This is a followup to a post from last year, about the pre-print 'A linear time quantum algorithm for 3SAT' by Zachary B. Walters.

In that post, I argued that the algorithm doesn't do any quantum work. In the comments, Walters and I went back-and-forth. Since then, Walters has updated the paper three times. I suppose it's time to revisit.

After reading the updated paper, I have the same objections as before:

- This is actually a classical algorithm in disguise.

- It runs in exponential time, not linear time.

This time, I'll argue my point by simulating the algorithm with Microsoft's LIQUi|> library.

Walters' Algorithm

Before I jump into simulating the algorithm, I need to explain what the algorithm actually does. Basically, it's a quantum version of the idea "if a clause isn't satisfied, perturb that clause's variables".

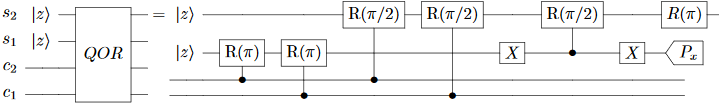

The paper defines the relevant gates in Section 4. First, the paper defines a "QOR" gate (note: the "R" gates are rotating around the Y axis):

This is supposed to set $s_2$ to $c_1 \lor c_2$, and it does. The problem is $s_1$, which ends up containing the parity of $c_1$ vs $c_2$. The paper recognizes that this is a problem (it will cause unwanted decoherence) but claims that measuring $s_1$ along the X axis can fix the problem. That's simply wrong. The correct fix is to uncompute $s_1$, or avoid creating it in the first place via a doubly-controlled operation.

The paper doubles down on the how-erasure-works misconception when defining the "3OR" gate:

This gate initializes $s_4$ to $c_1 \lor c_2 \lor c_3$, but in the process it exposes $c_1 \oplus c_2$, $c_1 \lor c_2$, and $(c_1 \lor c_2) \oplus c_3$ to the environment via $s_1$, $s_2$, and $s_3$. This is enough to reconstruct all three inputs, so all the qubits are decohered after this gate is applied. Once again the correct fix would be to uncompute or to use multi-controlled gates.

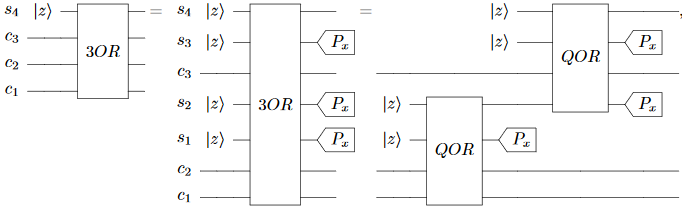

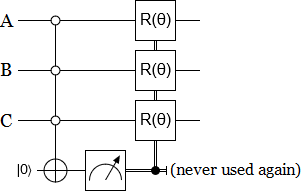

Finally we get to the pièce de résistance, the awesomely-named DECIMATION gate:

The idea behind this gate is that, when $c_1$ and $c_2$ and $c_3$ fail to meet a clause, they get rotated a bit.

Note that this circuit has yet another attempt to destroy indestructible information by measuring it along a different axis. But this time we can't fix it by adding more controls or by uncomputing, because the values we need to do that no longer commute with the values we have. This is the first major flaw in the paper, I think.

Walters claims that measuring the scratch qubit along a perpendicular axis will fix the problem, and he's simply wrong. However... some phrasing in the paper indicates that the decoherence is actually... desired? The paper often talks about "incoherently transferring" states, for example. So it's hard to say if this is a flaw-in-intent or flaw-in-execution or a flaw-in-explanation or what.

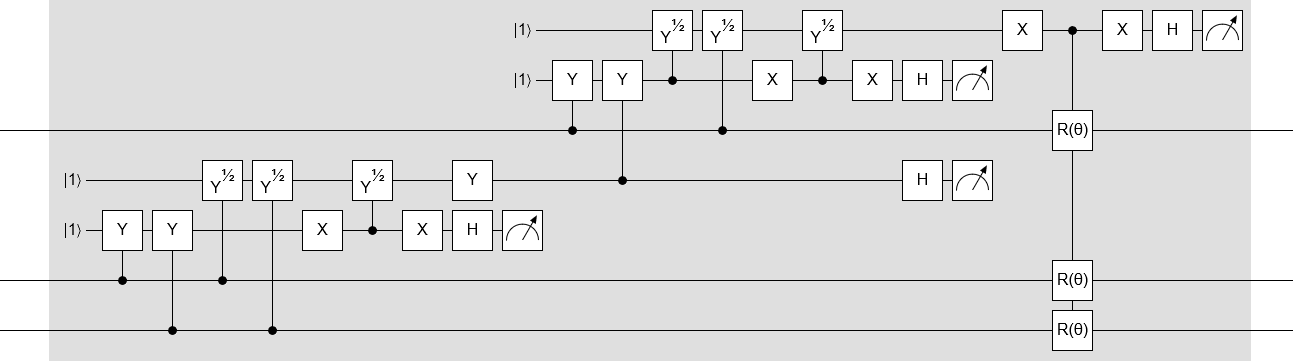

Anyways... here's the whole DE̡͊͠͝CIMATION circuit, expanded in full:

Note that this circuit is specifically for true-or-true-or-true clauses. You have to temporarily invert the inputs to adapt it to other clauses.

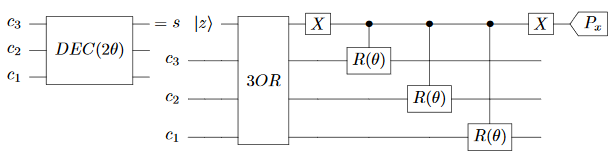

The above circuit is kind of daunting. But if you actually pay attention to how the paper describes the operation, and what it's supposed to do, a much simpler DE̡͊͠͝Cͮ̂҉̯͈͕̹̘̱IM̯͍̭̐̚ATIO̘̝̙ͨ̃ͤ͂̾̆N circuit suggests itself:

Note that this circuit isn't strictly equivalent to Walters' DE̡͊͠͝Cͮ̂҉̯͈͕̹̘̱I̶̷̧̨̱̹̭̯̙̲̝͖ͧ̾ͬͭ̏ͥͮͮ͟͏̮̪̝͍M̯͍̭̐̚AT̴̨̟̟͙̞̥̫͎̭̑ͩ͌ͯ̿̔̀͝ͅIO̘̝̙ͨ̃ͤ͂̾̆N circuit. It causes a lot less decoherence, for example. Regardless, I think it's much closer to the paper's description of what the gate should do than the circuit that's actually included in the paper.

Because I think this shorter circuit better represents the intent of the paper, I'm torn between whether or not I should use it or the actual circuit from the paper when simulating. On the one hand, any changes I make could be pointed to as the reason the algorithm doesn't work. On the other hand, there's so many gates in Walters' construction that I'm more worried about misplacing one than I am about misinterpreting the intent of the algorithm.

What I'm going to do is compromise a bit. I'm going to use my shorter circuit, but tweaked to do the wrong-axis erasure thing even though I think it's pointless.

Simulation Strategy

My simulation code is available on github, in the repository Strilanc/NP-vs-Quantum-Simulation-Walters-Algorithm.

Generally, the simplest way to show that a 3-SAT algorithm takes exponential time is to just find a problem instance it does poorly on. I think that Walters' algorithm is equivalent to the classical algorithm where you randomly toggle variables in clauses that aren't satisfied, so that's the algorithm I used when looking for difficulties. After some experimentation, I found that there are three basic tricks to making a hard instance:

- Use clauses where only one of the three variables is correct, so that toggling tends to hurt twice as much as it helps.

- Make long chains, where variable N doesn't feel any toggle pressure until variable N-1 is correct.

- Include a reset mechanism, where one wrong variable tends to cause all variables to go wrong.

Here's the F# code I use to construct hard instances. Note that when I say "hard" I just mean "hard for this algorithm", not hard in general. The generated instances are actually very easy: there's always exactly one trivial solution.

let evil3SatInstance varCount =

let no i = {index = i; target = false}

let YA i = {index = i; target = true}

// Seeding. First three variables must be false.

let seed = [

Clause(no 0, YA 1, YA 2);

Clause(no 0, YA 1, no 2);

Clause(no 0, no 1, YA 2);

Clause(no 0, no 1, no 2);

Clause(YA 0, no 1, no 2);

Clause(YA 0, no 1, YA 2);

Clause(YA 0, YA 1, no 2);

]

// Chaining. A variable must be false if the two before it are false.

let chain =

seq { 0 .. (varCount-4) }

|> Seq.map (fun i -> Clause(YA(i+1), YA(i+2), no(i+3)))

|> List.ofSeq

// Reset mechanism.

// 1. Every variable tends to become true if a,b is broken

// 2. Any true variable tends to break a,b

// 3. These tendencies are statistically stronger than the tendency to fix any one breakage

let reset =

seq { 0 .. (varCount-4) }

|> Seq.map (fun i ->

[

Clause(no(0), no(1), YA(i+3));

Clause(no(0), YA(1), YA(i+3));

Clause(YA(0), no(1), YA(i+3));

])

|> Seq.concat

|> List.ofSeq

List.concat [seed; chain; reset]

And here's the 27 clauses that make up the 8-variable problem I'll actually be testing on:

!a or b or c

!a or b or !c

!a or !b or c

!a or !b or !c

a or !b or !c

a or !b or c

a or b or !c

b or c or !d

c or d or !e

d or e or !f

e or f or !g

f or g or !h

!a or !b or d

!a or b or d

a or !b or d

!a or !b or e

!a or b or e

a or !b or e

!a or !b or f

!a or b or f

a or !b or f

!a or !b or g

!a or b or g

a or !b or g

!a or !b or h

!a or b or h

a or !b or h

(Originally I planned to do a 16 variable problem, but the simulation was a couple order of magnitudes slower than I expected ahead of time so I dropped back to 8.)

Finally, here's my implementation of Walters' algorithm:

// Perturb-if-not-satisfied-er.

let decimate (power1:int) (power2:int) (qs:Qubits) (Clause(A, B, C)) =

let CCCNot = Operations.Cgate Operations.CCNOT

let CPerturb = Operations.Cgate (fun reg ->

// Turn the Z^(2^-power1 + 2^-power2) gate into an X rotation via surrounding Hadamards

Operations.H reg

Operations.R -power1 reg

Operations.R -power2 reg

Operations.H reg)

let scratch = qs.[qs.Length-1]

let qA = qs.[A.index]

let qB = qs.[B.index]

let qC = qs.[C.index]

// '3-OR' the three variables into the scratch qubit

if A.target then Operations.X [qA]

if B.target then Operations.X [qB]

if C.target then Operations.X [qC]

CCCNot [qA; qB; qC; scratch]

if A.target then Operations.X [qA]

if B.target then Operations.X [qB]

if C.target then Operations.X [qC]

// When clause isn't sarget = b perturb the involved qubits

CPerturb [scratch; qA]

CPerturb [scratch; qB]

CPerturb [scratch; qC]

// Discard the scratch qubit

Operations.H [scratch] // <-- not necessary

Operations.M [scratch] // <-- could be done right after the CCCNot

Operations.Reset Bit.Zero [scratch]

// Iterated per-clause perturb-if-not-satisfied-er.

let waltersDecimationAlgorithm clauses steps (vars:Qubits) =

// Init into uniform superposition of all assignments (skipping scratch bit).

for var in vars.[0..vars.Length-2] do

Operations.H [var]

// Decimate every clause again and again until we hit the given number of repetitions.

let rand = new Random()

for i in 1..steps do

// The decimation power starts high (90 deg) and scales down slowly over time.

let power1 = -3

for clause in clauses do

let power2 = if rand.NextDouble() < 0.5 then -2 else -3

decimate power1 power2 vars clause

// Debug output.

let probs = String.Join(" ", (vars |> List.map (fun e -> String.Format("{0:0}%", e.Prob1*100.0).PadLeft(4))))

let degs1 = 360.0*(Math.Pow(2.0, float(power1)) + Math.Pow(2.0, float(power1) + float(-1)))

let degs2 = 360.0*(Math.Pow(2.0, float(power1)) + Math.Pow(2.0, float(power1) + float(-2)))

printf "Iter %d, Angles %0.1f vs %0.1f degs, Qubit Probs %s\n" i degs1 degs2 probs

// Measure result.

for var in vars do

Operations.M [var]

Note that I did have to make a few guesses when implementing Walters' algorithm. For example, the paper says to randomly vary the perturbation angle between two values for every clause and that the number of iterations needed should be constant (regardless of problem size). It doesn't give specific angles to use, or say exactly how big "constant" is, so I just picked values myself.

Anyways, enough hedging. Let's try it!

Simulation Results

Here's a recording of a typical run of Walters' algorithm on the 8-qubit problem, stopping after 1000 iterations. Because we're using a simulator, we can see intermediate probabilities. The only valid solution is "all qubits off", so we want all the probability-of-ON columns to be showing 0%.

Watch closely:

I want you to focus on the second column from the right. In particular, notice how it sporadically jumps downward but then gets pulled back to 100%. Eventually, around iteration 900, it makes a big enough jump to escape and reach the solution state.

If Walters is right when he claims that the algorithm should quickly decay to a satisfying solution, what keeps pulling that qubit back to 100%-ON? The paper describes the algorithm as a sort of gentle flow through the graph of states, accumulating at the solution. From that you would expect the probabilities to gradually transition from 50% to the target values, possibly with a few detours, as wrong states lose amplitude. But the simulation shows that actually the state is being jerked around and tossed into the later-qubits-are-mostly-ON bin again and again.

When I run the classical variant of this algorithm, where you store a single state and randomly toggle variables in unsatisfied clauses, the same behavior shows up. The system gets stuck in states where the later variables are almost always true, and the reset mechanism keeps breaking the gradual chaining towards a solution. The 'jumps' are just chains that made it unusually far before being reset.

Both the classical algorithm and Walters' algorithm take, typically, a couple thousand steps to solve the 8 variable instance. Sometimes they get lucky and solve it in a hundred, sometimes they get unlucky and the iterations-used-to-solve count spikes to ten thousand, but "a thousand" is a good order of magnitude description. (Note that this is worse than random guessing, because $1000 > 2^8$.)

Based on that high-level view of the behavior over time, and the stopping times being similar, and the obvious decoherence mechanism, my conclusion is that Walters' algorithm is essentially equivalent to the classical algorithm. Secondarily, simulation of different sized problems has made it clear to me that the classical algorithm and Walters' algorithm will take exponential time to solve larger and larger instances of the family of 3SAT problems defined in this post.

Advice

I'm not sure if this post will convince Walters or not, but I can at least give feedback that applies regardless.

First, dump section 4 from the paper. Just use standard circuit constructions instead of defining your own. Feel free to steal my simplified circuit.

Second, drop the "axis of truth" stuff. The success of an algorithm can't depend on what you do to discarded qubits. It trivially violates the no-communication theorem. This is a serious mistake to have in the paper.

Third, do your own simulations. They're an excellent way to convince people that something works and to find mistakes.

Comments

Decimation: to reduce a population by a fixed amount. Etymology arises from a Roman punishment for mutinous legions.

Nonselective Quantum Measurement: performs a measurement on a quantum system without retaining the measured value. The system becomes entangled with the state of the surrounding environment. Tracing over the states of the environment yields the reduced density matrix for the system alone. For an excellent resource on decoherence, see Decoherence and the Quantum to Classical Transition, by Maximilian Schlosshauer. Nonselective quantum measurement is quite well known and well studied, and there are many people who would be surprised to learn that they can't do something they have been doing for their entire professional lives.

Schoening Algorithm: classical algorithm in which the state of a variable in a failed 3SAT clause is randomly toggled. Distinct from the current algorithm in that *all* probability is transferred to a single such state, rather than a fraction of total probability being transferred to *each* such state.

Thus, if TTT fails the clause, the Schoening Algorithm changes the state to TTF, TFT, or FTT. The algorithm under discussion transfers some probability to each of these states, so that TTT becomes, say, 70% TTT, 10% TTF, 10% TFT, and 10% FTT.

Notice that measuring the states of the bits after applying a decimation gate nearly duplicates the Schoening algorithm (the duplication becomes exact if we repeatedly apply the decimation gate + measurement procedure until one variable is flipped). In this case, the decimation gate becomes an expensive random number generator. However, as always, measuring a quantum system has physical consequences. The quantum algorithm sends probability along all possible paths -- a highly parallel breadth first search for the solution state. (Parallel because the system is in an (incoherent) superposition of many states at once, and all states failing a particular clause are decimated.) The classical algorithm chooses one path at random -- a randomized, sequential, depth first search for a solution state.

Despite the superficial similarity, there is no reason to expect a sequential depth first search and a parallel breadth first search to converge in similar times. The quantum algorithm can not be efficiently simulated on a classical computer, because each pass decimating the clauses in the problem requires the probabilities of 2^N states to be updated.

Return Advice:

1) Quantum physics has a long and rich history, and you appear to know little of it. Look up terms of art such as "nonselective quantum measurement," and pay attention to every word. "Nonselective" is quite important in this context. The success of an algorithm can't depend on what you do to discarded qubits is a bizarre statement, and indicates that you do not understand this point.

2) In two posts on this subject, you have not yet said the words "density matrix." Learn what this is, learn how it relates to coherent and incoherent processes, and the theory of decoherence. I personally recommend the Schlosshauer book; another good book is Theory of Open Quantum Systems, by Pettrucione and Breuer.

3) Give it a rest on the mockery. There are many decimation algorithms in the world, and I did not invent the terminology. It makes you look quite unprofessional, particularly when you are writing about topics such as quantum measurement where you are out of your depth.

Thanks for the comment. I'll go through your points in reverse order.

> 3) Give it a rest on the mockery. There are many decimation algorithms in the world, and I did not invent the terminology. It makes you look quite unprofessional [...]

The font-play on the word decimation wasn't intended as mocking. I'm sorry if it came off that way. It's a great name for the intended effect of the gate, and I was enjoying it.

> 2) [...] you have not yet said the words "density matrix." Learn what this is [...]

I'm familiar with density matrices.

> 1) Look up [...] "nonselective quantum measurement[".]

In non-selective measurement, the result of measuring the ancilla informs decisions on what to do to the system next. In your algorithm, the measurement result is just dropped on the floor. It's not used to inform future actions. That's what makes it unnecessary.

The unconditional discarding is what brings your claim that the measurement matters into conflict with the no-communication theorem. The lack of unconditional discarding is what makes non-selective measurement powerful.

> [..] The quantum algorithm can not be efficiently simulated on a classical computer, because each pass decimating the clauses in the problem requires the probabilities of 2^N states to be updated.

I really *really* think you should try simulating your algorithm with LIQUID.

Just start with N=2 and work up to N=20. Updating 2^20 values is no sweat for modern computers. LIQUID goes past 30 qubits. Make a plot of the gate cost as you increase the problem size from 2 to 20 or even 30, and put it in your paper.

> [..] The quantum algorithm sends probability along all possible paths [..]

Probabilistic algorithms also send probabilities along many paths. The relevant difference is that, with classical probabilities, we only need to simulate one of the paths in order to sample from the final distribution. This optimization doesn't work for quantum amplitudes because paths can interfere destructively.

However, there are cases when you can apply the "just pick one" optimization to quantum algorithms and still get the right answer. For example, anytime you have a mixed state you can eigendecompose the density matrix and use the eigenvalues as probabilities for picking the associated eigenvectors. This will not skew the simulated samples. This makes measurement much cheaper to simulate than it otherwise would be.

Another case where you can "just pick one" is when a qubit will not be hit by any more recohering operations. For example, if after step 100 a qubit is only going to be used as a control until the end of the algorithm then you can immediately sample-measure the qubit after step 100 instead of keeping it coherent until the end. This is the Deferred Measurement Principle.

Your algorithm's circuit is an example of a circuit amenable to "just pick one" optimization. But only because discarding the measurement results allows the final Hadamard gates on each wire to be dropped.

... I think that covers all the relevant points.

---

I'll close by repeating my request: Please try simulating your algorithm on small cases. Confirm in-silico that removing the Hadamard gates before the discarded measurements decreases how often it succeeds. Confirm that the number of gates scales linearly with the size of the problem. Show me that I'm wrong.

For the record, the algorithm works just fine on this problem. Here's a simple python script that sets up the transfer matrix and finds the eigenvalues/eigenvectors:

**BEGIN EDIT BY CRAIG**

https://gist.github.com/Strilanc/8a9870c04557be4b3dfcda31560c7d91

(Moved code into a gist. Was too large for one comment and intensedebate was mangling the whitespace.)

**END EDIT BY CRAIG**

Using uniform decimation weights of 0.1 for each clause, the largest nonsolution eigenvalue is 0.89. So even before we implement the back and forth iteration, the algorithm converges like gangbusters.

The reason your code is not working is that you are trying to simulate the evolution of a density matrix using a language that does not treat density matrices (not many density matrix constructors are called "Ket", after all). No trace operations, either, which means you can't implement a nonselective measurement.

Note: I edited your comment to link to the code instead of including it inline. If this is a problem, feel free to complain and I will restore it to the three comment structure you submitted (but I don't think I the comment system can properly handle the whitespace).

I'll look over the code.

I looked over the code. You have a serious bug.

First of all, note that the eigendecomposition that you print out reports several eigenvectors equal to 1. This is bad, because there should only be a single solution. Having more than one eigenvalue equal to 1 means there are incorrect assignments that aren't decaying. But this multiplicity is simply due to the bug.

Your `matchitems` function uses the hardcoded indices 0,1,2 instead of the passed-in indices. This causes it to always focus on the first three variables (sort of) and breaks the `tmat_clause` function that's used to build up the transfer matrix. For example, `clause_transfer_matrix(('FFF', [0, 1, 2], 0.1))` should have non-identity elements in the first and third columns but instead the result has non-identity elements in the first and second columns.

After I fixed that bug, the printed eigendecomposition showed only a single eigenvalue equal to 1, which is good, but the highest degenerate eigenvalue is now ~0.999 instead of ~0.9. That's consistent with my simulation results, where it took on the order of a thousand iterations to pull out the 8-variable solution.

> The reason your code is not working is that you are trying to simulate the evolution of a density matrix using a language that does not treat density matrices

LIQUID is capable of simulating all the operations used by the circuit in your paper.

I don't know exactly what LIQUID does internally, I haven't read the source code, but I would guess that it simulates processes with mixed outputs (such as measurement) by random sampling. Doing it that way is quadratically faster than tracking the whole density matrix, with the downside being that you can only sample from the output distribution instead of getting the whole final density matrix.

Oh, ok, good. I was actually expecting the largest decaying eigenvalue to be close to 1, and I was surprised it didn't turn out that way. Because now we've reached Section 7.1: The Quasiequilibrium Eigendistribution.

The Perron-Frobenius theorem tells us that there is precisely one slowly decaying eigendistribution. The population distribution for the nonsolution states is the same as we'd get if we removed all the solution states from the problem and solved for the equilibrium distribution -- hence "quasiequilibrium." That seems like a stumbling block, until you realize that the quasiequilibrium distribution depends parametrically on the decimation weights. So if you change the decimation angles, you get a new quasiequilibrium distribution and project the old distribution onto the new set of eigenvectors.

Section 7.2: Back and Forth Iteration shows that you can guarantee a minimum population loss by randomly changing the decimation weights, then changing back again, and I give a worked example in the appendix.

Regarding LIQUID: Microsoft calls the object you are working on a ket because it is a ket. It is a rank one tensor. A density matrix is a rank two tensor. They're not the same thing.

I am not sampling any random outcomes, I am tracing over them. That means summing over both outcomes, weighted by the probability of each. If you trace over two bits, you sum over four possible outcomes. If you trace over N bits, you sum over 2^N outcomes. Think of encoding the output of a measurement in the polarization of a photon, then firing the photon out into deep space. The photon is no longer around to be measured, but its polarization is still entangled with the states of the bits in your system, so you trace over all measurement outcomes to yield the reduced density matrix for your system alone. (Note that this means there is information loss, or more properly entanglement between the system and the bits which are traced over: a unitary operation on N+1 bits plus a trace over one bit is in general a nonunitary operation on N bits.)

That reduced density matrix cannot in general be written as the outer product of a ket and its corresponding bra, which is why you need density matrices in the first place. It's an irreversible process, and you cannot describe it in terms of operations on kets. That's why LIQUID doesn't have any trace operators. Their basic data type is the ket, their operators are reversible, and their measurements are selective. It makes sense for what they're doing, but it's not the most general way to describe a quantum system.

In contrast, a selective measurement is when you only keep the density matrix component corresponding to the measured value. That component is by definition an eigenstate of the measurement operator, and any amplitude corresponding to the non measured value is destroyed. If you start from a pure state and perform only unitary operations and selective measurements, you will end up with a pure state.

Here the bits which are being nonselectively measured correspond to the satisfaction of a clause. If you selectively measure these bits, you resolve whether the clause was satisfied or not. If you measure "not," you destroy all amplitude for any solution state, and you have to start over. I do the opposite of this: I use the state of the bit to do a controlled rotation, then I throw away the information it contains by performing a nonselective measurement. See equations 38-41 in the paper.

So there are two fundamental things that we currently disagree about:

1. How much varying the the rotation-when-wrong/toggle-chance-when-wrong parameter increases the decay rate of non-solution states.

2. Whether random sampling between kets is appropriate when simulating circuits that create states described by density matrices.

For (1), I added to your code to compute pairs of transition matrices, multiply them together, and compute the overall decay rate (the largest degenerate eigenvalue):

granularity = 100

weight_choices = [w / 3.00001 / granularity for w in range(1, granularity)]

matrix_choices = [matrix_for_transition_weight(w) for w in weight_choices]

pair_choices = (dot(m1, m2) for m1 in matrix_choices for m2 in matrix_choices)

best_decay_rate = min(decay_rate(p) for p in pair_choices)

print("best decay rate", best_decay_rate, 'adjusted for double application', best_decay_rate**0.5)

The best pair had a decay factor of ~0.992, corresponding to ~0.996 decay per operation. This is supiciously close to 255/256, but I think that's a coincidence (since it depends on the problem definition). The point is that a) alternating parameters didn't help more than just fine-tuning a single weight (also ~0.996), and b) the decay rate is still in the regime of random-guess-check-repeat.

The reason using an alternating pair isn't helping is because all these transition matrices have basically the same slowly-decaying eigenvector. It's as if you were doing a random walk with a wall at p=0 and a cliff at p=n, and a wall-ward stepping bias of 2:1. The chance of taking a step isn't the obstacle preventing you from quickly reaching the cliff, it's the bias away from the goal inherent in each step. Varying the chance of taking a step won't get you to the cliff faster.

For (2), consider that a density matrix can be split into a sum of outer products in multiple ways. As you know, the magic of density matrices is that we don't need to know which split is "the real one". All splits that sum to the same density matrix are observationally indistinguishable.

This is my claim: the different ways of measuring the discarded ancilla qubit correspond exactly to different splits of the same density matrix.

Compute the density matrix you get by tracing out the ancilla. Also compute the density matrix resulting from being told the ancilla was measured along the X axis (you're not told the result, just that the measurement was done). Also the density matrix resulting from being told the qubit was measured along the Z axis. Notice that all three density matrices are equal! They are observationally indistinguishable. And since affecting the success rate of the algorithm would be a distinguishing feature, the indistinguishability implies that how you measure the ancilla can't affect the success rate of the algorithm.

More to the point: we use density matrices to describe what you get when I randomly choose between kets and then give you one. We also use density matrices to describe what you get when I only give you part of a system. Given any density matrix, both approaches can produce states described by that matrix. Since the density matrices are the same, the one produced by random sampling is observationally indistinguishable from the one produced by partial tracing.

Ok, now we're getting down to brass tacks.

The idea behind changing the decimation weights isn't that we will construct a new transfer matrix T2 such that T2=T0.T1 with only large rates of decay. Rather, it's to take care of that residual population that's stuck in the quasistatic eigendistribution of T0.

Remember, I can cause all of the other decaying eigenvectors of T0 to go to zero just by repeating the operation a few times to get (T0)^N. If I do that, my nonsolution probability distribution approaches a constant times v0, the quasistatic eigendistribution for T0. So that's when I change the decimation weights and project v0 onto v1 and w1n, the quasistatic- and quickly decaying eigendistributions for T1. I keep applying T1 for a while, and now my nonsolution distribution approaches a constant times v1. Then I change back to the original weights, projecting v1 onto v0 + w0n.

So if

v0= alpha*v1+ sum_{n} a_n*w1n

and

v1= beta*v0 +sum_{n} b_n * w0n

the quantity that determines the rate of convergence is alpha*beta, the fraction of the population in the slowly decaying space that stays in the slowly decaying space after the back and forth iteration.

So let's modify the code slightly:

#expand a vector in terms of a set of eigenvectors

#eigenvector i corresponds to mat[:,i], so we want to solve ax=b

#where a=transpose(mat) and b=vec

def coeffsolve(mat,vec):

return solve(transpose(mat),vec)

wt=.1

eta=.2

#use uniform weights at first

wts0=ones(len(clausestrings))*wt

#change half of the weights to (1+eta)*wt

wts1=ones(len(clausestrings))*wt

for i in range(int(floor(len(clausestrings)/2))):

wts1[i]*=(1.+eta)

#calculate eigenvalues and eigenvectors for uniform weights

tmat0=tmatrixsetup_clauselist(clausestrings, wts0)

evals0, evecs0=eig(tmat0)

#calculate eigenvectors and eigenvalues for changed weights

tmat1=tmatrixsetup_clauselist(clausestrings, wts1)

evals1, evecs1=eig(tmat1)

#expand quasistatic eigendistribution for T1 in terms of eigenvectors of T0

coeffs0=coeffsolve(evecs0,evecs1[:,1])

#expand quasistatic eigendistribution for T0 in terms of eigenvectors of T1

coeffs1=coeffsolve(evecs1,evecs0[:,1])

residualslowpop=coeffs0[1]*coeffs1[1]

print("slowly decaying component after back and fortht"+str(abs(residualslowpop)))

Which gives a residual slowly decaying population after back and forth iteration of 0.945408369264, which is slightly less than 1-eta^2=0.96.

I don't know if this argument holds for random sampling. In that case, depending on the measurement angle, you can have some off diagonal elements of the density matrix coming into the population transfer, which means you have to treat the evolution of the whole density matrix rather than just the diagonal. But even if you don't mind that, your effective transfer matrix T', where p_new =T'.p gives the new density matrix in terms of the old, now depends on the measurement outcome, which you can't control. So it's much harder to make arguments about decaying eigenvectors. You'd be making some kind of argument about the expected eigenvalues of (T'1.T'2. ...), which is much harder for me to visualize and reason about. I'm not sure the Perron-Frobenius theorem will hold anymore, which is the key property that allows the back and forth iteration to work.

Note that you need to adjust that ~0.945 to take into account the cost of killing off the other eigenvalues if you want to compare it to the ~0.996 from a single step. A typical "second decay" eigenvalue in the problem we're focusing on is 0.8, and it takes 25 hits of 0.8 to get below the noise floor of 1/256. So it would be more appropriate to say the decay rate is ~0.997.

Still, I was surprised the overlap between the two vectors was that low. If it were to stay that low for larger sized problems, and if the second decay eigenvalue also stayed low, then the algorithm would work.

(You realize these transition matrices are stochastic, right? They can be executed by a classical computer.)

I keep going back to the 2:1 random walk as an analogy, and it still applies here. Suppose that, when simulating how the random walk moved probabilities around, we didn't just sweep over the positions and apply each step. Instead, we randomly decide to apply or skip a step at each position.

We'll use two apply-or-skip policies: A and B. Policy A is heavily biased towards applying steps near the wall. For any position closer to the wall than to the cliff, policy A will apply the step at that position 99% of the time. For the other positions it instead skips 99% of the time. Policy B is the opposite: for positions in the cliff half B applies 99% of the time, but for positions in the wall half B applies only 1% of the time.

The transition matrices that represent policy A and policy B have quasi-stable eigenvectors with low overlap, because they both tend to dump slow-moving probability mass in opposite halves. But clearly alternating a bunch of As followed by a bunch of Bs would be a terrible way to push a walker off the cliff faster! In this case the issue is the second decay eigenvalue being terrible, I think.

Yeah, you have to do more steps to achieve the exponential decay -- say, 5N rather than N. But it's still an exponential decay at a rate controlled by a free parameter (eta).

It's not that surprising that the eigenvectors are different. The defining characteristic of the quasistatic eigendistribution is that basically nothing's happening -- for every state, the population coming in is equal to the population going out, minus a tiny amount due to the super slow decay of the eigenvector. So you have

Influx = outgo = population * loss rate = population *( sum_{failed clauses c} wt_{c}) Most of the population is going to get stuck in states that have a low loss rate -- they only fail a clause or two. So when you change wt_{c} to wt_{c}*(1+ eta) for a clause that the state fails, to first order you make up for that by setting population -> population/(1+ eta). So the states where the population changes most are exactly the states where it's concentrated.

For your example, you've got really large changes in the transition probabilities, so my leading order analysis doesn't work as well, although I agree that they should have very little overlap. I guess the way this algorithm asks the question is: given that I am in a stable population distribution now, what is the probability that I am still in a stable distribution after changing the transfer matrix? Not very high, because there's almost no overlap. But for a random walk, you're asking what's the likelihood that my single random path goes over the cliff? Or, I guess, what is the expected number of jumps before I walk off the cliff?

For the quantum algorithm, asking about the distribution is the right question, because we're changing the probability of every state at once with every application of SATDEC. For the walker, the intuitive way to treat it would be as a random walk. But the connection between the two approaches seems very tricky and subtle.