Lately, as part of writing a paper, I've been thinking about quantum circuits for doing multiplication while using very little workspace. Surprisingly, this stumbled me into a nice way to compute multiplicative-inverses.

Consider that multiplying by 3 is equivalent to adding a register into itself, left-shifted:

def times_3(value):

value += value << 1

return value

The above code is simple, and looks like it's being computed inline, but doesn't translate directly into a no-workspace quantum circuit. The problem is that the same bits would need to act as both inputs and outputs. Fixing this requires splitting the addition into parts where the bits being added-from are distinct from the bits being added-into.

The fix isn't too hard. Incrementing a low bit of a register can carry into the high bits, but incrementing high bits never causes carries into low bits (when working modulo a power of 2). So, as long as we work from high to low, we can do the shifted addition bit by bit:

def times_3(value, register_size):

register_mask = ~(~0 << register_size)

for i in reversed(range(register_size)):

if value & (1 << i):

value += 2 << i # only affects bits above i

value &= register_mask

return value

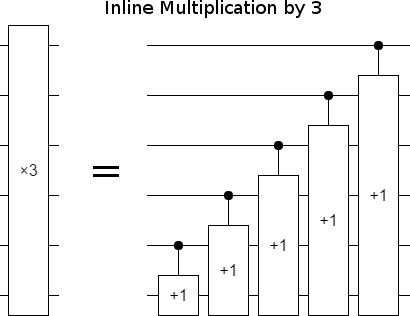

The above algorithm looks even simpler in the form of a circuit diagram:

As soon as I saw the above circuit, I realized that this shifted-addition approach generalizes to any odd scaling factor $K$.

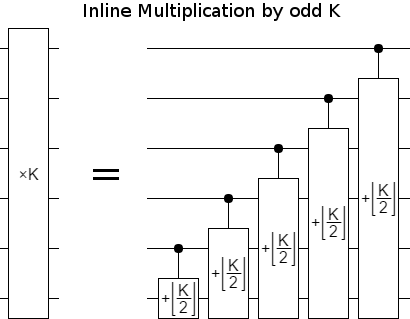

Just change the amount being added from $1$ to K >> 1, or equivalently $\lfloor K/2 \rfloor$:

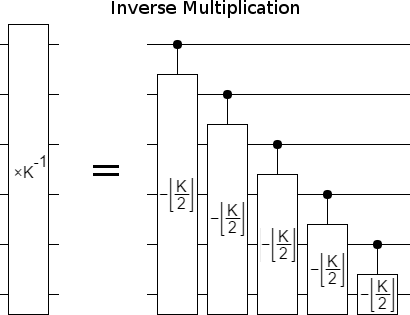

Continuing the train of thought, as soon as I saw that circuit I realized that running it backwards must multiply by $K^{-1} \pmod{2^n}$. After all, every quantum circuit is reversible and the reverse of multiplying by $K$ is multiplying by $K^{-1}$.

To create a $\times K^{-1}$ circuit, all we have to do is take the $\times K$ circuit, invert the additions into subtractions, and reverse the order of operations:

This is kind of neat, because the construction only uses $K$ but the effect is in terms of $K^{-1}$. In fact, we can use this to compute $K^{-1}$. Just consider what must happen when the inverse-multiplication circuit is applied to a register storing $|1\rangle$. The output would be the multiplicative inverse, because $|1 \cdot K^{-1}\rangle = |K^{-1}\rangle$.

Keep in mind that, although I've been talking in terms of "quantum" circuits, all the operations in the discussed circuits have been classical. We're still in the regime of classical computing. We can translate the diagram back into python code.

The result is a nice and simple multiplicative inverse method. It only works for powers of 2, but it's much easier to remember than the usual extended-gcd algorithm. Here's the code:

def multiplicative_inverse_mod_power_of_2(factor, bit_count):

rest = factor & ~1

acc = 1

for i in range(bit_count):

if acc & (1 << i):

acc -= rest << i

mask = ~(~0 << bit_count)

return acc & mask

Not bad!

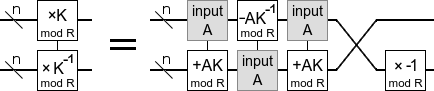

I tried to extend this idea to computing multiplicative inverses when the modulus isn't a power of 2. Unfortunately, all the modular multiplication circuits that I know need the multiplicative inverse as part of constructing the circuit. Also, because modular arithmetic breaks the "high bits don't carry into low bits" property, the circuits aren't inline. For example, here's a modular multiplication circuit from the paper:

Notice that one of the operations is subtracting the bottom register times $K^{-1}$ out of the top register. Constructing this operation requires knowing $K^{-1}$, so it would be paradoxical to use the operation to find $K^{-1}$. (You might think that reversing the $+AK$ circuits would create $-AK^{-1}$, but actually it creates $-AK$.) Maybe this is a hint that, in order to find an efficient inline modular multiplication circuit, we need to fix the fact that the current ones don't look at all like the computation of a multiplicative inverse.

(Bonus: While playing around with this problem, I tried framing a multiplication gate with a quantum fourier transform. Turns out this inverts the multiplication! Formally: $QFT \circ (\times K) \circ QFT^\dagger = \times K^{-1}$. Of course it's much more efficient to just reverse the $\times K$ circuit. But, as I mentioned last post, knowing a framing operation that inverts effects makes for cheap controls.)