowhere.

If you try to have the garbage register kick the toggle back into the actual target register, the setup operations you have to do will change the carry signals.

If you try to do toggle-forwarding, it looks good:

But then there's an exponential explosion. Unpacking the above shorthand into a proper circuit requires factoring the controlled operations into toggle-controlled parts. You want to replace the controlled operation $M$ with pieces $U_k$ such that $\Pi_k U_k = I$ but $\left(\Pi_k U_k X_{\text{carry_toggle}}\right) X_{\text{carry_toggle}} = M$. But factoring the 2-bit increment gate in this way requires more than two pieces, and if you need more than two pieces then the $k$'th step requires running the $k-1$'th toggle twice, which means running the $k-2$'nd step four times, which means... yeah, no good.

I tried a few other things. I found that if you add some garbage register $B$ and then $B \oplus K$ into the target, where $K$ is the value you want to add, you end up adding $K + (\neg B \& K)$. Because the error term has the bitwise-and, you only expect 25% of the bits to be wrong instead of 50%. But there doesn't seem to be an obvious way to continue that line of thought. I also did some algebraic toying with the "carry" operator, finding facts like $\text{carry}(A+K, \neg K) = \neg \text{carry}(A, -1) \oplus \text{carry}(A, K)$, but unfortunately nothing that made the problem any easier.

Häner et al's have a partial solution to the problem, which is to only keep the overflow carry signal and use that to split the problem in half. Keeping only the overflow carry is easy; just uncompute the others:

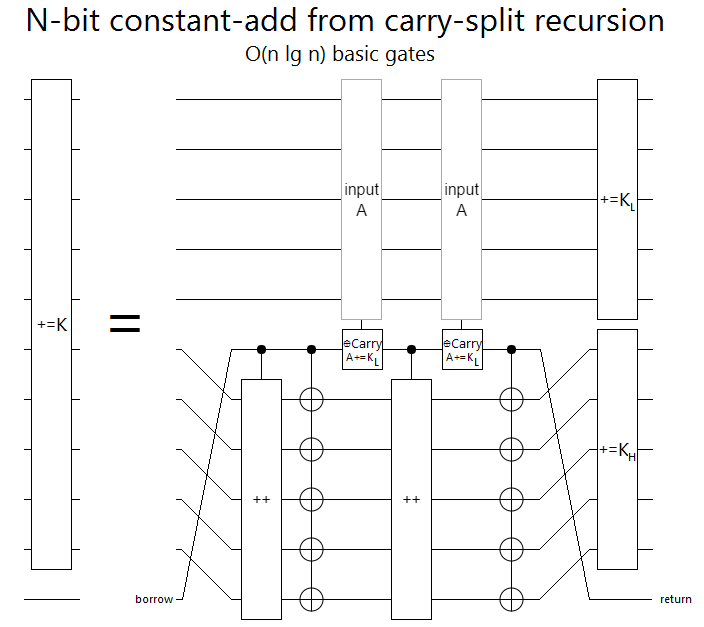

Now, by checking if the bottom half is going to overflow (and borrowing the top half to have space to compute and uncompute the other carries), we can cut the problem in two. The only interaction between the bottom half and the top half is that carry signal. After we conditionally increment the top based on the bottom overflow signal (using the same technique we used when splitting the increments in half), we can separately recurse on two half-sized constant-additions:

Unfortunately, unlike with the other constructions, a follow-up construction that uses the extra available ancilla bits to avoid further recursion is not known. We end up using $F(N) = 2 F(N/2) + O(N) = O(N \lg N)$ basic gates. Not as good as $O(N)$, but reasonable.

(Side note: the path from single large gate to just basic gates, has many many opportunities for optimizations. For example, when doing the carry-overflow within the constant-add-halver, if you borrow bits that aren't the ones being overflowed into then you can use the second call to uncompute the first instead of uncomputing within each one.)

Summary

When ancilla are banned, adding one qubit register into another takes $\Theta(n)$ gates. Despite that, we don't know how to do better than $O(n \lg n)$ gates when adding a compile-time constant into a qubit register. It's an open problem if it can be done with $\Theta(n)$ gates.

My h-index might be 0, but my citations-per-paper ratio is infinite.