When it comes to toying with quantum computing, I think Quirk has pushed the "drag blocks around on a circuit diagram" concept about as far as I want to go. It's great for small problems, but becomes horribly tedious and error-prone as things get more complicated. This is a common problem with very visual approaches to programming. There's just something about text that scales better, once branches and loops and functions come into the picture.

With that in mind, I've been thinking a lot about what I would want out of a quantum scripting language. There are many quantum programming languages / libraries out there already (QCL, Quipper, QuTIP, LIQUi|>, QASM, etc), but I think I want a language with an extreme focus on play. Something that focuses on immediate feedback, fast iteration, and convenience; not a tool for producing highly optimized gate sequences.

So... here's some of the things I've been thinking about. Keeping in mind that I'm definitively not an expert at designing programming languages.

Implicit Uncomputation

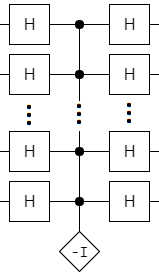

The heart of Grover's search algorithm is the 'diffusion' operation, which 'inverts amplitudes about the mean'. In circuit form it looks like this:

It's quite simple, as far as quantum operations go.

Here is the sample code for this operation from the Quantum Computing Playground (slightly edited):

proc Diffusion

// Hadamard transform the input qubits

for i = 0; i < regwidth; i++

Hadamard i

endfor

// AND all the controls together, using ancilla qubits

Toffoli 0, 1, regwidth

for i = 2; i < regwidth; i++

Toffoli i, regwidth+i-1, regwidth+i

endfor

// Apply the conditional phase factor

Z regwidth+i-1

// Uncompute the 'AND all the controls together'

for i = regwidth-1; i >= 2; i--

Toffoli i, regwidth+i-1, regwidth+i

endfor

Toffoli 0, 1, regwidth

// Un-Hadamard transform the input qubits

for i = 0; i < regwidth; i++

Hadamard i

endfor

endproc

I don't want to give the impression that this is a typical implementation. It's not. It has essentially no abstraction at all. But it does make a good jumping off point. (Cleaner samples: in Quipper, in LIQUi|>, in QCL.)

The first thing making the playground code complicated is the association of qubits with global indices. This makes writing and calling functions incredibly tedious, because you need to carefully consider which slots are available at any given time. Quantum memory should be treated like classical memory: a resource we can allocate, free, and pass around as needed.

Passing in the target qubits, and allocating the needed ancilla qubits, purges most of the opaque index math from the code. Also, we'll switch to a more Pythonesque style:

def diffusion(qubits):

n = len(qubits)

# Hadamard transform the input qubits

for q in qubits:

Hadamard q

# AND all the controls together, using ancilla qubits

ancillas = qalloc(n)

CNOT qubits[0], ancillas[0]

for i = 1; i < n; i++:

Toffoli qubits[i], ancillas[i-1], ancillas[i]

# Apply the conditional phase factor

Z ancilla[n-1]

# Uncompute the 'AND all the controls together'

for i = n-1; i >= 1; i--:

Toffoli qubits[i], ancillas[i-1], ancillas[i]

CNOT qubits[0], ancillas[0]

qfree ancillas

# Un-Hadamard transform the input qubits

for q in qubits:

Hadamard q

Now that we don't need to worry so much about where qubits are, we can start extracting functions out of this one. The 'and all' logic is a clear candidate for that, as is applying the Hadamard transform to an array of qubits.

We immediately run into a problem when extracting the all function: it needs two parts!

One part to return an ancilla qubit containing the result, and another part to uncompute and free that ancilla.

That means two utility methods instead of one:

def diffusion(qubits):

# Hadamard transform the input qubits

Hadamard qubits

ancilla_qubit = compute_all(qubits)

Z ancilla_qubit

uncompute_all(qubits, ancilla_qubit)

# Un-Hadamard transform the input qubits

Hadamard qubits

If you're a C++ programmer, this "create and cleanup" pattern is very familiar.

This is exactly what RAII is great at.

Other languages have analogous constructs for scoped cleanup, such as python's with block.

A with block does seem to help:

def diffusion(qubits):

# Hadamard transform the input qubits

Hadamard qubits

with ancilla_qubit = compute_all(qubits):

Z ancilla_qubit

# Un-Hadamard transform the input qubits

Hadamard qubits

But I don't think with goes far enough.

I think this pattern of "make an ancilla and apply operations that have no effect if the ancilla is off" is going to happen all the time in quantum programs.

So much so that it makes sense to fold the pattern deeply into the language, as a standard part of the if statement.

Instead of a with containing a Z, let's try having an if leading to a phase factor:

def diffusion(qubits):

# Hadamard transform the input qubits

Hadamard qubits

if all(qubits):

phaseby pi

# Un-Hadamard transform the input qubits

Hadamard qubits

The if block is more complicated than it looks.

There's an ancilla qubit coming into existence at the start of the if, that's being used to control all operations within the if, and finally being uncomputed at the end of the if and free'd.

Come to think of it, the Hadamard transforms at the start and end of the function fit this exact compute/uncompute pattern we're trying to handle.

Let's add an x_axis function that applies the Hadamard transform, and tells the scoping mechanism to apply another Hadamard transform when uncomputing:

def diffusion(qubits):

if all(x_axis(qubits)):

phaseby pi

Ah, much nicer!

We can even throw in a phase_flip_if function, if we're feeling particularly bike-shed-ish;

def diffusion(qubits):

phase_flip_if(all(x_axis(qubits)))

I don't think we're going to get any more succinct than that.

Notice that we started with a confusing 13-line function, applied a few abstractions (allocating qubits, extracting common methods, RAII-style uncomputing), and ended up basically the description I gave at the start of this section: negate the part of the superposition where all the qubits are pointing rightward.

It also works well in the context of the whole algorithm:

def grover_search(bit_count, predicate):

qubits = qalloc(bit_count)

apply X to qubits

apply H to qubits

for _ < pi/4 * 2**(bit_count/2):

phase_flip_if(predicate(qubits))

phase_flip_if(all(x_axis(qubits)))

return measure qubits

But there are dark corners to this implicit uncomputation thing. There's quite a lot of magic going on to make sure everything works together in the right way to uncompute the implied ancilla. And the magic ends up being somewhat fragile.

Accidental Decoherence

Recall that the quantum-ized if statement uses the condition expression to compute and uncompute an ancilla qubit used to condition actions.

Consider: what if the action changes the condition?

For example, suppose you write this:

if x_axis(qubit):

apply H to qubit

Which would be compiled down into a sequence of basic operations like this:

# Compute condition for IF

ancilla = qalloc()

apply H to qubit

apply CNOT to qubit, ancilla

apply H to qubit

# Body of IF

apply CH to ancilla, qubit

# Uncompute condition for IF

apply H to qubit

apply CNOT to qubit, ancilla

apply H to qubit

qfree ancilla

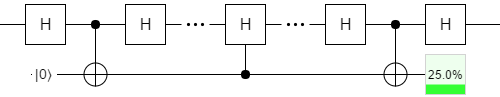

Or, equivalently, this circuit:

Notice that the ancilla wire (the bottom one) isn't OFF at the end of the circuit. The uncomputation step didn't work correctly.

The body of the if changed the value used to compute the condition, and this caused the uncomputation of the condition ancilla to play out differently than the computation of the condition ancilla.

As a result, when the simulator discards the ancilla, it's still entangled with the input qubit.

This is a measurement.

It forces the system to decohere.

I'm a bit worried that this accidental decoherence issue will end up being a huge problem for usability. It's kind of hard to tell whether or not this action-affects-condition problem is present in code. For example, consider this code:

if x_parity(q1, q2) != z_parity(q1, q2):

apply Y to q1

Notice that the code is operating on a qubit (q1) while conditioned on that same qubit.

So you might expect this to break the uncomputation.

But actually the uncomputation will work fine!

This code ends up applying a valid 2-qubit operation defined by the following unitary matrix:

$$\frac{1}{2} \begin{bmatrix}1&i&i&1\\-i&1&-1&i\\-i&-1&1&i\\1&-i&-i&1\end{bmatrix}$$

The reason it works is because the difference between the X-parity and the Z-parity of two qubits is actually just their Y-parity. And since the Y operation rotates around the Y axis, it won't change whether a state is along or against the Y axis. We do affect the X and Z parities, but we affect them in a way that cancels out and so the uncomputation works properly.

The criteria for an implicitly-uncomputing if statement to not cause decoherence is that the action must commute with the condition.

That is to say, given the observable $C$ defined by the condition, the action should never move states across the boundaries of that observable's eigenspaces.

This criteria is somewhat difficult to check, to put it mildly. Even if we had well-defined matrices for the condition and the action, those matrices are huge. Computing their commutator would be way too expensive; it'd easily limit us to 8 qubits. But the real monster here is that the condition and the action are made up of code that can contain function calls and loops and generally anything. They're turing complete. An analyzer that could unambiguously tell you if arbitrarily complicated condition/action pairs might cause accidental decoherence would also be able to solve the halting problem; it's impossible!

Ultimately, all we can reasonably do is have the simulator detect that the ancilla wasn't properly cleared at runtime, and warn the user that they've probably made a mistake.

More Accidental Decoherence

Recall the x-parity-vs-z-parity example from the previous section:

if x_parity(q1, q2) != z_parity(q1, q2):

apply Y to q1

I think it's pretty reasonable for a person to expect the following code to be equivalent to the preceding code:

if not x_parity(q1, q2) and z_parity(q1, q2):

apply Y to q1

elif x_parity(q1, q2) and not z_parity(q1, q2):

apply Y to q1

But they're not! In the second example, the conditions are stricter in a way that doesn't commute with the action being applied. The second example will cause decoherence that's not present in the first example.

Another thing, that initially seemed reasonable to me, was allowing the compiler to hold on to ancilla besides the condition (as a workaround for cases that can lead to an exponential explosion in re-computation/re-uncomputation work).

But those extra ancilla may not commute with the action of the if statement, and so we need to be very careful about keeping them around.

The user can't reasonably be expected to guess whether the compiler will happen to cache information that doesn't commute with the stated action.

Finally, note that this condition-must-commute-with-action stuff means quantumized while loops can't work.

There's just no way to do the uncomputation correctly, because our exit condition implies our "uncomputation dun broke" criteria.

(Also, because I want a classical program counter, and the condition controls the program counter for an indefinite amount of time, it's somewhat inconvenient to keep the condition coherent.

You'd need to apply a fixed number of iterations.)

So I'd say implicit uncomputation seems like it could be really useful, but it could also be a source of many dumb bugs and confusions. Implicit uncomputation is also going to heavily impact how functions are declared and written, since whether or not a function is reversible determines whether it can be used in a quantum condition.

Computed Phases

One of the building-blocks of the quantum Fourier transform is a conditional phase gradient. Here's what the implementation of that might look like, using the ideas so far:

def controlled_phase_gradient(control_qubit, target_qubits):

if control_qubit:

for i < len(targets):

if target_qubits[i]:

phaseby pi / 2 / 2**i

But I don't think this is the most natural way to think about the phase gradient. Contrast it with the Cooley-Tukey FFT algorithm's twiddle angles, which increase linearly with the array index.

I think we should be using the linear indices thing, and rely on the compiler to turn it into the nice column of gates. That lets us write this shorter code:

def controlled_phase_gradient(control_qubit, target_qubits):

if control_qubit:

phaseby qint(target_qubits) * pi / 2**len(target_qubits)

Or even:

def controlled_phase_gradient(control_qubit, target_qubits):

phaseby qint(control_qubit) * qint(target_qubits) * pi / 2**len(target_qubits)

Because the angle expression includes qubits, it ends up phasing by different amounts in different parts of the superposition.

Note that this isn't trivial to compile into a gate sequence, but it's possible. And as long as it's possible, I don't care much about the gate sequence being gross or the gate count being terrible. What I care about is simulation speed. And computed phases will translate into very straightforward and efficient shader code.

Peeking

Quirk's best feature is its inline displays. I definitely want to incorporate the concept of "tell me the state right now, without messing things up" into the language, as a debugging tool.

I'm undecided whether or not I should use the print statement for this purpose. Print debugging is a proud tradition, but in a real quantum computer it would necessarily cause measurements. Should printing act like real life, or should it act convenient?

I do know that I want to have commands like peek qubits that create displays that update whenever the program runs over that statement, but I'm not sure how they should interact with the much higher amount of entanglement that's likely to be present.

For example, in Shor's algorithm the state is expanded from x to x, f(x).

I think a display over just the x value should still show the phases, unlike in Quirk where it would happily show incoherent because of the entanglement with the qubits holding f(x).

But I'm not at all sure exactly what rule will work well in general. Maybe total mutual information?

Other Random Notes

- No installation. Gotta run in web browsers. Needs to make sense when backed by JS and WebGL.

- Optimize design choices for programs between 100 and 1000 lines

- Dynamic types (because downsides don't affect small programs)

- Imperative (because I think it meshes well with the no cloning theorem)

- Simulation speed trumps gate counts

- Peeking is allowed, but can't be conditioned on

- Functions declared as reversible/pure

- Implicit uncomputation

- Automatic ancilla

- Computed phases

- Computed gates

- Built-in arithmetic, including modular arithmetic

- Treating qubits as quints

- Always down-sample density matrices into kets

- Reference counted qubits; decohere when collected

- Translation of chunks into GLSL

I don't really have a conclusion for the post. Peeking would be nice. Computed phases seems kinda obvious; it doesn't even have to be done at the language level. The implicit uncomputation thing seems really interesting, but also like it could be a minefield.

Overall, I'm not sure if I could make something good enough to be worth the time.