In this post, I'm going to explain a trick for phasing quantum states in a convenient and flexible way. Basically, the trick involves preparing ancilla qubits to act as proxies for the states you want to target, then phasing those ancilla. Thus the name "proxy phasing".

We'll start simple, but by the end of the post we'll be phasing each state by an arbitrary computable function of that state.

Proxy-phasing one qubit

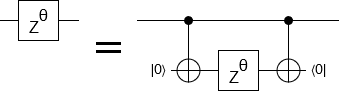

As promised, let's start with something simple; maybe even trivial. Instead of phasing a qubit directly, we can temporarily CNOT it onto a clean ancilla and phase the ancilla:

If you pay attention to the bit values that define the computational basis states, and understand that a Z gate on a qubit phases any states where the corresponding bit is 1, it's clear why phasing the ancilla is phasing the original qubit. Here's what happens:

- The system starts in the state $a |0\rangle + b |1\rangle$.

- We introduce the ancilla, producing the state $(a |0\rangle + b |1\rangle) \otimes |0\rangle$, or equivalently $a |00\rangle + b |10\rangle$.

- We apply the first CNOT, transitioning to the state $a |00\rangle + b |11\rangle$. Notice that the first bit always agrees with the second bit.

- We apply the Z gate. This applies a phase factor to states where the qubit is 1. If we apply the Z gate to the first qubit, it phases the $|11\rangle$ component because the first bit of that component is 1. If we apply the Z gate to the second qubit, it phases the $|11\rangle$ component because the second bit of that component is 1. Neither of the two locations would phase the $|00\rangle$ component, because that component's bits aren't 1. The location of the Z gate does affect whether the $|01\rangle$ and $|10\rangle$ components would be phased, but those components aren't present in the state we're operating on. The two possible Z operations have the same effect on the components that are present, therefore they are equivalent. Whether we target the original qubit or the ancilla qubit, we find ourselves in the state $a |00\rangle + (-1)^t b |11\rangle$.

- We uncompute the ancilla by applying the second CNOT. This leaves us in the state $a |0\rangle + (-1)^t b |1\rangle$, which is what we wanted.

In general, if two qubits are guaranteed to agree, then you can move a Z gate from one to the other without changing the function of a circuit. ("Guaranteed to agree" is a bit vague. What I mean is that, if you were to do a computational basis measurement of the two qubits at the relevant time, there is no chance the measurement results would disagree. CNOT-ing a qubit onto a clean ancilla is the simplest way to create such a state.)

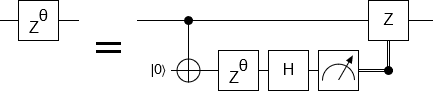

Note that we can uncompute the ancilla qubit with entanglement erasure instead of with a second CNOT:

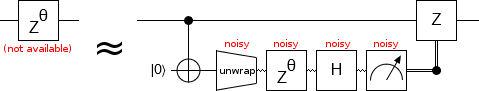

The above equivalence is a key part of magic state distillation. For example, the surface code is a quantum error correcting code that's not normally able to apply T gates (i.e. 45 degree rotations around the Z axis). But you can CNOT a surface-coded qubit onto a clean surface-coded ancilla qubit, unwrap the ancilla into a raw physical qubit where 45 degree rotations are possible, and do the phasing there:

Other techniques are used to remove the noise caused by using a non-error-corrected qubit. Still, the realization "Oh, that's proxy phasing" is a solid opening move for understanding magic state distillation.

Proxy-phasing combinations of qubits

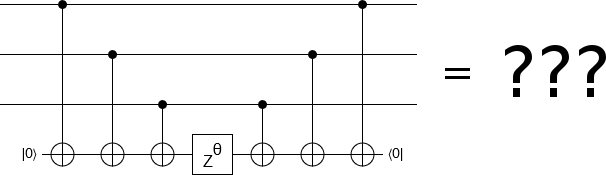

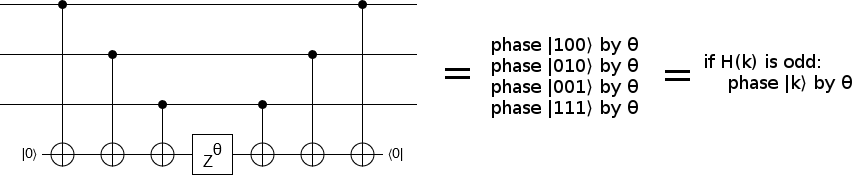

Suppose that we CNOT multiple qubits onto a single clean ancilla, then phase the ancilla. What happens?

To answer this question, we ask another: if this was a classical circuit, what states would lead to the ancilla bit being ON?

Well, each CNOT may or may not toggle the ancilla bit. If there's an odd number of toggles, the ancilla bit will end up ON. If there's an even number of toggles, the ancilla bit will end up OFF. And our circuit toggles the ancilla bit once for each input bit that's ON... Therefore the ancilla bit will be ON if the input state has an odd number of set bits.

Now back to the quantum case. All of the operations that are present permute the computational basis without mixing (interfering) any of its elements (e.g. there are no Hadamard operations). Because of this fact, we can basically directly apply what we learned when considering the classical case. For computational basis states with an odd number of set bits, the ancilla qubit ends up ON. For the other states, it ends up off. For example, the input state $a |000\rangle + b|010\rangle + c|011\rangle$ will expand into the intermediate state $a |000\rangle|0\rangle + b|010\rangle|1\rangle + c|011\rangle|0\rangle$.

Speaking a bit more abstractly, the three CNOTs transition the system from the state $\sum_k w_k |k\rangle$ to the state $\sum_k w_k |k\rangle |P(k)\rangle$, where $P$ is a parity function that determines whether $k$'s Hamming weight $H(k)$ is odd or even. It is reasonable to describe this situation as "the ancilla qubit is storing the parity of the other three". So, when we phase the ancilla, we are phasing that parity. States where the parity is 1 get phased, and states where the parity is 0 don't get phased.

This concept generalizes. To phase the set of states matching a predicate $P^\prime$, you compute $P^\prime$ and store the result into an ancilla $A$, then phase $A$ by the desired amount, then uncompute $P^\prime$. Any set whose membership can be computed can be phased in this way. The easier it is to compute a set, the easier it is to phase that set.

For example, suppose you're using Grover's algorithm to search for variable assignments that satisfy a 3-SAT problem. This requires you to apply a phase factor of -1 to all of the satisfying variable assignments. But... how can you phase the very thing you're looking for, without already knowing where it is? That's where proxy phasing comes in. Apply a reversible circuit that outputs whether the inputs are a satisfying assignment to the problem, apply a Z gate to the output qubit, uncompute the circuit, and you've done it!

Remember: to phase a specific set of states, all you need is a function that recognizes that set.

Phase gradients

Being able to construct a nice circuit for phasing a set of states is great, but often you'll want more fine-grained control than just phase-or-not-phase.

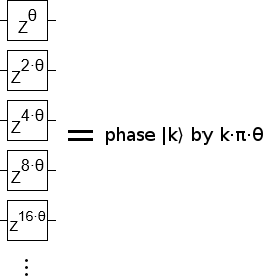

In particular, suppose we want to phase each computational basis state $|k\rangle$ by $k \cdot c$ radians for some constant $c$, such as $c = \frac{\pi}{1000}$. (I call this kind of operation a "phase gradient" or "linear phase gradient".) This task is actually quite simple, because of the binary-to-unary relationship between the qubits and the state indices. Assuming the qubits are in little-endian order from top to bottom, we simply phase the top qubit by $\frac{\pi}{1000}$ radians, the next qubit by $\frac{2 \pi}{1000}$ radians, the next by $\frac{4 \pi}{1000}$ radians, and so forth until the bottom ($n$'th) qubit is phased by $\frac{2^{n-1} \pi}{1000}$:

To understand why this works, consider the state $|01011\rangle$. 01011 is eleven in binary, so we want to phase this state by $\frac{11 \pi}{1000}$. When we phase a qubit, the $|01011\rangle$ state is phased if and only if it has a 1 at that qubit's position. In this case, the state will be affected by phasing applied to the first, second, and fourth qubits but not by phasing applied to other qubits. If we combine the phasings effects from the first, second, and fourth qubits we get $\frac{1 \pi}{1000} + \frac{2 \pi}{1000} + \frac{8 \pi}{1000}$. Which is equal to $\frac{11 \pi}{1000}$, which is what we wanted.

The reason this works is because we're matching the phasing of each qubit to its weight in our binary encoding of numbers. The fourth bit of a binary number has a weight of $2^3$ (turning it on increases the represented number by 8), and so we scale the phasing effect by 8. The weights of the set bits add up to the number we want to represent, and the phasing effects add up in exactly the same way.

Now that we have phase gradients, we can start using them on proxy qubits.

Computed phasing

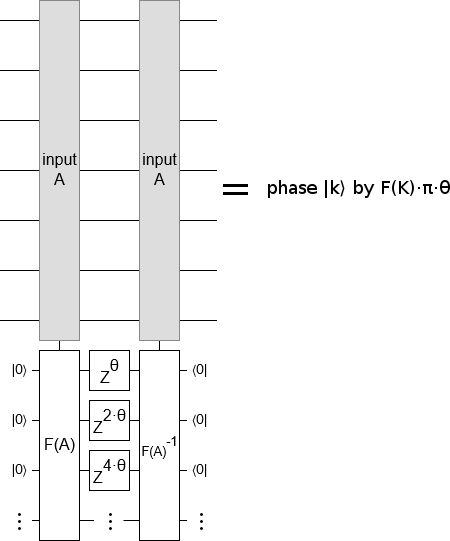

Suppose we want to phase each state $|k\rangle$ by some function $F$ of $k$ that isn't of the form $F(k) = c \cdot k$. For example, suppose we want to phase each computational basis state $|k\rangle$ by $F(k) = k^2 \frac{\pi}{50}$ radians. Can we construct a reasonable circuit to do that? Yes we can! And, as you might guess based on the content so far, the trick involves a circuit that computes the function we're interested in phasing by.

We want to phase by an amount proportional to $k^2$, so the first thing to do is construct a classical reversible circuit to compute the square of an input. Second, use this circuit to store the input's square into an ancilla register. Third, apply a phase gradient to the ancilla register. Lastly, uncompute the ancilla register.

To phase by a different function, replace squaring with any other computable function $F$:

Keep in mind that the phase gradient can absorb pesky constant factors. Also keep in mind that, for most choices of $F$, you will want to compute an approximation rather than an exact result. The result must be stored in fixed point arithmetic, not floating point arithmetic, for the phase gradient construction to make sense.

Applications

The fact that you can phase by any computable function is useful to keep in mind. For example, consider a circuit that rotates $N$ qubits by $\theta$ radians. This effect is so simple that you might assume it is impossible to optimize beyond just applying an $R_Z(\theta)$ gate to each qubit. But, knowing about computed phasing, you may feel prompted to ask: what's the function that this circuit is applying to the state? Is there a fast way to compute that function?

Consider the state $|011001\rangle$. How much is this state phased by applying $R_Z(\theta)$ to every qubit? The $R_Z(\theta)$ operation doesn't phase 0s, but phases 1s by $\theta$. The state $|011001\rangle$ has three ones, so it will be phased by $\theta$ three times totalling $3 \theta$. Other states follow the same rule: the number of set bits determines how much phasing happens. State $|k\rangle$ will be phased by $F(k) = \theta \cdot H(k)$, where $H$ is the Hamming weight function

Okay, so instead of rotating the $N$ qubits individually we can make a circuit that computes the Hamming weight of the qubits (i.e. adds them all together), apply a phase gradient to the $\lg N$ qubits making up the Hamming weight register, then uncompute the register. Surprisingly, when performing error corrected computation, this can be cheaper than applying the individual rotations! Arbitrary rotations by some $\theta$ have to be synthesized by combining a fixed set of available rotations, with the dominant cost being the number of $T$ gates (45 degree rotations around Z). As your desired accuracy $\epsilon$ gets smaller, more and more T gates are required. It can take dozens of T gates to synthesize a good-enough rotation! By contrast, temporarily counting up $n$ qubits takes roughly 4 T gates per qubit (see my paper Halving the cost of quantum addition).

Suppose it takes $m$ T gates to synthesize one accurate-enough rotation. The cost of individually rotating all $n$ qubits would be $m \cdot n$, but the cost of counting up the bits and applying a phase gradient is $4n + m \cdot \lg n + O(\lg n)$. Even if $m$ is 20 and $n$ is 3, this reduces our T-count from 60 to 44. As $m$ and $n$ get larger, the savings start becoming very big very fast. Surprisingly, this means that there's no "really hard angle" $\theta_{\text{hard}}$ where synthesizing many rotations by $\theta_{\text{hard}}$ is arbitrarily more expensive than synthesizing the same number of T gates. The phase-by-count construction guarantees that performing many rotations by any single $\theta$ always limits to at most 4 times as expensive as a T gate.

Computed phasing is also interesting from a programming language design perspective. For example, it allows the quantum Fourier transform to be written very succinctly:

def apply_qft(register):

apply reverse to register

for k, q in enumerate(register):

phaseby q * register[:k] * pi/2**k

apply H to q

But I digress.

Summary

Any computable phasing function can be applied with the cost of merely computing and uncomputing that function. (The same is not true for magnitudes. Exercise: why?)

If you want to phase a specific set of states, make a circuit that temporarily computes membership in that set and applies a Z gate to that computation's output. If you want to phase each state by an amount determined by a function, make a circuit that temporarily computes a fixed-point register proportional to the function's output and applies a phase gradient to the output register.

When phasing qubits, consider how the underlying states are being phased. Is there an easy-to-compute function that picks out the affected states, or that determines how much each state is phased by? If so, computed phasing may be more efficient than a naive construction.