Last week, the paper 'Genetic Algorithms for Digital Quantum Simulations' by U. Las Heras et al. was published in Physical Review Letters.

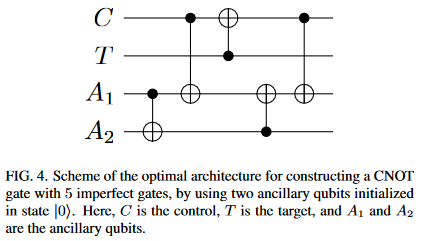

I was reading through the pre-print, when I saw figure 4 and did a double-take:

(Note: Yes, the same diagram is in the published paper)

Look at that diagram. Look at it some more. Savor that initial controlled-not of A1 onto A2. Take in the whole picture.

See anything strange?

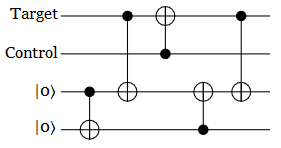

The initial thing that caught my eye was the fact that T is supposed to be the target, but nothing ever toggles T. Apparently the authors accidentally switched the wire labels. An understandable mistake, easily fixed:

The second odd thing is that there's no Hadamard gates. Those are important if you want to detect phase errors.

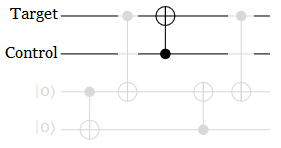

But the really odd thing is the work bits. I mean... what are they even doing? They get toggled, but they never toggle back. You could make this circuit strictly simpler by throwing away every single operation that touches a work bit:

This reduced circuit isn't exactly equivalent to the original when errors are in the mix, but still. What are the extra gates for? Why would this seemingly-bloated circuit score highly on an error metric?

Purpose

After staring at this circuit for too long, trying to fathom what the heck it's supposed to be doing, I have a guess.

I think the authors used an error model based on gate fidelity, where each gate's effect is perturbed slightly. This turns gates into a tradeoff. Every time you apply one, you accumulate some error. But, using error correcting schemes, if the error rate is low enough, it's possible to suppress problems faster than they appear. That's what the authors were hoping to see their GA do.

But evolution doesn't always find the solution you intended. Low fidelity gates are a costly tradeoff... if you apply them to wires that matter. Another strategy, when you're forced to use a fixed number of terrible gates, is to do as much work as possible on useless wires that don't affect the result. Use one gate to do the work you have to do, throw in a connecting gate to satisfy a rule about the work bits being affected by the bits that matter, add another connecting gate to uncompute the first, dump the rest of the awfulness onto bits that don't matter, and you've found yourself a high scoring circuit!

(Note: This 'useless work' strategy is also good if errors are introduced at a constant rate per time step, but independent of the number of wires, so that more wires means fewer errors per wire. The useless work bits would act as chaff, absorbing some of the errors.)

I don't have access to the author's source code, so I can't say for certain that this is what happened. The real reason is probably more complicated, and more subtle. But, from the outside, this really does look like a "do error-prone work on bits that don't matter instead of bits that do" design.

Judgement

The weirdness of this circuit jumps out at you if you look at it for more than a minute. Maybe I'm overlooking something obvious, but the authors and the reviewers really should have noticed. I'm sure the authors verified that the circuit scored highly on their error metric... but currently I think they should have thought some more about why it scored so highly.

The mistakes in this one diagram put every result from the paper into question.

Oh well. At least this will make another good "it did what I said, not what I wanted" anecdote.

(Note: Also, why would you use a GA to search the space of 5-gate circuits? It's small enough to brute force.)