I've been thinking about circuit constructions lately, and the question occurred to me: if circuit $A$ uses $O(N)$ gates and circuit $B$ uses $O(N^2)$ gates, but in parallel and with a better constant factor so that $B$'s depth is a bit better than $A$'s, would you ever use $A$ instead of $B$? Can lowering the width (i.e. number of operations being applied in parallel on average) of a circuit ever justify increasing the depth?

Early quantum computers aren't going to be applying circuit operations on separate qubits one after another after another, they're going to be applying operations in parallel. The ultimate determiner of execution time is going to be depth, so why should I give any thought to width?

After thinking about it for a bit, I came up with three possible reasons to care about circuit width. They are: borrowability, locality, and simulability.

Borrowability

Many quantum circuits can be made more efficient if they have access to ancilla bits. Ancilla bits aren't used for input or output; they're just extra workspace you can use temporarily. Even ancilla that aren't in a known state ("dirty bits") are useful. For example, a single ancilla in an unknown state can cut the cost of incrementing a register in half.

Because ancilla can be so useful, it pays to have lots of them available. And since any qubit that isn't being used right now can be temporarily borrowed as a dirty ancilla, one way to have lots of ancilla available is to not be touching qubits all the time. Circuit constructions with a high width are using a larger fraction of qubits at any given time, and so provide fewer opportunities for borrowing to other parts of the circuit.

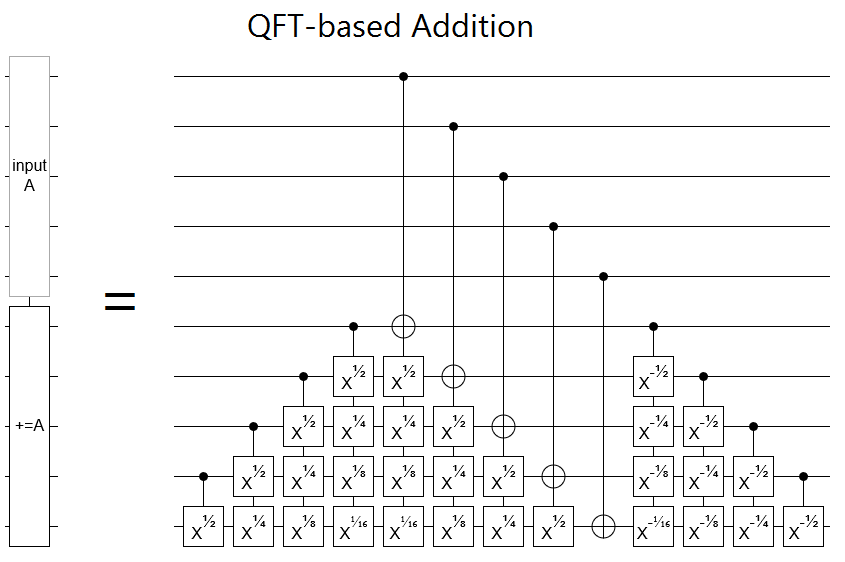

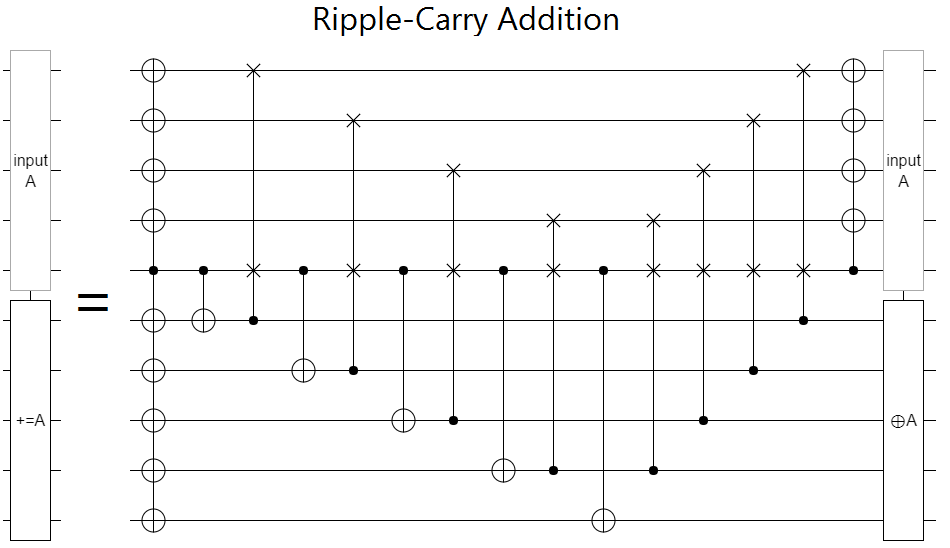

For example, consider the follow two addition circuits, one based on the Fourier transform and the other based on ripple-carries:

These naive constructions have the same asymptotic depth, but the qft addition is much wider. (Actually, it's even wider than it looks because on an actual quantum computer a qubit can probably only control one thing at a time. Also, it's a bit misleading to look at a 5-bit adder since the quadratic costs haven't really kicked in at such a small size.)

Now suppose that these adders were a small part of a larger computation, and elsewhere in the global circuit there were a lot of other operations that would benefit from borrowing dirty ancilla. The ripple-carry adder has a lot more space where qubits aren't touched for a proportionally long time. And, if the processes borrowing the ancilla also have a sweeping-up-and-down kind of shape so the ancilla they borrow can be subleased to yet more circuits then things fit together particularly nicely.

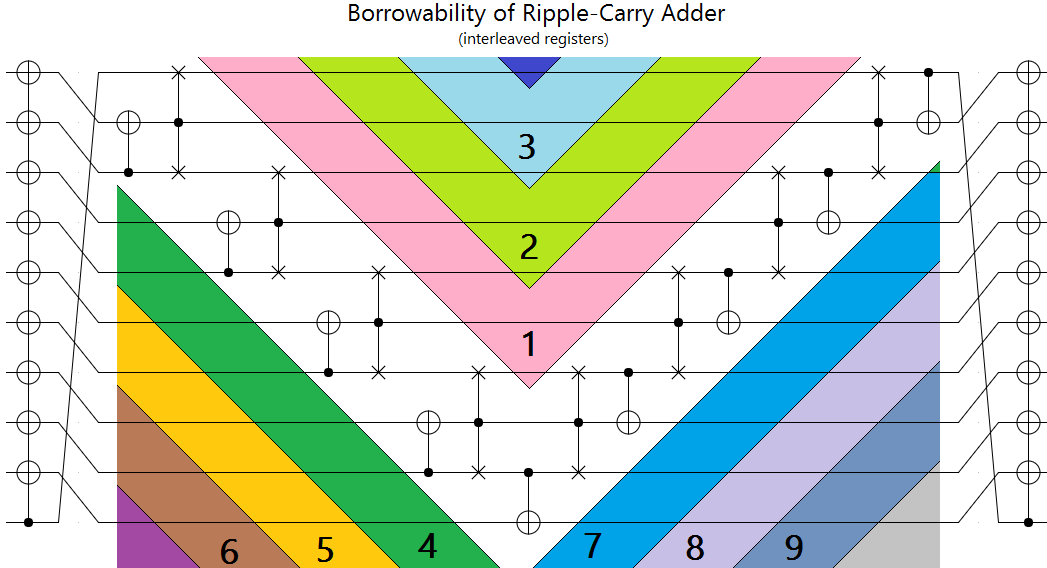

This is a lot clearer if you re-arrange the ripple-carry circuit so that the input and output bits are interleaved instead of grouped:

The above diagram shows the large number of "sweep tracks" available when using the ripple-carry adder.

Now, to be fair, I don't know whether "borrowability" optimizations will end up mattering. And the QFT-adder isn't a particulary great example, since it does have space available for borrowing. Clearly the benefits are going to vary from case to case. Still, if we're in a situation where ancilla are in high demand and our part of the circuit isn't the "long poll", then using low-width constructions might be a big win.

Locality

Notice that the low-width circuit from the previous section was very "sweepy". The operation travelled across the qubits applying local gates, turned around, travelled back, and finished. "Sweepyness" is typical of low-width circuits, because if an operation doesn't depend on a qubit touched by the previous operation then you would have run that operation earlier and saved on depth. A minimal-width construction has to be a narrow chain of operations bouncing around the circuit. By contrast, low-depth high-width constructions are more "mixy". They tend to chaotically interact everything with everything else.

Now suppose you have a quantum computer with a very restrictive topology, like a surface code chip, where only neighbors can talk. If two qubits need to interact, it could take a lot of work to move them to adjacent positions! For "sweepy" interactions this isn't a big deal, because you have fewer constraints on where things have to be and each thing has more dead time that can be repurposed into movement time. But if you have lots of overlapping chaotic interactions, you won't be able to keep up and will pay huge time penalties just swapping things into position.

For example, the ripple-carry adder only has to move a single signal (the carry) across the registers. Put the two registers on adjacent rows, and you're essentially done. There is a similar optimization for the QFT adder, but you need to borrow a third adjacent register to make it work.

Locality is probably going to be a very important consideration when designing quantum circuits. Even with tricks like streaming entanglement across the chip to feed quantum teleportation so that some qubits are effectively closer together. Circuit constructions that are more amenable to localization will have a huge advantage over other circuits.

Simulability

Quantum circuit simulators tend not to run operations on separate qubits in parallel. They do one operation after another. That's because, from the perspective of the amplitude vector, an individual operation is already an embarrassingly parallel task that can keep all your CPUs and GPUs busy. There's nothing left over for doing inter-operation parallelization.

So, from the perspective of classical simulation, size matters far more than depth. That being said, this is a pretty weak reason. As soon as we have decent-sized quantum chips, classical simulation starts being intractable anyways.

Closing Remarks

At this early time, it's hard to say exactly what kinds of quantum circuits will be best or even what metrics will end up mattering. But I do think one thing is clear: we're sure going to find out. The pressure to optimize circuits designed to run on early quantum computers is going to be insane.

Ever hear stories about people scrounging for every. single. bit. to make something work in the 1980s? Early quantum computers are going to have literally tens of thousand of times less space than those machines. We're going to have less space than the frickin ENIAC! And, on top of those insane space constraints, non-error-corrected qubits don't stay coherent very long. So early quantum circuits will also be heavily time limited. Cutting the cost of a quantum circuit by 20% could literally mean you get to run it a whole year earlier.

So why care about circuit width? Because we're gonna be under such heavy constraints that we have to care about everything.