One of the annoying things about the Quantum Fourier transform is that it uses very small phase factors. An exact $n$-qubit QFT requires applying a $Z^{2^{-n}}$ gate.

Of course, in practice you don't need your QFT to be exact. You can use multi-gate constructions that approximate small phase change gates, and past some reasonable cutoff (that depends on your error budget) you can just completely skip the tiny phase changes because they have so little effect on the measured result.

But still, it'd be nice to be able to apply an exact QFT without having to deal with all these finnicky gates every time. In this post, I'm going to explain one way to do that, by using a re-usable gradient resource that can be prepared ahead of time.

Shifting vs Phasing

The Fourier transform converts between the time domain and the frequency domain. One of the consequences of this fact is that, when you shift samples in the time domain, you end up phasing values in the frequency domain. Rotating indices gets turned into rotating values (and vice versa).

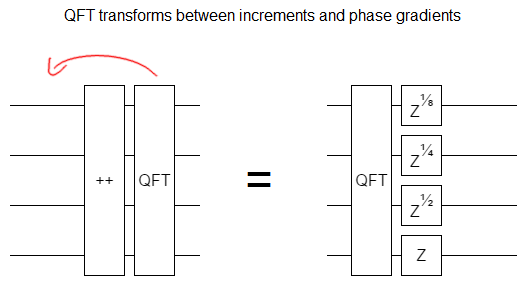

Concretely speaking, this means that you can hop a QFT gate over an increment gate, without changing the function of the circuit, as long as you replace the increment with a phase gradient:

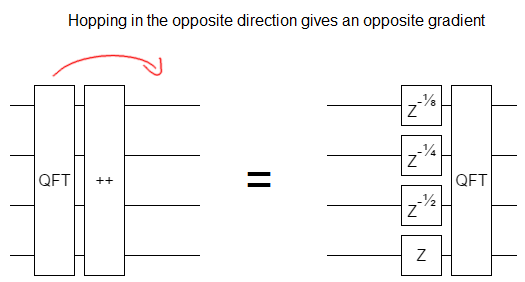

But keep in mind which direction you're hopping! If the QFT gate goes from left to right, instead of from right to left, the gradient is negated:

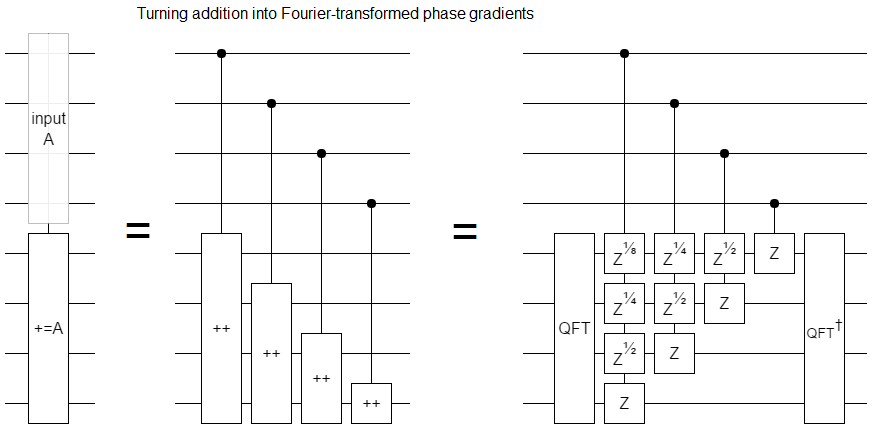

This "increment is fourier-transformed phasing" doesn't just apply to incrementing, it also applies to conditional incrementing. That allows us to also apply this transformation to addition. If you add $a$ into $b$, that's equivalent to Fourier-transforming $b$, applying a controlled phase gradient for each bit of $a$, then un-Fourier-transforming:

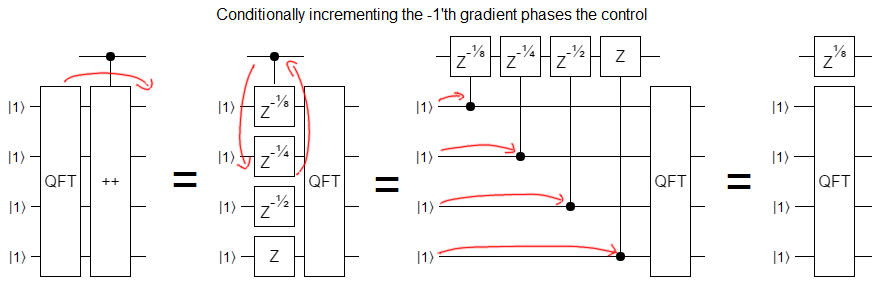

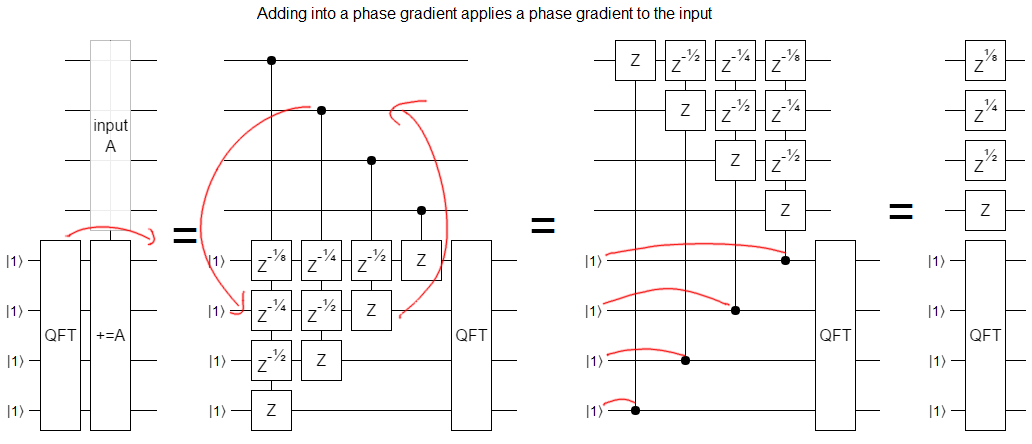

Now lets consider what happens when you increment into a phase gradient. Specifically, the phase gradient you get when you fourier-transform -1. Surprisingly, we end up phasing the control instead of affecting the gradient:

What about addition? Basically the same thing happens. A phase gradient is unaffected when you add $a$ into it... except that $a$ itself gets phased by a gradient!

Applying to the Fourier Transform

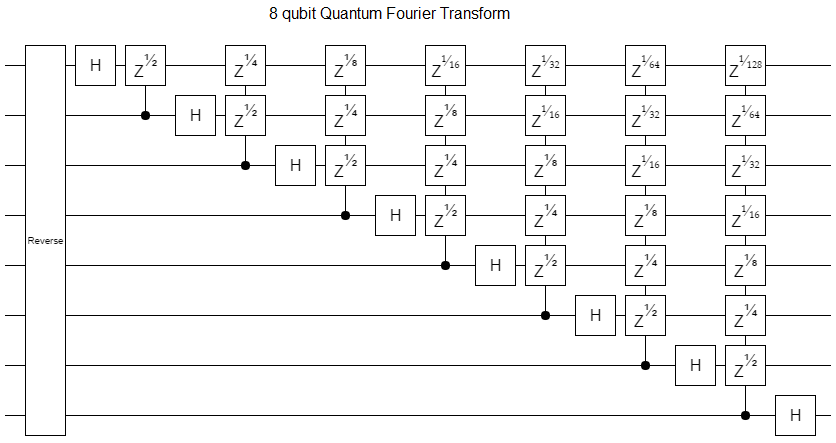

The Fourier transform is basically made of phase gradients:

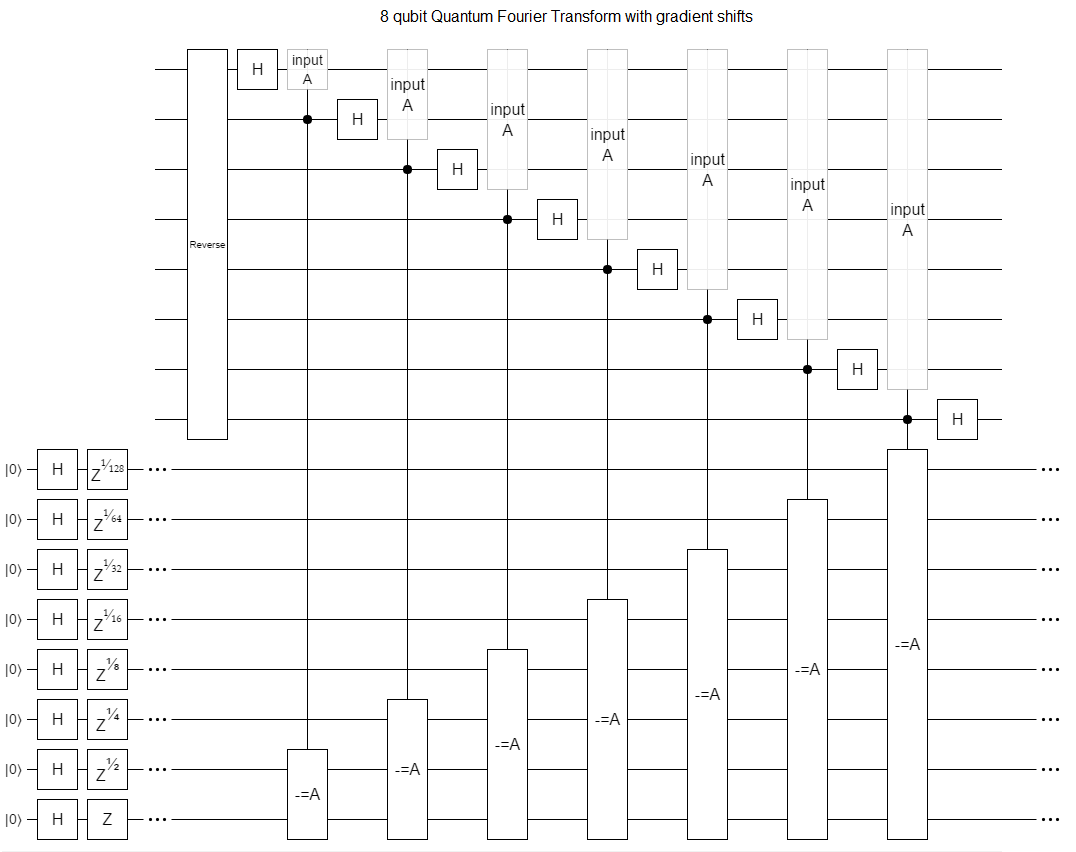

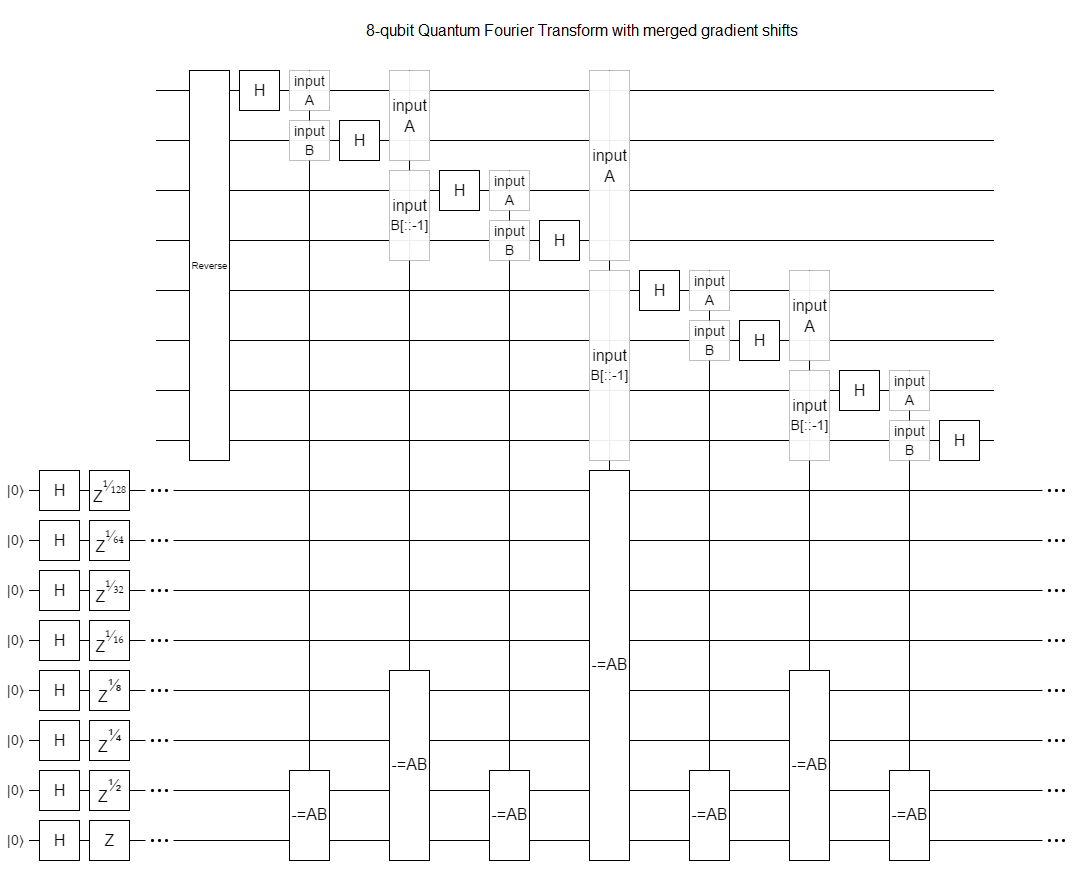

And so, instead of using Z gates to create those gradients, we can use an addition into a pre-existing gradient:

Note: I used subtraction in the diagram, not addition, but it's exactly the same idea.

Why would we do this? Because addition doesn't require arbitrarily precise gates. We can implement it starting with a gate set containing just the Hadamard gate, the controlled-not gate, and the $Z^{1/4}$ gate (also known as the $T$ gate).

By setting up the phase gradient ahead of time, we only need to pay the price of approximating exponentially precise gates once. We can then use that gradient again and again for as many QFTs, inverse QFTs, and various other things-that-need-precise-phase-gates, as we want.

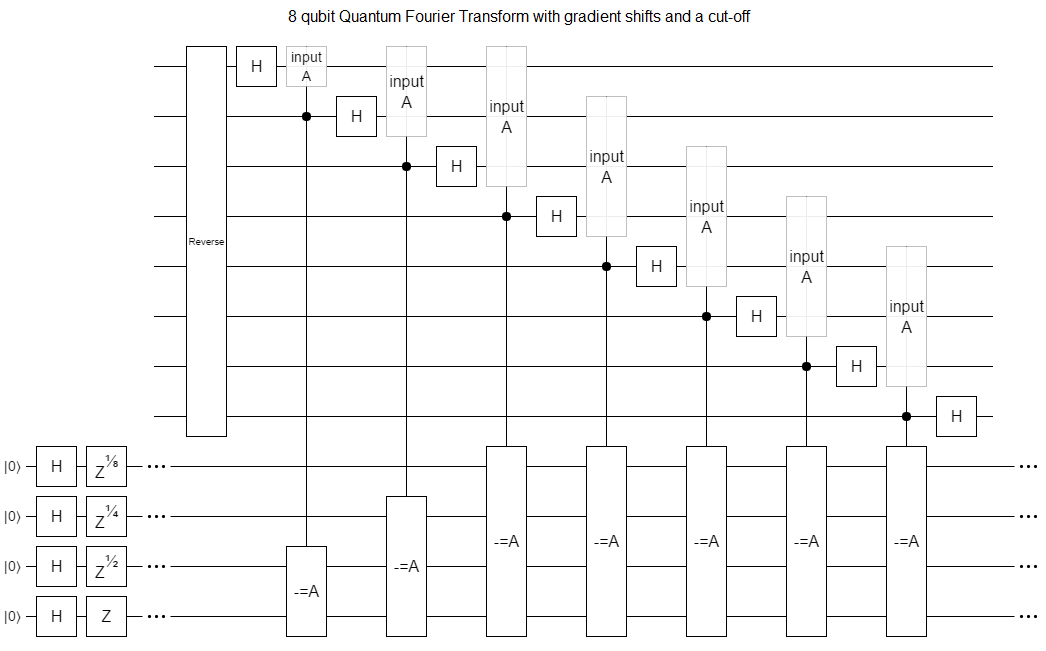

Also, this add-into-gradient approach combines well with using a precision cut-off. Just do smaller additions:

Assuming we need to accumulate at most $\epsilon$ phase error, this approach requires only $O(n \lg \frac{n}{\epsilon})$ gates. That's pretty good!

We can also combine this adding-into-gradients idea with the combine-phases-where-possible-using-multiplication idea that I discussed in another post:

Compared to the linked post, MAC-into-gradient uses half as many multiply-accumulates and reduces the total number of more-precise-than-$T$ phase gates (including preparation) from $O(n \lg n)$ to $O(n)$. That's a big improvement!

(Side note: At first I was hoping that we could recursively apply these improvements to the multiply-accumulates. Fast multiplication algorithms start with a Fourier-transform of the inputs after all, and we're in the middle of doing that already. Alas, it doesn't quite seem to work because the QFT treats the amplitudes as the time-domain samples whereas the multiplication algorithm needs to treat the individual qubits as the samples.)

Polynomial Similarities

Let me mention one last interesting thing.

You may or may not be aware that Fourier transforms can be applied in fields other than the complex numbers. Basically all you need is a big root of -1, and lots of fields and even rings have a big root of -1.

Specifically, you can do a Fourier transform within the space of polynomials modulo $x^n + 1$, where $x^n \equiv -1$ and $x$ is a $2n$'th principal root of unity. If you map what that polynomial FFT is doing into a quantum circuit form, in the same way that the QFT circuit maps what the Cooley-Tukey algorithm is doing into a quantum circuit form, you end up with something that looks exactly like the adding-into-gradients circuit we just made... except that there's no phase gradient preparation at the start. Or, equivalently, the phase gradient has been Fourier transformed into a shift.

So, in a sense, the Fourier transform on negacyclic polynomials is a Fourier-transformed Fourier transform.