Historically speaking, I think it's fair to say that quantum computing papers have often assumed that, when it comes to conditionally applying an operation, it's better for the conditionion to be classical. It makes intuitive sense, after all. Instead of having to do some complicated multi-qubit interaction, you just either do or don't do the operation.

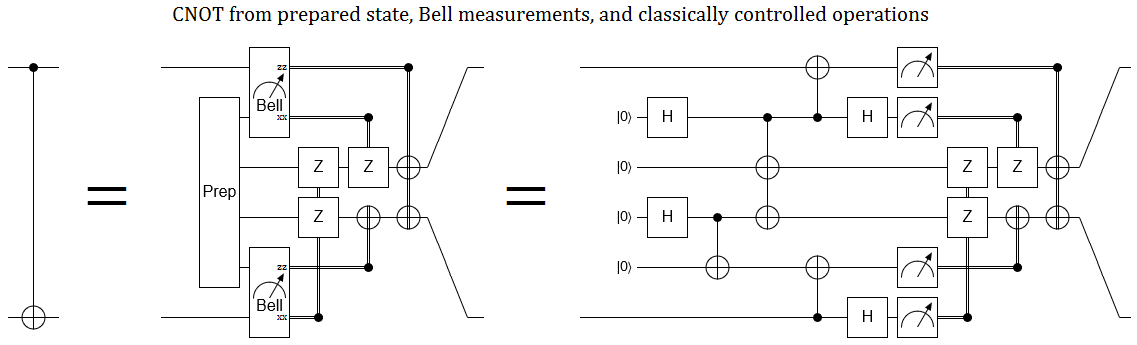

For example, the paper "Quantum Teleportation is a Universal Computational Primitive", by Gottesman and Chuang, suggests replacing CNOT gates with this construction:

Although the above construction appears to use many quantum CNOTs to perform a single CNOT, the CNOTs used by the circuit are "okay" because they are either a) part of a preparation phase that can be repeated until you get it right or b) part of a Bell basis measurement (which happens to be easy to do, at least with photons). The rest of the operations are all single-qubit operations that either happen or don't happen depending on the outcomes of some measurements. The idea is that this is easier to do than the original quantumly-controlled NOT.

From the perspective of computing with photons, Gottesman and Chuang's construction makes some amount of sense. But, from the perspective of other kinds of quantum computers, replacing a CNOT with a series of measurements and corrective operations looks a bit... insane? Especially early on in the history of quantum computing, when qubits are likely to have short lifetimes. I think the salient problems of that era, our era, are almost exactly opposite to the intentions of the above construction.

For example, suppose you have a qubit with a short lifetime. One millisecond, for argument's sake. During that millisecond you can apply a few thousand operations. In order to classically control one of those operation, you need to:

- Perform a measurement.

- Get the measurement out of the quantum hardware and into a classical computer.

- Classically compute what to do.

- Get the resulting decision back into the quantum hardware.

- Apply the operation (or not).

The problem with all this is that, while the result-to-operation process is happening, the qubits are just... waiting. Decohering. Fast. Delays are very, very bad when your qubits die in the blink of an eye (actually, in this example, it's more like a hundredth of a blink).

For reference, a "good ping" when playing a multiplayer action game is ~30 milliseconds. And, according to "Latency Numbers Every Programmer Should Know", a round trip within a data center is half a millisecond. Given our hypothetical qubit lifetime of 1ms, the "good ping" is hilariously slow. Even the datacenter round trip is way too high. With those kinds of latencies, we might get in two whole operations before the qubits die!

Clearly any setup where the controlling computer isn't directly hooked up to the quantum computer is just not going to work. The other steps in the classical control process also use up precious time. Measurement takes time. Deciding what to do takes time. Getting operations ready to apply takes time. If any of those steps are slow, that's game over; you computed noise. So you probably don't just need nearby hardware: you need specialized nearby hardware.

Given the extreme time constraints on early classical control, I feel a kind of culture shock when reading papers that just assume classical control is easy. No doubt clasical control will be easy eventually, when we have qubits whose lifetimes are measured in days instead of milliseconds, but early on I think it will be quite difficult. Something to think about.