One of the first things you notice, when learning quantum things, is people surrounding all their symbols with a strange angular notation. Instead of writing "let $a$ be the state", they keep writing "let $|a\rangle$ be the state". And the natural reaction is: "Why do they do that? It seems completely superfluous!".

In this post, I'll quickly describe bra-ket notation. Then I'll explain why I like it. Namely, because bra-ket notation took something I always considered horribly finnicky and turned it into something trivial.

Bras and Kets

I think of bra-ket notation as being made up of four key concepts from linear algebra:

The ket $|a\rangle$ is a column vector.

The bra $\langle a|$ is a row vector.

The bra-ket $\langle a| b \rangle$ is a comparison.

The ket-bra $| a \rangle\langle b|$ is a transformation.

Fundamentally, the brackets are nothing more than a reminder for "that's a row vector" vs "that's a column vector". If the angle bracket is pointing left, like $\langle a|$, then it's a bra; a row vector. If the angle bracket is pointing right, like $| a \rangle$, then it's a ket; a column vector. You can also think of the brackets as a mnemonic tool for tracking if you're working with a vector or its conjugate transpose, since $| a \rangle = \langle a |^\dagger$.

But this mere mnemonic is more useful than it seems. In particular, by creating a clear visual difference between inner and outer products, it adds surprising clarity when combining vectors.

When you multiply a bra $\langle a |$ by a ket $|b\rangle$, with the bra on the left as in $\langle a | b \rangle$, you're computing an inner product. You're asking for a single number that describes how much $a$ and $b$ align with each other. If $a$ is perpendicular to $b$, then $\langle a | b \rangle$ is zero. If $a$ is parallel to $b$, and both are unit vectors, then $\langle a | b \rangle$'s magnitude is one. For the in-between cases, you get something in-between.

When you flip the order and multiply a ket $| a \rangle$ by a bra $\langle b |$, with the ket on the left as in $| a \rangle\langle b |$, you're computing an outer product. $|a\rangle\langle b|$ isn't a single number, it's a whole matrix! A matrix that converts between $a$ and $b$, to be specific. If you left-multiply $|a\rangle\langle b|$ by $\langle a |$, you end up with $\langle b |$. If you right-multiply $|a\rangle\langle b|$ by $|b\rangle$, you end up with $|a\rangle$. Why? Because of associativity: $|a\rangle\langle b| \cdot |b \rangle = |a\rangle \cdot \langle b|b \rangle = |a\rangle \cdot 1 = |a\rangle$. (Note: assuming $a$ and $b$ are unit vectors.)

You can think of a single ket-bra like $| a \rangle \langle b|$ as a matrix building block. To make a big complicated matrix, you just add together a bunch of blocks. You want a matrix $M$ that turns $a$ into $b$ and turns $c$ into $d$? Easy! Just add them together! As long as $a$ is perpendicular to $c$, then $M = |a\rangle \langle b| + |c\rangle \langle d|$ will do exactly what you want. (If $a$ isn't perpendicular to $c$, you need to add a corrective term... depending on exactly what you want to happen. Keep in mind that vectors with components parallel to $a$ are partially transformed by $|a\rangle \langle b|$ due to linearity.)

This means that, instead of writing a matrix as a big block of numbers:

$$A = \begin{bmatrix} A_{0,0} & A_{0,1} & A_{0,2} & A_{0,3} \\ A_{1,0} & A_{1,1} & A_{1,2} & A_{1,3} \\ A_{2,0} & A_{2,1} & A_{2,2} & A_{2,3} \\ A_{3,0} & A_{3,1} & A_{3,2} & A_{3,3} \end{bmatrix}$$

We can write the matrix as a sum over two indices, by defining "$|k\rangle$" to be the vector with zeroes everywhere except for a one in the $k$'th entry:

$$A = \sum_{i} \sum_{j} A_{i,j} |i\rangle\langle j|$$

This summation form is naturally more amenable to algebraic manipulation.

Automatic Matrix Multiplication

I've always had trouble multiplying matrices. I can do it, it's just... I really easily make tranposition mistakes. I'll zip the columns of the left matrix against the rows of the right matrix instead of vice versa, or I'll second guess zipping the rows against the columns, or I'll forget if I decided that the first index should be the row or the column, or... Suffice it to say it's always been a frustrating mess.

... Until I learned bra-ket notation.

Recall that we can break a matrix into parts like so:

$$A = \sum_{i} \sum_{j} A_{i,j} |i\rangle\langle j|$$

$$B = \sum_{i} \sum_{j} B_{i,j} |i\rangle\langle j|$$

So if we're faced with a matrix multiplication:

$$P = A \cdot B$$

We can just... do a normal multiplication with standard series manipulations. Really.

Start by expanding the definitions of the matrices:

$$P = \left( \sum_{i} \sum_{j} A_{i,j} |i\rangle\langle j| \right) \cdot \left( \sum_{k} \sum_{l} B_{k,l} |k\rangle\langle l| \right) $$

Suddenly there's all this structure to work with. For example, because multiplication distributes over addition, we can move the summations around. Let's move them all to the left:

$$ P = \sum_{i} \sum_{j} \sum_{k} \sum_{l} A_{i,j} |i\rangle\langle j| B_{k,l} |k\rangle\langle l| $$

Matrix multiplication isn't commutative, but $A_{i, j}$ and $B_{k, l}$ are scalar factors. We can at least move those around safely. Let's get them out of the way, by pushing them to the right:

$$ P = \sum_{i} \sum_{j} \sum_{k} \sum_{l} |i\rangle\langle j| |k\rangle\langle l| A_{i,j} B_{k,l} $$

Notice that the comparison $\langle j|k\rangle$ just appeared in the middle of the summand. The result of a comparison is a scalar, and scalars can be moved around freely, so let's put the comparison with the other scalars on the right:

$$ P = \sum_{i} \sum_{j} \sum_{k} \sum_{l} |i\rangle\langle l| \cdot \langle j|k\rangle A_{i,j} B_{k,l} $$

Now it's clear that the sums over $i$ and $l$ are the ones building up the overall structure of the matrix, while the $j$ and $k$ sums work on the individual entries. Let's re-order the sums to match that structure and pull $|i\rangle\langle l|$, the outer product term, uh, outward:

$$ P = \sum_{i} \sum_{l} |i\rangle\langle l| \sum_{j} \sum_{k} \langle j|k\rangle A_{i,j} B_{k,l} $$

There's one last important thing to notice: the comparison $\langle j | k \rangle$ is almost always zero. Anytime $j$ differs from $k$, $\langle j | k \rangle$ is comparing totally orthogonal basis vectors. That means that, in the sum over $k$, the only summand that matters is the one where $j=k$. We don't need to sum over $k$, we can just re-use $j$!

$$ P = \sum_{i} \sum_{l} |i\rangle\langle l| \sum_{j} \langle j|j\rangle A_{i,j} B_{j,l} $$

$\langle j | j \rangle$ is 1, because $|j\rangle$ is a unit vector, so we simply drop the $\langle j | j \rangle$ term. That leaves:

$$ P = \sum_{i} \sum_{l} |i\rangle\langle l| \sum_{j} A_{i,j} B_{j,l} $$

Or, written another way:

$$(A \cdot B)_{i, l} = \sum_{j} A_{i,j} B_{j,l}$$

Which is the definition of matrix multiplication that I was taught in school.

I really want to emphasize how different this approach to matrix multiplication feels, to me. There was no worrying about rows-vs-columns, or about the order of indices. I just plugged in the sums, turned the crank, and out popped the first matrix multiplication I ever did without second-guessing every step.

Other Niceties

Thinking with bras and kets makes many trivial problems actually trivial (at least for me). For example, I always had a hard time remembering if $X \cdot Z$ would negate the Off or On state of an input. With bra-kets I just think "Okay $X$ is $|0\rangle\langle 1| + |1\rangle\langle 0|$ and $Z$ is $|0\rangle \langle 0| - |1\rangle \langle 1|$, so $X \cdot Z$ is..., right, duh, it negates $\langle 0 |$s coming from the left and $| 1 \rangle$s coming from the right.".

Another thing I find useful, when working with kets and bras, is that you don't need to think about the size of a matrix. $|0\rangle \langle 1|$ acts the same regardless of whether you logically group it with other transformations into a 2x2 matrix, a 3x3 matrix, or a 100x2 matrix. All notions of multiplications having "matching sizes" are made irrelevant by unmatched inputs or outputs automatically being zero'd away.

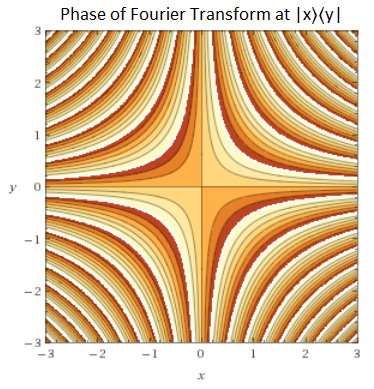

Bra-ket notation is also flexible enough to describe linear transformations on infinite spaces, including continuous spaces. The continuous Fourier transform? That's just the 'matrix' $F = \int \int |x\rangle \langle y | \cdot e^{x y \tau i} \,dx \,dy$:

We're not done yet! Ever wonder why eigendecomposing a matrix is so useful? So did I, until I saw how easy it is to manipulate terms like $\sum_k \lambda_k |\lambda_k\rangle \langle \lambda_k|$. Especially if the $|\lambda_k\rangle$'s are orthogonal.

Finally, bra-ket notation enables other useful shorthands. For example, $\langle A \rangle$ is short for "the expected value of the observable $A$" (literally $\langle v | A | v\rangle$ for some implied $v$). This makes defining the standard deviation trivial, for example: $\text{stddev}(X) = \sqrt{\langle X^2 \rangle - \langle X \rangle^2}$. I also find myself creating constructs like $\sum_k \ket{n \atop k} \bra{n \atop k}$, which succinctly defines the projector for the symmetric subspace of $n$ qubits without straying too far into new notation.

So the benefits go beyond simple matrix multiplication.

Summary

Bra-ket notation lets you split matrices into sums of useful building blocks. Turns out this is a pretty good idea. Good enough that I think it should be taught to everyone, not just physicists, as part of the standard linear algebra curriculum.