Suppose you have two qubits. For evocative purposes, suppose you're literally holding them as balls in your hands: one in the left hand, and one in the right hand. Your goal is to swap the qubits, so that your right hand ends up holding a qubit storing the state of the qubit currently in your left hand (and vice versa). How do you do it?

Okay okay, that's not very hard. Obviously you can just physically move the qubits between your hands. Put one qubit down, pass the other qubit to the opposite hand, then pick up the qubit you put down.

But what if they were glued to your hands?

That sounds funny, but it's not intended as a joke. In practice, it's not always possible to physically move qubits. For example, your qubits might be etched onto a circuit board hidden away inside a dilution refrigerator. You're going to have a bit of trouble moving those around.

Even if you can't literally physically swap the two qubits, it's still possible to swap their states. As long as you have the right operations available. For example, if I allow you to apply Hadamard gates (a single-qubit operation that rotates 180 degrees around the diagonal X+Z axis, transitioning the $|0\rangle$ state to the state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|0\rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|1\rangle$ and the $|1\rangle$ state to the state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|0\rangle - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|1\rangle$) and Controlled-Z gates (a two-qubit interaction that negates the amplitude of the $|11\rangle$ state), then there is a series of operations you can do to swap the states of the qubits.

We'll get to that specific case in a bit. The point is that, in this post, we're talking about swaps. We'll cover a few ways to do swaps, how to generalize swaps, and how to specialize swaps.

Bit Twiddling and Xor-Swapping

One of my favorite websites is Bit Twiddling Hacks. It's a bunch of low-level programming tricks for computing simple functions in few operations, and it's fantastic. For example, do you need to count the number of one-bits in a 32 bit register? It's possible to do so in 12 ops, and that site will show you how.

One of the bit twiddling tasks on the site is "swap two variables without using any extra space for a temporary variable".

That is to say, rewrite the following code so that it operates only on a and b without using a temporary t:

# swap a, b using temporary t

int t = a;

a = b;

b = t;

(No, using a language that lets you write a, b = b, a doesn't count as a solution.)

One solution to this problem, covered by the Bit Twiddling Hacks site, is called "xor-swapping". You just xor-assign the two variables back and forth and back, and they end up swapped:

# swap a, b

a ^= b

b ^= a

a ^= b

To really see why this works, I recommend doing a few examples by hand. For our purposes here in this post, the interesting thing about xor-swapping is that it only uses reversible operations. Which means it will work on qubits.

The statement a ^= b means "for each bit position, if the bit at that position in b is on then toggle that bit in a".

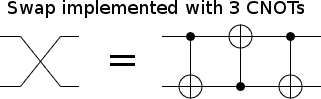

There is a quantum equivalent of this "if b then toggle a" operation: the Controlled-Not ("CNOT") gate.

Thanks to the CNOT, we can implement a xor-swap on a quantum computer.

All we need to do is chain three CNOTs back and forth:

Let's go through the four basis cases to see why this works:

- $|00\rangle$: Desired output is $|00\rangle$.

- The first CNOT's control is not satisfied. We stay in the state $|00\rangle$.

- The middle CNOT's control is not satisfied. We stay in the state $|00\rangle$.

- The final CNOT's control is not satisfied. We stay in the state $|00\rangle$. Correct.

- $|01\rangle$: Desired output is $|10\rangle$.

- The first CNOT's control is not satisfied. We stay in the state $|10\rangle$.

- The middle CNOT's control is satisfied. The bottom qubit gets toggled. We transition to the state $|11\rangle$.

- The final CNOT's control is satisfied. The top qubit gets toggled. We transition to the state $|10\rangle$. Correct.

- $|10\rangle$: Desired output is $|01\rangle$.

- The first CNOT's control is satisfied. The top qubit gets toggled. We transition to the state $|11\rangle$.

- The middle CNOT's control is satisfied. The bottom qubit gets toggled. We transition to the state $|01\rangle$.

- The final CNOT's control is not satisfied. We stay in the state $|01\rangle$. Correct.

- $|11\rangle$: Desired output is $|11\rangle$.

- The first CNOT's control is satisfied. The top qubit gets toggled. We transition to the state $|10\rangle$.

- The middle CNOT's control is not satisfied. We stay in the state $|10\rangle$.

- The final CNOT's control is satisfied. The first qubit gets toggled. We return to the state $|11\rangle$. Correct.

So all four classical cases work. But what about the quantum cases? The qubits could be in superposition, entangled with other qubits, entangled with each other, etc. For example, the state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|0\rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|1\rangle$ is unaffected by NOT gates. Couldn't initializing the bottom qubit to that state prevent the first CNOT from achieving its purpose, thereby ruining the swap?

The short answer to this worry is a rule of thumb: quantum mechanics is linear, so if it works for the basis states then it works for every state. There are exceptions to this rule, but only for circuits involving extra work qubits (e.g. the phase kickback used in Shor's algorithm). Our circuit has no extra qubits, so we're fine.

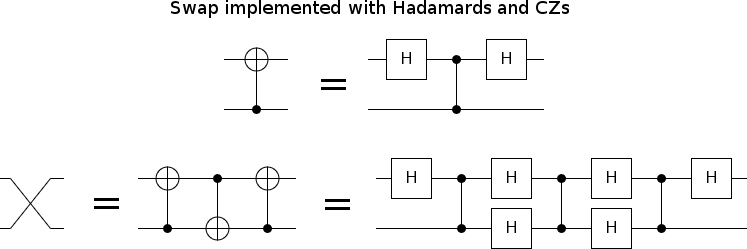

Xor-Swapping with Hadamards and CZs

We now know how to swap two qubits by applying CNOT gates to them. If we don't have CNOTs available as a basic gate, we can still use this strategy. We just need to build the CNOTs out of our available gates. For example, the gate set I mentioned at the start of this post (CZ+H) doesn't include a CNOT, but it's still possible to build a circuit equivalent to a CNOT.

Take a CZ gate, and apply a Hadamard before/after the gate on one of the qubits. The net effect is a CNOT, with the Hadamard-framed qubit as the target:

Why does this work? It has to do with the reason that, in quantum computing, we call the NOT gate "X" and the phase-flip gate "Z".

The Hadamard operation is a 180 degree rotation around the X+Z axis of the Bloch sphere. If you have a state along the X-axis of the Bloch sphere (e.g. $|X^{\text{on}}\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|0\rangle - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|1\rangle$), the Hadamard operation will rotate that state to a state along the Z axis (i.e. $|Z^{\text{on}}\rangle = |1\rangle$). Analogously, the Hadamard will rotate Z-axis states onto the X-axis. For this reason, framing an operation with Hadamards converts any interactions along the Z-axis into interactions along the X-axis, and vice versa. The NOT gate is an X-axis interaction, the phase-flip gate is a Z-axis interaction, and so Hadamard operations turn one into the other.

For more discussion of this "NOT as X-interaction" stuff see the post "Thinking of Operations as Controls", but I'll cover a bit here. Basically, a CZ gate can be thought of as meaning "when qubit $C$ is Z-on, negate the amplitude of the Z-on state of qubit $T$". In that same language, a CNOT gate means "when qubit $C$ is Z-on, negate the amplitude of the X-on state of qubit $T$". Or, by speaking at the level of the whole system, we can say that the CZ gate means "negate the amplitude of the $|Z_1^{\text{on}} Z_2^{\text{on}}\rangle = |11\rangle$ state" whereas the CNOT gate means "negate the amplitude of the $|Z_1^{\text{on}} X_2^{\text{on}}\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|10\rangle - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|11\rangle$ state". That's why framing one qubit of a CZ with Hadamards turns the CZ into a CNOT.

Now let's think about axes besides X and Z.

Generalizing Xor-Swapping into Axis-Swapping

The CNOT operation negates the amplitude of the state $|Z_1^{\text{on}} X_2^{\text{on}}\rangle$, and leaves perpendicular states alone. As a suggestive shorthand, I'm going to write the CNOT operation as the expression $\text{CNOT}_{1 \rightarrow 2} = Z_1 \sim X_2$. The tilde is notation I just made up for this post; it means "combined in the way that makes one control the other". I'll be referring to the operation performed by the tilde operator as the "control-product".

To be mathematically precise, I define the control-product of two commuting unitary operations $A$ and $B$ to be $A \sim B = \exp(-\frac{i}{\pi} \ln(A) \cdot \ln(B))$. (Side note for physicists: Yes, I'm just multiplying the Hamiltonians together.) Interestingly, even though we started with an asymmetric concept (one operation controlling another), the math ended up symmetric. You can think of either operation as being "the control" of the other.

We can sanity-check the control-product definition by verifying that the CNOT operation's matrix is in fact the control-product of phase-flipping the control and toggling the target:

from scipy.linalg import expm, logm

from numpy import mat, pi, kron, eye

def control_product(A, B):

# Note: A and B must commute.

return expm(1j/pi * logm(A).dot(logm(B)))

I = eye(2)

X = mat([[0, 1],

[1, 0]])

Z = mat([[1, 0],

[0, -1]])

Z1 = kron(Z, I)

X2 = kron(I, X)

CNOT = control_product(Z1, X2)

print(CNOT.round().astype(int))

# [[1 0 0 0]

# [0 1 0 0]

# [0 0 0 1]

# [0 0 1 0]]

Yup, that's the matrix of a CNOT!

Now let's write our xor-swapping algorithm down, but in the language of the control product. It's pretty simple: the operations that xor-swapping applies are $Z_1 \sim X_2$ then $X_1 \sim Z_2$ then $Z_1 \sim X_2$. (Notice the alternating back-and-forth pattern.) That's it.

To be safe, we should check that multiplying those operations together returns the correct matrix:

Z1 = kron(Z, I)

Z2 = kron(I, Z)

X1 = kron(X, I)

X2 = kron(I, X)

Swap = control_product(Z1, X2).dot(

control_product(X1, Z2)).dot(

control_product(Z1, X2))

print(Swap.round().astype(int))

# [[1 0 0 0]

# [0 0 1 0]

# [0 1 0 0]

# [0 0 0 1]]

Yup, that's the swap matrix.

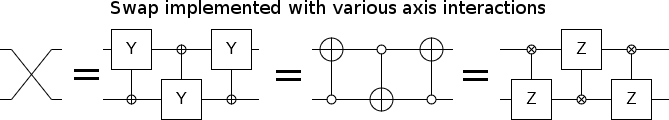

A natural question to ask here is: what happens if we use this alternating pattern on other axes of the qubit? Is xor-swapping specific to the X and Z axes, or does it work more generally?

Well... clearly it can't be specific to those two axes. The fact that we call one particular axis the Z axis (or "the computational basis") is just an arbitrary convention; a coordinate system. The underlying math is independent of our naming conventions, so this alternating technique must work in some sense no matter which axis we use.

Just to be sure, we can test in python if using X and Y instead of Z and X works:

Y = mat([[0, -1j],

[1j, 0]])

Y1 = kron(Y, I)

Y2 = kron(I, Y)

SwapXY = control_product(X1, Y2).dot(

control_product(Y1, X2)).dot(

control_product(X1, Y2))

print(SwapXY.round().astype(int))

# [[1 0 0 0]

# [0 0 1 0]

# [0 1 0 0]

# [0 0 0 1]]

Yup.

We can also test this in Quirk, which has support for X-axis and Y-axis controls:

Based on these quick tests, it would be reasonable to conclude that the alternating-control-product-interactions trick will perform a swap regardless of which axis pair we pick. However, there are some exceptions. In particular, if we pick two axes that aren't perpendicular to each other (e.g. X and the diagonal X+Z), then the swap doesn't work correctly.

The reason we need to use perpendicular axes comes down to the fact that the observables for those axes anti-commute. In some fundamental sense that I'm not going to try to explain, pairing the $X$ axis with the $Z$ axis works because their axis-flip operations $X=\bimat{0}{1}{1}{0}$ and $Z=\bimat{1}{0}{0}{-1}$ have an anti-commutator $\{X, Z\}$ that satisfies $\{X, Z\} = XZ + ZX = 0$ (i.e. we have $XZ = -ZX$).

Generally speaking, if the axis-flip operations $A$ and $B$ satisfy $\{A, B\} = 0$, then the operation $\text{AXIS_SWAP}^{A, B}_{i, j} = (A_i \sim B_j) \cdot (B_i \sim A_j) \cdot (A_i \sim B_j)$ is a swap operation between qubit $i$ and qubit $j$.

We've generalized from Xor-Swapping with CNOTs to a construction that can swap two qubits by back-and-forth interacting two qubits along any perpendicular pair of axes. But we're not done generalizing yet!

Generalizing Axis-Swapping into Observable-Swapping

What happens if we apply axis-swapping, but don't use the same axes for each qubit? For example, suppose we use the $X$ and $Z$ axes on qubit 1 but use the $Z$ and $Y$ axes on qubit 2? That is to say: we apply $X_1 \sim Y_2$ then $Z_1 \sim Z_2$ then $X_1 \sim Y_2$. What happens?

What happens is that the two qubits get swapped, but they also get rotated. If the first qubit had a state pointing along the $X$ axis, then once that state arrives on the second qubit it will be pointing along the $Z$ axis. Correspondingly, a $Z$-state on the second qubit will become an $X$-state on the first qubit. Instead of swapping $X_1$ for $X_2$, we're swapping $X_1$ for $Z_2$! (Also, we're swapping $Z_1$ for $Y_2$).

This suggests a way to define a more general swap operation. Given two pairs of observables, $(A_1, A_2)$ and $(B_1, B_2)$, if each pair anti-commutes (i.e. $\{ A_1, A_2 \} = 0$ and $\{ B_1, B_2 \} = 0$) and is independent of the other pair (i.e. their commutator $[A_k, B_k] = A_k B_k + B_k A_k$ satisfies $[A_k, B_k] = 0$), then:

$$\text{SWAP}^{A_1, A_2}_{B_1, B_2} = (A_1 \sim B_2) \cdot (A_2 \sim B_1) \cdot (A_1 \sim B_2)$$

is an operation that exchanges states along $A_1$ for states along $B_1$, and states along $A_2$ for states along $B_2$.

The amazing thing about this generalized definition is that it works for any observables. We can apply it to qubit axes, but we can also apply it to complicated multi-qubit properties. As long as $A_1$, $A_2$, $B_1$, and $B_2$ satisfy the correct commutation and anti-commutation relations, it'll work.

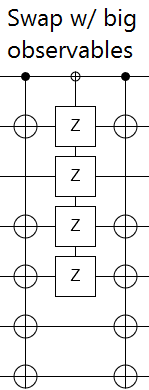

To demonstrate what that means, let's do an example. For $A_1$ and $A_2$ we will use the $Z$ and $X$ axes of qubit #1. But, for $B_1$ and $B_2$, we will use observables involving many qubits. Specifically, $B_1$ will be the $Z$-axis parity of qubits #2, #3, #4, and #5. (You measure this observable by preparing a target qubit in the $|0\rangle$ state, CNOT-ing each of the qubits into the target, then measuring the target.) $B_2$ will also be defined as the parity of several qubits, but it will be an X-axis parity and it will not use the same set of qubits. $B_2$ will be the X-axis parity of qubits #2, #4, #5, #6, and #7.

If you know how, you should check that the observables $A_1 = Z_1$ and $A_2 = X_1$ and $B_1 = Z_2 \cdot Z_3 \cdot Z_4 \cdot Z_5$ and $B_2 = X_2 \cdot X_4 \cdot X_5 \cdot X_6 \cdot X_7$ have the correct commutation and anti-commutation relationships. Based on that being correct, we can implement the $\text{SWAP}^{Z_1, \; X_1}_{Z_2 \cdot Z_3 \cdot Z_4 \cdot Z_5, \; X_2 \cdot X_4 \cdot X_5 \cdot X_6 \cdot X_7}$ operation like this:

We can check that this is actually working by moving a qubit into the big parity observables, then retrieving it. This should work even if we put all kinds of junk into the qubits used to define the parities. Here's what that looks like when simulated in Quirk:

Notice how the Bloch sphere display in the bottom right matches the display in the top left as it rotates around? That's because the qubit state from the top is being swapped into the middle and then into the bottom. (Even though the middle we passed it through is going kinda nuts. Actually, if you look closely, you can see at the end that we left some holes behind in the middle.)

This is pretty neat! We started with a single simple qubit, then moved its value into some big complicated observables amongst a bunch of junk, then managed to retrieve the value! This demonstrates a very important lesson: any pair of anticommuting observables can store a qubit. This fact is key to understanding many error correcting codes, which spread a single logical qubit over many physical qubits. And we can use the definition of our generalized swap operation to move qubits into, between, and out of these big complicated anticommuting observables.

Whew, I think we've generalized xor-swapping enough for one day! Let's look at a totally different approach to swapping.

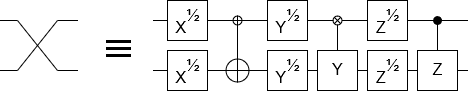

XYZ Swapping

It is a fact that any two-qubit operation can be decomposed into local single-qubit parts and one non-local operation of the form $\exp(i \pi (x X_1 X_2 + y Y_1 Y_2 + z Z_1 Z_2))$. Equivalently, we can split the non-local part of the operation into three commuting parts: an X-parity-phasing part $(X_1 X_2)^x$, a Y-parity-phasing part $(Y_1 Y_2)^y$, and a Z-parity-phasing part $(Z_1 Z_2)^z$. The size of the numbers $x$, $y$, and $z$ gives a measure for "how non-local" an operation is.

For the swap operation, the non-local parameters are $x=y=z=\frac{1}{2}$. Interestingly, this is the most non-local an operation can get. If we follow-up the swap with another operation, the "size" of the parameters can only get smaller. That's because, for example, once $z$ goes past the half-way mark it starts getting closer to the operation $(Z_1 Z_2)^1 = Z_1 Z_2$ (which is local). Anytime our parameters leave the $[-\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}]$ range, we can make their magnitude smaller by applying a $\pm 1$ offset to them with local operations.

If we want to perform a swap based on the non-local decomposition, we need to know how to implement operations like $(Z_1 Z_2)^z$. What the $(Z_1 Z_2)^z$ operation does is leave the $|00\rangle$ and $|11\rangle$ states alone, but phase the amplitudes of the $|01\rangle$ and $|10\rangle$ states by $(-1)^z$. When the two qubits agree on Z-value, nothing happens. When they disagree, that part of the superposition gets phased. It's the agreement-vs-disagreement of the two qubits, i.e. their parity, that controls the phasing. That's why I call it a Z-parity-phasing operation.

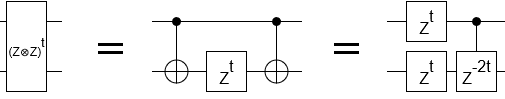

A simple way to compute this effect is to use a CNOT to compute the parity, apply a $Z^z$ operation to the qubit storing the parity, then uncompute the parity. Another way to compute the effect is to apply a $Z^{z}$ operation to each qubit, then correct the fact that we phased the $|11\rangle$ state by $Z^{2z}$ with a controlled operation in the opposite direction. Both are equivalent to the desired operation:

By creating analogous circuits for the XX and YY interactions, then chaining all three axis-parity effects together, we get a swapping circuit that at least looks qualitatively different from xor-swapping:

The X, Y, and Z parts can be placed in any order. As long as the single-qubit gates are adjacent to the 2-qubit gate with a corresponding axis, it'll work.

Note that the XYZ construction above is correct up to global phase (the RHS of the above diagram has an addition global phase factor of $i$). If you want to apply a controlled-swap, this causes phase kickback that has to be corrected (e.g. with an $S^\dagger$ gate on the control).

Specializing the XYZ Swap

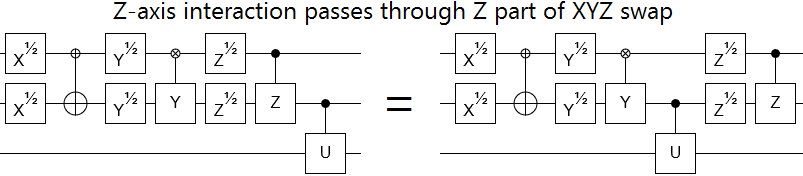

Consider that Z-axis interactions commute with the Z-parity part of the XYZ swap construction:

This means that the thing that moves the Z-axis interaction from one wire to the other must be just the XY part. So, if we happen to be in a situation where we only have the XY part of an XYZ swap, it's still possible to move Z-axis operations across. Z-axis interactions still move to the other wire when the Z part of an XYZ swap is missing:

However, moving an X-axis interaction across a swap with only its XY part doesn't work. For that to work, we need the Y part and the Z part; the X part doesn't matter to X axis interactions.

In other words, as far as moving operations is concerned, we can specialize an XYZ swap to a specific axis by dropping the part of the XYZ swap corresponding to that axis. Operations along that axis will still get moved to the other wire when you pass them through the reduced swap.

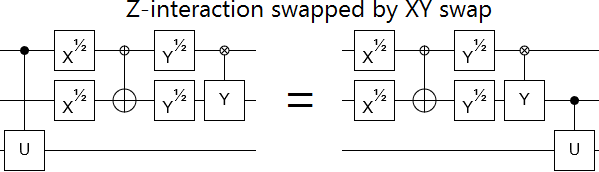

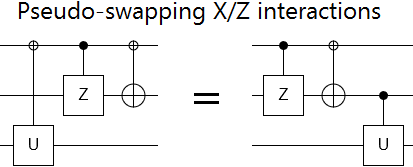

There's another interesting specialization that occurs when we drop even more of the swap. If we drop one of the axis interactions, and then drop all of the single-qubit gates, we end up with an operation like $Z_1 \sim Z_2$ then $X_1 \sim X_2$:

The interesting thing about this circuit is that an X axis interaction on one wire after the circuit is equivalent to a Z axis interaction on the other wire before the circuit. But the same is not true in reverse. You can move Z-axis interactions from left to right over the circuit in a nice way (just swap the wire and switch an X axis interaction), but when you go from right to left complicated stuff happens instead.

This one-way-okay phenomenon is analogous to the fact that removing the first CNOT of a xor-swap will cause the swap to only work properly in one direction. But now I'm in danger of retreading information on xor-swapping, so I'll leave figuring out how the two relate as an exercise for the reader and move on.

Far-Swap

What if the two qubits you want to swap aren't next to each other?

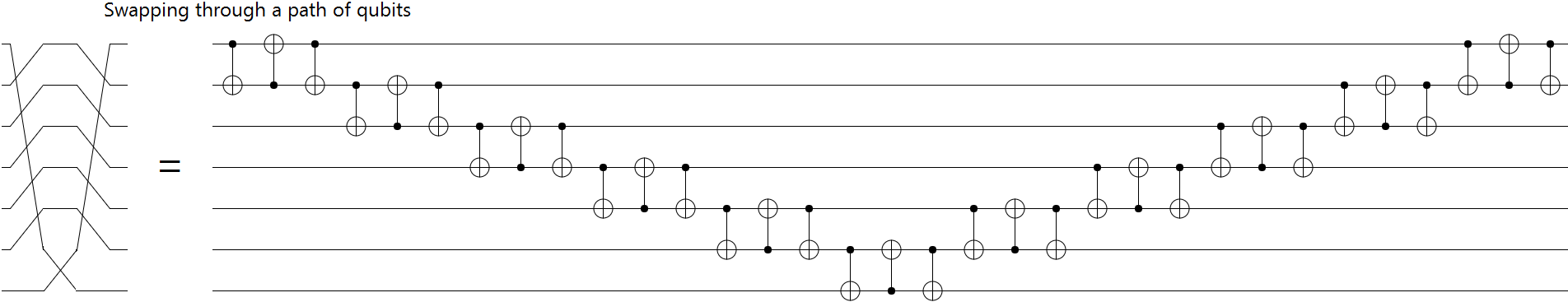

Well, if there's a path of connected qubits between them then you can swap one towards the other until they're adjacent, do the important swap, then return to the starting position. Break the swap chain down into CNOTs, and you get this:

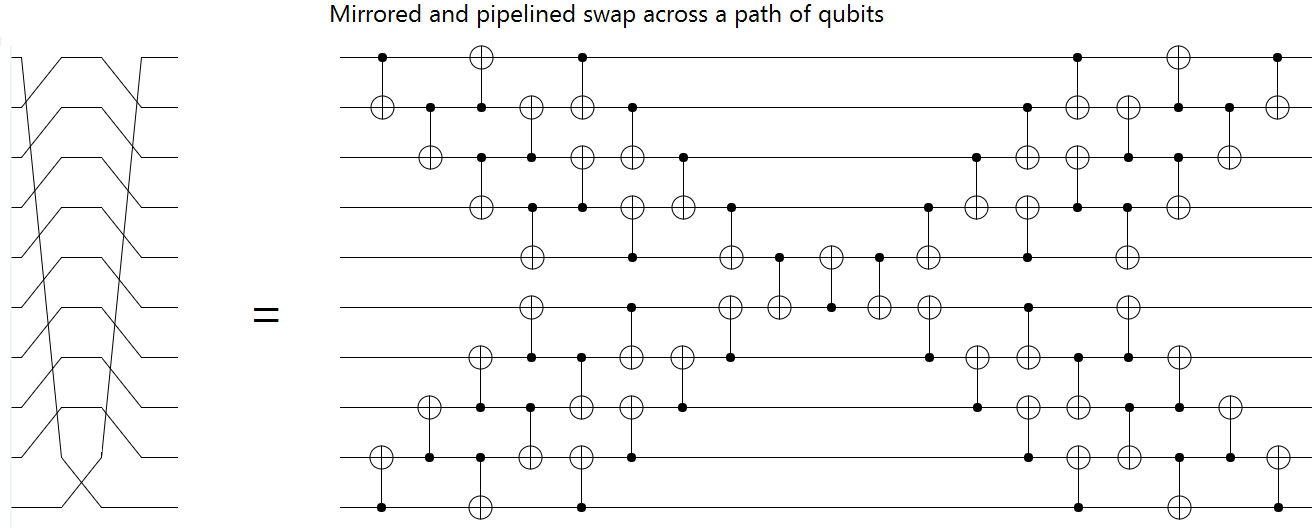

The above construction is not very efficient. It has depth $6D + O(1)$, where $D$ is the distance between the two qubits you want to swap. We can do much better than that! We can cut a factor of 2 by meeting in the middle, and a factor of three by pipelining the intermediate xor-swaps in a clever way. The result is a distance-$D$ swap with depth $D + O(1)$:

Much better.

Although... we are still assuming there's a path between the two qubits. What if that's not the case?

...Well then you're pretty well stuck, unless you have some source of shared entanglement.

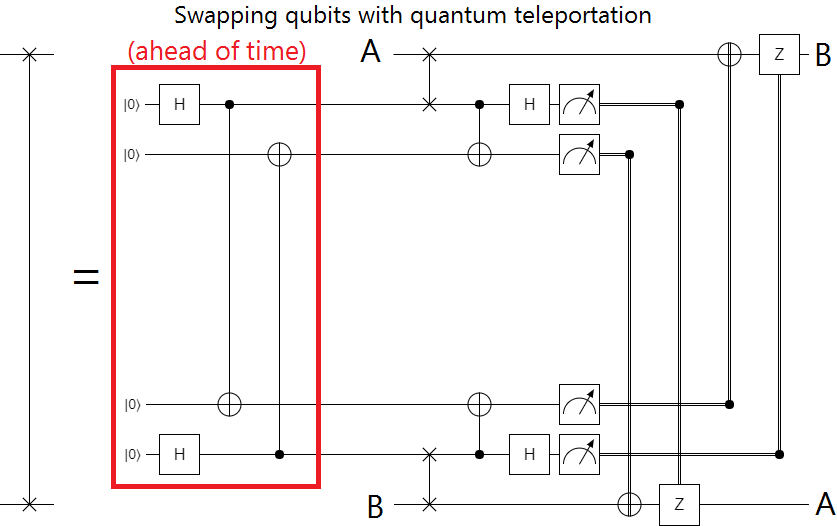

If you have some mechanism for building up entanglement in your two disconnected components, then you can use that entanglement to swap the two qubits with quantum teleportation. Here's what the circuit to do that looks like:

I would go into detail about how this works, but honestly it's just two quantum teleportations shoved together and this post is already way too long. I think I've said enough for today.

Summary

There's more than one way to break down a swap.

Any pair of anti-commuting observables can store a qubit of information. You can use observable swapping to store/retrieve that information.

When you remove pieces of a swap, some axis interactions may still switch wires when moving across the swap.

Even qubits isolated into different machines can be swapped, if you can build up entanglement between the two locations.

There's an awful lot to say about such a basic operation.