Controlled operations are a core part of quantum computation. Not strictly necessary, since any two-qubit gate tends to be sufficient for universal quantum computation, but certainly common.

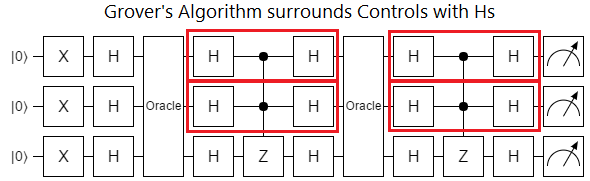

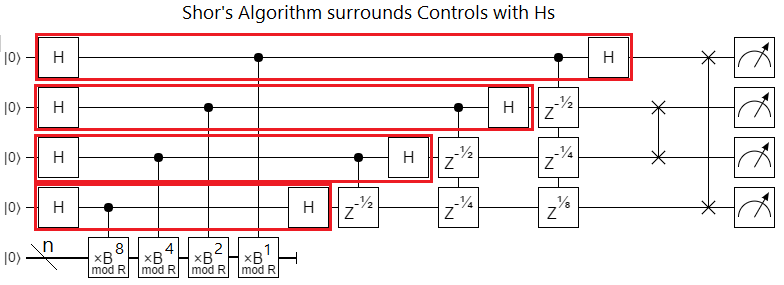

For example, the core of both Grover's and Shor's algorithms are defined by controlled operations. Shor's algorithm uses controlled multiplication operations as part of estimating the period of multiplying-by-a-constant-mod-$R$. And in the case of Grover's algorithm, there's a giant controlled-controlled-...-controlled-Z right in the middle of every step.

As a segway into the meat of this post, I want to point out something common to both these examples: their controls are bracketed by Hadamard gates. The bracketing is blatant in Grover's algorithm, though you may have not noticed it before in Shor's algorithm since the closing Hadamards are typically hidden inside the QFT operation:

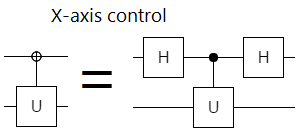

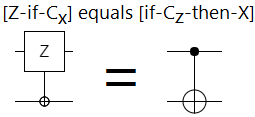

This pattern of control-surrounded-by-Hs is common enough that it's worth packaging it into a single logical thing. I call that thing an "X-axis control". In this post I'll be representing X-axis controls, in diagrams, with a little circled plus:

The reason I call this H-Control-H thing an "X-axis control" is that, instead of conditioning operations on the control qubit being in the state $|1\rangle$, X-axis controls condition operations on the control qubit being in the state $H |1\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt 2} |0\rangle - \frac{1}{\sqrt 2} |1\rangle$ and that state is on the X axis of the Bloch sphere. This makes sense: the Hadamard operation basically swaps the X and Z axes, so bracketing a Z axis control with Hadamards turns it into an X control (and vice versa). Also, as we'll see in a minute, the X-axis control is associated with the X gate in the same way that a normal control is associated with the Z gate.

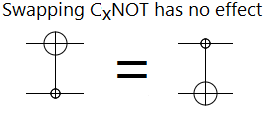

Now, you may be thinking "Hold on, don't we already use a circled plus to represent X gates? Why are we using the same symbol again? Isn't that confusing?". That's a fair complaint. But actually it makes a lot of sense to use the same symbol for both, because X-axis controls are often interchangeable with X gates. If you have an X gate controlled by an X-axis control, you can swap them without changing the applied operation:

(Side note: Because I didn't know the fact diagramed above when I added X-axis controls to Quirk, I picked the wrong symbol for them. Since the matching state has a minus in it, I figured using a circled minus was most natural (and a plus for the inverse control). But the interchangeability with NOT is much more important, so the next version of Quirk will switch conventions and I may go back and fix it in older posts.)

Taking this switch-operation-and-control concept a bit further, note that a controlled-NOT is equivalent to a Z-controlled-by-X:

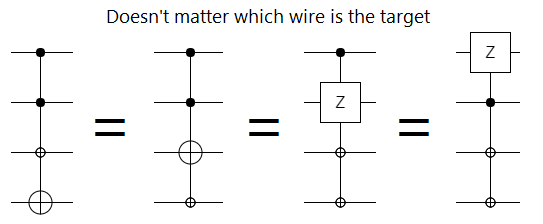

I hope you're starting to get the sense that operations and controls are awfully similar to each other (as long as they have the same axis). In fact, that's correct. In the same way that every rotation has an axis, every single-qubit operation has a corresponding control. We can freely change which qubit is "the target" of an operation, without actually changing that operation, as long as we keep the axes consistent:

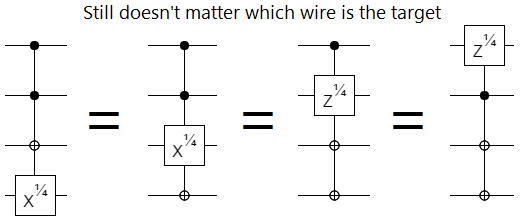

This equivalence between operations and controls even works for partial rotations:

I would go so far as to say that the fact that we distinguish between "operation" and "control", at least in the cases diagramed above, is just a historical accident. A vestigial spandrel inherited from classical computing.

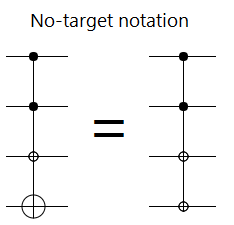

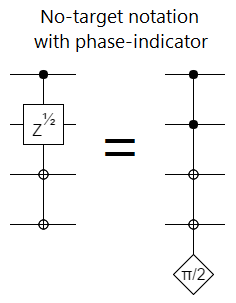

In the context of quantum computing, it often doesn't make to sense to call out any of the wires as "the target" of an operation. Diagrammatically, taking a hint from a common notation for CZs, we drop the whole "target" thing and just use a bunch of linked controls:

For partial rotations, we can use an outside indicator to show how much to phase:

Basically, what we are doing in the above diagrams is describing operations in terms of the eigenvector they affect. Instead of thinking in terms of a specific qubit being turned conditionally, we're thinking in terms of a direction in Hilbert space being negated (or phased). We're thinking in terms of the whole system, instead of in terms of its parts.

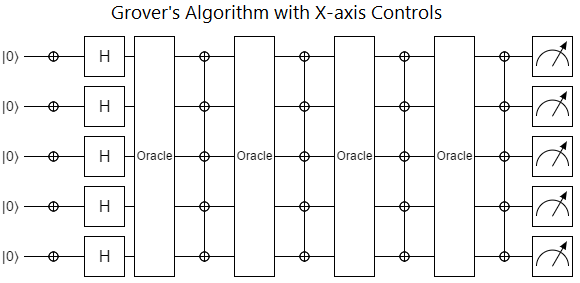

This perspective, of controlled operations as direct specifications of how to phase Hilbert space, is of course a very useful tool-for-intuition when thinking about quantum circuits. For example, the "controls only" approach makes Grover's algorithm simpler in two ways. First, it pushes you to think in terms of overlap between the solution vector and the diffusion vector, which leads to the elegant "rotating towards solution" interpretation of what Grover's algorithm is doing. Second, it makes the circuit a whole lot more compact:

With all that praise of just-think-in-controls done, let's backtrack and go over some reasons calling out individual wires as "the target" is also useful.

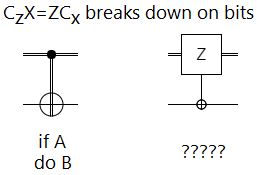

First, whenever we mix classical computation into our quantum computation, it doesn't make a lot of sense to consider the classical bit as anything except a control. You can say "If this bit is ON, then hit that qubit with an X gate.", but it's really weird to say "To the extent that this qubit is in the ON+OFF state, hit that classical bit with a Z gate.". The latter description makes it sound like you'd need to measure the qubit, and that would break the equivalence:

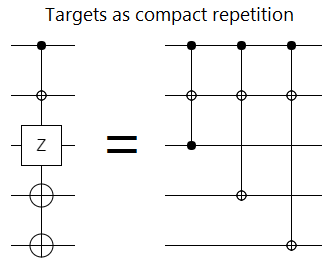

Second, when you have several partially-overlapping operations to apply, marking several wires as a target can be a compact way to represent the set of operations:

Third, we may be controlling larger multi-qubit operations, where the intuitive gains aren't as good.

Note that there is a way to generalize the operation-as-control concept to large operations. Basically, if $|\alpha\rangle$ is an eigenvector of $A$ that gets phased by $x$ degrees, and $|\beta\rangle$ is an eigenvector of $B$ that gets phased by $y$ degrees, then the combined operation $C = \text{Control}(A, B)$ should phase $|\alpha\rangle \otimes |\beta\rangle$ by the product $\frac{x \cdot y}{180^\circ}$.

The product-of-angles approach matches the behavior of controls in three respects: the global phase of an operation matters, eigenvalues of +1 block effects, and eigenvalues of -1 allow effects. If $A$ doesn't affect $|\alpha\rangle$ (i.e. scales it by 1), then $C$ won't affect $|\alpha\rangle \otimes |v\rangle$ for any $|v\rangle$. If $A$ negates $|\alpha\rangle$, then $C$'s effect on $|\alpha\rangle \otimes |v\rangle$ will match $B$'s effect on $|v\rangle$.

Mathematically, we can define the effect of $\text{Control}$ by using logarithms (always remember to try logarithms):

$$A = \sum_a e^{i \alpha_a} |\alpha_a\rangle \langle \alpha_a |$$

$$B = \sum_b e^{i \beta_b} |\beta_b\rangle \langle \beta_b |$$

$$ \begin{align} C &= \text{Control}(A, B) \\ &= \exp \left( -\frac{i}{\pi} \ln(A) \otimes \ln(B) \right) \\ &= \exp \left( -\frac{i}{\pi} \sum_{a} \left(i \alpha_a |\alpha_a\rangle \langle \alpha_a | \right) \otimes \sum_{b} \left( i \beta_b |\beta_b\rangle \langle \beta_b | \right) \right) \\ &= \exp \left( \sum_{a,b} \frac{i}{\pi} \alpha_a \beta_b |\alpha_a,\beta_b\rangle \langle \alpha_a,\beta_b | \right) \\ &= \sum_{a,b} \exp\left(\frac{i}{\pi} \alpha_a \beta_b \right) |\alpha_a, \beta_b\rangle \langle \alpha_a, \beta_b | \end{align} $$

But I digress, since I haven't found a thing for which the above idea adds clarity.

The core point here is that, when doing quantum computation, it's intuitively useful to see operations and controls as basically interchangeable. Every operation defines a control, and every control defines an operation. There's no inherent reason to stick with the conventions of classical computing, where these concepts are unambiguously distinct.

For example, from the view of single-qubit-operations-as-controls, it's trivial to define what classical computation is. Classical computation is what you get if you can combine Z-axis controls with exactly one X-axis control. (The X-axis control is the NOT in the CC...CNOT.)

Meaning quantum computation is more powerful than classical computation... because quantum computation can apply multiple X-axis controls. (Challenge: based on the fact that Toffoli+Hadamard is universal for quantum computation, prove that support for at-most-two X-axis controls is sufficient. No partial rotations.)