A problem I've been interested in lately is "how do I prove I need some number of T gates for a circuit?". As part of thinking about that, I wanted some way to systematically search through circuit space. But just iterating over all the possible combinations and permutations of gates is extremely inefficient, because many circuits with different gates actually apply the same function. For example, take any circuit and add two identical CNOT gates, one right after the other, into the middle of the circuit. This produces a new circuit that's different, but functionally equivalent to the original.

One way to avoid redundant circuits when searching would be to have a bunch of rules like "if the previous operation is a CNOT, don't add that same CNOT again right now". But the ways that circuits can be equivalent is really quite varied, so a rule-based approach is not enough. A better approach is to have some way to transform a given circuit into a standard form, and then instead of searching over all of circuit space just search over the space of circuits in standard form (i.e. canonicalized circuits).

In this post, I'm going to talk about a way to put circuits that contain H, S, CNOT, and T gates into a standard form. Actually, since the H+S+CNOT gate set covers the space of stabilizer circuits, this is a way a way to canonicalize any stabilizer circuit that doesn't do any measurements but does have T gates (which aren't stabilizer gates) sprinkled throughout. Leaving out measurement is kind of a big deal, since constructions that use the minimum number of T gates often use measurement, but for this post we'll focus on the simpler case without it.

Transporting Ts

The key thing we need to do, in order to canonicalize our circuit, is to separate the non-stabilizer operations (the T gates) from the stabilizer operations (the H, S, and CNOT gates). If we can do that, we can handle the T gates on our own and use existing work to canonicalize the stabilizer part (e.g. Scott Aaronson provides a canonical form for stabilizers in "Improved Simulation of Stabilizer Circuits").

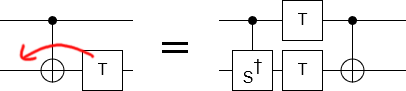

Getting the T gates out is just a matter of moving them to the left. Problem is, there's all these operations in the way causing complications. If you haphazardly move a T gate over the target of a CNOT gate, correcting the phase kickback requires adding a T gate and (more seriously) a non-stabilizer gate that isn't in our gate set (a controlled-S):

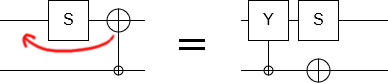

Lucky for us, there's an easy way to avoid this problem: move the T gate downward. That is to say, use proxy phasing to perform the T gate on an ancilla instead of on a qubit in the middle of the circuit:

The benefit of doing this is that, now, the part we need to move over other gates is a CNOT and CNOTs are stabilizer operations. When we move a CNOT over other stabilizer operations, the fixup operations we have to add to restore the circuit's function will be other stabilizer operations.

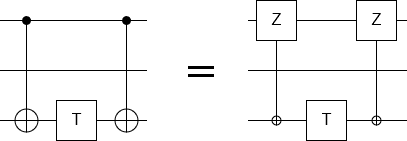

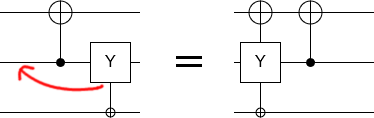

Actually, in order to make things conceptually simpler, it will help to reverse how we think about the CNOT. Instead of thinking of the original qubit (the one the T gate used to be on) as a Z-axis control determining whether an X-axis operation happens to the ancilla qubit, we'll think of the ancilla qubit as being an X-axis control determining whether a Z-axis operation happens to the original qubit:

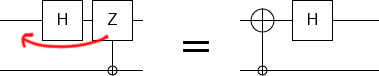

Now consider what happens when we move a Z gate over, say, an H gate. The H gate swaps the X and Z axes, so the rotation axis of the Z gate gets switched from the Z axis to the X axis. In other words, it becomes an X gate. This transformation occurs even if the Z gate is controlled:

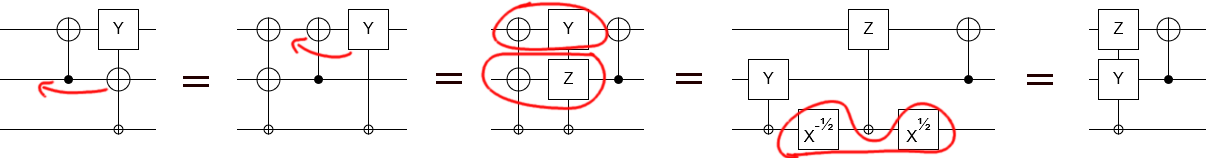

If we had passed the Z gate over an S gate instead of an H gate, nothing would have happened (because they both rotate around the Z axis). But if we pass our X gate over an S gate, it gets changed into a Y gate. Actually, that's not quite right: it gets changed into a minus Y gate. In order to cancel the minus, we kickback a gate out of our control. Since our control is an X-axis control, the kickback operation is an X gate:

In general, the single-qubit operations we pass over will either do nothing to our controlled operation, or switch the axis it operates on, and/or kickback an X gate onto the ancilla qubit. Ultimately, single qubit operations are pretty easy to cross.

Crossing two-qubit operations introduces new complications. When we cross a two-qubit operation, we may get a kickback operation on the other qubit involved in the two-qubit operation. Furthermore, this kickback operation will be controlled by the ancilla qubit. We end up with an ancilla qubit controlling two operations instead of one:

This effect can spread until we're controlling operations on every single qubit in the circuit. But that's as far as it can go. If we end up with two controlled Paulis targeting the same qubit, we can combine them into a single operation. Note that this can cause kickback onto the ancilla qubit (e.g. because $XY = iZ$ instead of just $Z$). Because the kickback phase is $i$ instead of $-1$, the kickback will be an $\sqrt{X}$ gate instead of a whole X gate. That would be a problem, except it turns out that these $\sqrt{X}$ kickbacks always come in pairs that either cancel or combine into a whole X gate. They only happen when crossing two-qubit operation with an anti-commuting Pauli on each relevant qubit:

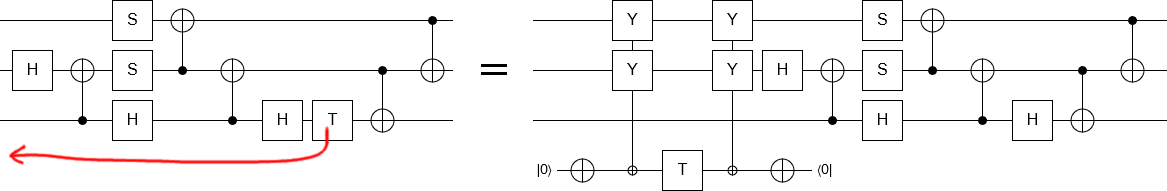

We've now covered all the relevant cases. We just have to take things one gate at a time, pushing each controlled operation further and further left, until we reach the start of the circuit. We'll be left with a "Pauli string" of gates on the qubits, and some kicked-back X gates on the ancilla qubit that combine together to form a single X gate or the identity gate.

Once the CNOT has been moved to the start of the circuit, we can slide the T gate leftward to meet it. We also have to move the other CNOT, but because it will pass through exactly the same operations as the first CNOT it will end up with an identical Pauli string and X kickback. So we can just copy-paste the one we already moved.

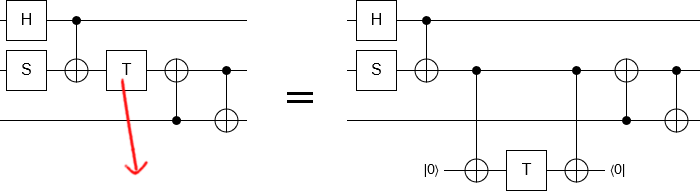

All in all, extracting a T looks something like this:

We simply repeat the T-extraction process for each T gate in the circuit, from earliest to latest. The result is a circuit that starts by applying T gates to several Pauli strings, and finishes with a stabilizer transformation (without measurement). That's our standard form.

Note that the ancilla qubit we introduced and still have at the end of the transformation into the standard form is not strictly necessary. It's possible to migrate the T gate from the ancilla qubit to one of the qubits being targeted by a controlled operation. But this would introduce an unnecessary degree of freedom (i.e. which wire the T gate is placed on), and we prefer standard forms to not have unnecessary degrees of freedom. So we'll ignore this optimization.

Counting circuits

After we've canonicalized a circuit, it has two parts: the T-applying head, and the stabilizer-applying tail. The effect of each T gate in the head is determined by which controlled Pauli operation they apply to each qubit, and whether they have X kickbacks. There are four possible Pauli operations (I, X, Y, and Z) and two possible kickbacks (I and X). So each T gate has $2 \cdot 4^n$ possibilities, where $n$ is the number of qubits. If we have $t$ T gates, and $n$ qubits, there are $(2 \cdot 4^n)^t$ possible circuit heads.

Bounding the size of the circuit tail is a bit more complicated. Instead of working it out, we're just going to look up how many distinct stabilizer operations there are for $n$ qubits. Turns out it's $\Pi_{k=1}^n 2 \cdot 4^k \cdot (4^k - 1)$. That's a pretty complicated expression, so we'll work with the approximation $\frac{2}{3} 2^{2 n^2 + 3 n}$ instead.

By combining the number of possible heads and the number of possible tails, we find that there are $\frac{2}{3} 2^{2 n^2 + 3 n} 2^t \cdot 4^{nt}$ standard circuits with $n$ qubits and $t$ T gates. For scale, note that exploring all 6-qubit circuits that use 3 T gates would involve looking over roughly $10^{39}$ possibilities. Which is an insanely high number. Even if we had some way of solving for the stabilizer part, which sounds pretty reasonable actually, the T part still has ten billion cases.

... I guess that's why people don't find T-count-optimal quantum circuits of any reasonable size using brute force searches.

Summary

It's possible to move T gates across measurement-less stabilizer circuits, without introducing any new operations that aren't stabilizer operations. This allows us to canonicalize stabilizer+T circuits into a standard form that can be searched more efficiently than the full space of circuits. Unfortunately, the reduced space is still gigantic and intractable to search beyond a handful of T gates. (Also, measurement is an important resource when optimizing T count.)

If you're interesting in proving lower bounds on T counts in a slightly more tractable way, check out the Robustness of Magic approach explained in "Application of a resource theory for magic states to fault-tolerant quantum computing" by Mark Howard and Earl T. Campbell.