The Elitzur-Vaidman bomb tester is one of the funnest quantum devices to teach people about. It uses the quantum Zeno effect to safely separate dud bombs from live bombs, even when the only way to "test" a bomb is by triggering it! The main caveat is that the dud bombs have to broken in a specific way: instead of being triggered by a single passing photon, they must fail to interact with the photon at all.

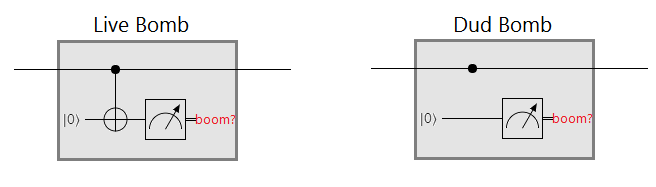

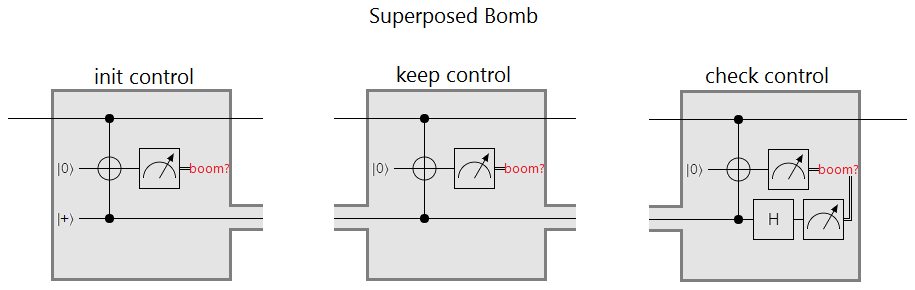

For clarity, let's translate the bombs into quantum circuits. The circuit element corresponding to a live bomb is a CNOT gate onto a fresh ancilla, followed by a measurement to check if the bomb should explode. The dud bomb's circuit element is the same as the live bomb's, but with the NOT gate removed:

The goal of the Elitzur-Vaidmain bomb tester is to distinguish between the above two circuits. Without causing a kaboom. You can run as many qubits as you want through the bomb-or-dud black box, but if the internal wire ever goes high then the bomb explodes and you lose. You win if there's no explosion and your circuit outputs an OFF qubit for live bombs and an ON qubit for dud bombs.

If you've never seen this problem before, I recommend stopping here and trying to solve it for yourself because I'm about to spoil it.

...

...

...

...

You're sure?

...

...

...

...

Alright, here comes the spoilers.

The Bomb Tester

The trick to telling if a bomb is live or a dud, without setting the bomb off, is to run a single qubit through the bomb again and again while very slowly rotating the qubit from OFF to ON.

If the bomb is a dud, the rotations add together until the qubit has rotated all the way to ON. We stop after the appropriate number of passes, measure the qubit, get an ON result, and see that yes indeed this is a dud bomb.

If the bomb is live, then after each rotation there's a chance the bomb will explode. If we're rotating by $\theta$ radians, that chance equals $\cos^2 \theta$. But the bomb exploding or not is a measurement of the qubit. When the bomb doesn't explode we've collapsed the qubit back into the OFF state. This means the rotations don't add up like they do in the dud case. As long as the bomb doesn't explode, we keep ending up back in the OFF state. So we'll get an OFF result when measuring the qubit at the end of the circuit, and conclude the bomb is live... if we survived.

How likely is it that we survive all of the passes when dealing with a live bomb? Assuming we do $n$ passes, having to rotate by the correct amount in the dud case forces a per-pass rotation of $\theta = \pi/(2n)$. Given $n$ and the corresponding $\theta$ we can compute the overall chance of surviving every pass. It's $p_n = (\cos \frac{\pi}{2n})^{2 n}$. Note that $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} p_n = 0$. That's the Zeno effect in action: constant measurements overpower sufficiently tiny rotations. By increasing $n$, we can, with probability arbitrarily close to 1, keep the state OFF without exploding any bombs.

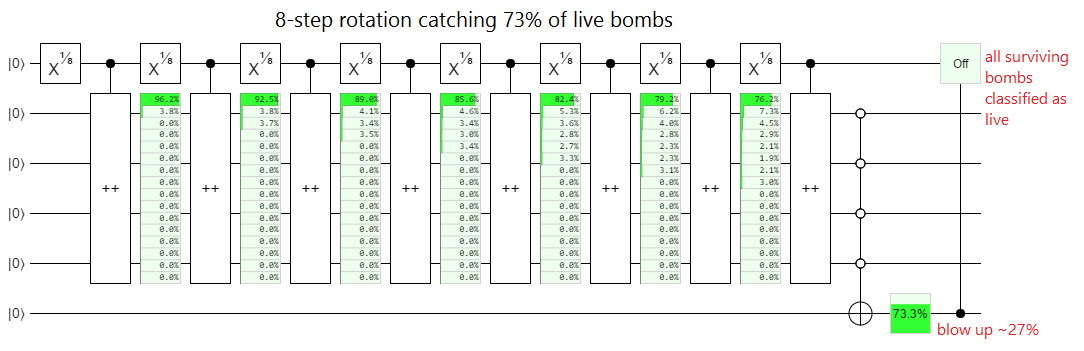

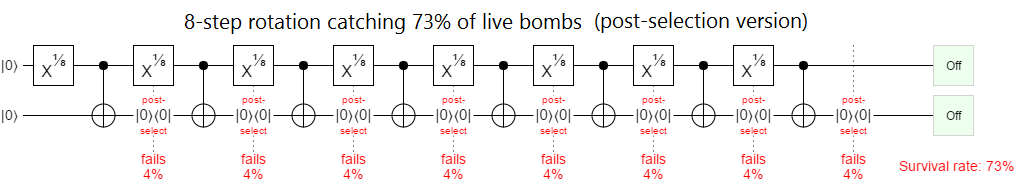

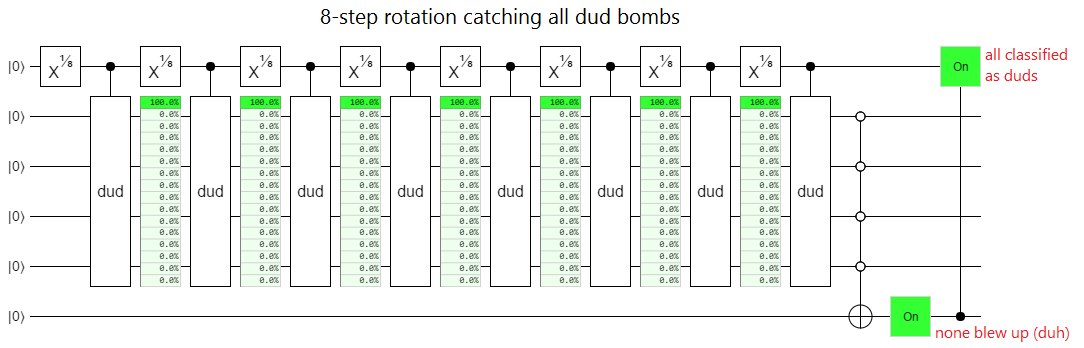

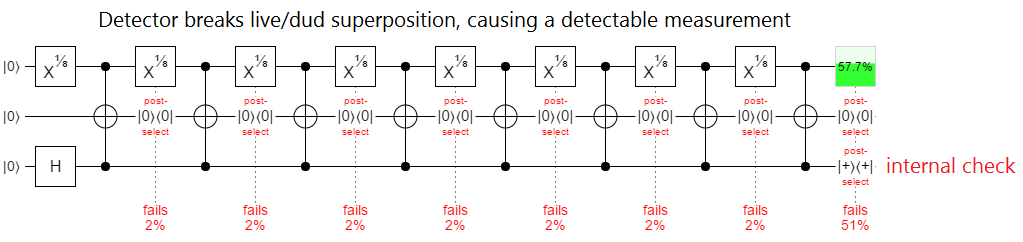

This is all somewhat counter-intuitive, so let's go over the numbers with $n=8$. Given a live bomb, there's a $p_8 = (\cos \frac{\pi}{16})^{16} \approx 73.3\%$ chance it will survive. If it survives, there's a 100% chance we measure OFF and conclude it's live. Given a dud bomb, there's a 100% chance we measure ON and conclude it's a dud. We can confirm these numbers by simulating the bomb circuits in Quirk.

About a quarter of the live bombs explode, but the rest output OFF:

Note that, because Quirk doesn't let you recohere qubits, I represented the live bombs with increment gates instead of CNOTs to save space. Otherwise I would have had to use a new qubit for each CNOT. An even more compact alternative, which I'll be using elsewhere in this post, is post-selection gates:

Dud bombs, which do nothing, output ON and don't explode:

If we increase from $n=8$ to $n=100$, the live bomb losses decrease from $26.7 \%$ to $2.4 \%$. And at $n=1000$ the losses are a mere $0.5 \%$, with the trend continuing downwards towards 0 hyperbolically as $n$ increases (i.e. $p_n$ is asymptotically equal to $1/n$).

Now that you understand the bomb tester, let's consider a hypothetical practical application.

Hidden Beam Alarms

In heist movies, a common trope is the 'laser hallway':

There, at the far end of the room, sitting on a pedestal, is the target: the famous Maltese MacGuffin. But there's one little problem. Between here and there is an array of highly visible laser beams, and crossing one will set off the alarm system. Time for a highly improbable series of backflips, cartwheels, and similar moves.

Of course, in real life, beam alarms aren't as flashy as they are in the movies. For starters, they use infrared light so you can't see the beams. Even if the air is foggy or dusty.

That being said, infrared beams are still detectable with the right equipment. The ideal beam detector would be truly undetectable. That's where the Elitzur-Vaidman bomb tester and the Zeno effect suggest interesting possibilities.

Consider: what if we made a beam alarm that worked like the bomb tester? Instead of just sending a photon across a hallway, we put its path into a superposition of travelling across the hallway and through a fiber optic line below the hallway. Initially the photon is only travelling along the line below the hallway, but as we bounce the photon back and forth we use beam splitters to apply small rotations to the path superposition.

If there's nothing in the hallway beam path then these rotations will add up and the photon will gradually transition to being entirely on the hallway path. But if there is something in the hallway, then the Zeno effect will pin the photon to the fiber optic path. Because the Zeno effect is keeping the photon from taking the hallway path, no photon-detector in the hallway beam path will be set off. After $n$ bounces we can measure which path the photon is on and VOILA!, we've checked if something is in the hallway in an apparently undetectable way.

(Side note. I should mention that, in practice, there would be complications. For example, air could scatter the photons. Or someone could step into the beam only at the end of the path-rotating process. But, putting those and other caveats aside, this does appear at first glance to be an undetectable way to check if someone is standing in the hallway.)

In fact, if we limit the hallway denizens to classical detectors, then this Zeno-effect beam alarm really is undetectable in the limit. Modulo practical issues. But consider: the alarm is telling us information about what's in the hall. It must be doing some kind of measurement to do that. And quantum systems are perturbed by measurements...

Zeno Detector Detectors

So far I've mentioned two types of bombs. Dud bombs, which do nothing, and live bombs, which do a controlled operation. To detect the quantum bomb tester we need a third type of bomb: the superposed bomb.

Superposed bombs have an internal qubit that determines whether the bomb acts like a dud bomb or like a live bomb. But the internal qubit isn't kept ON or kept OFF, it's kept in superposition. It's initialized to the state $|+\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt 2}|0\rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt 2}|1\rangle$. The bomb then periodically checks whether the control qubit is still in the state $|+\rangle$ by doing an $X$-axis measurement (i.e. a $|+\rangle$ vs $|-\rangle$ measurement). If the internal qubit is in the wrong state... KABOOM!

The trick here is that, since the internal qubit determines whether this bomb acts like a dud bomb or like a live bomb, any detector that distinguishes between the two must have measured whether the internal qubit is ON or OFF. But if the internal qubit was measured then it has ended up OFF, or ON, and in either case an $X$-axis measurement will have a random result. Basically, if you run this thing through an Elitzur-Vaidman bomb tester instead of leaving it alone, there's at least a 50% chance it'll blow up in your face:

Note that the superposed bomb is still technically vulnerable to the Zeno effect, but the detector isn't in control of how often the state is measured anymore. The bomb decides how often to check, and the period could be set appropriately based on the situation.

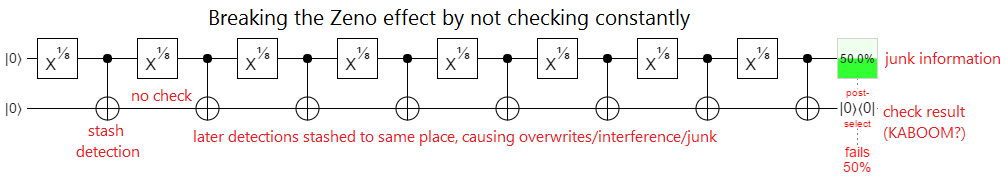

Further note that similar detector detection effects can be achieved even without the internal control. Almost any mechanism that breaks the Zeno effect will do. For example, instead of checking the "bomb triggered" information constantly, just keep it coherent for awhile:

What this all means is that our hypothetical zeno-effect beam alarm works on some hallway obstacles, but not all obstacles. Obstacles capable of doing quantum computation on the beam photons have a chance of detecting the beam, decreasing the chance of being detected, and even slipping by undetected.

At this point it should be clear that this whole business of detector detection is more complicated than it seems. We're trying to do process tomography on systems with internal states that are out of our control, without affecting those internal states. The fact that we can tell live bombs from dud bombs under these constraints is fascinating, but this is a power with limits. There are some systems that a given detector just won't be able to reliably tell apart without causing side effects.

Instead of ending the arms race between detectors and detector-detectors, quantum computation just complicates the problem even more.