Recently I read the blog post "The Trouble with Many Worlds". I liked the post, but I always find it a bit strange reading this kind of content. People seem so very philosophically upset/confused/fascinated by "the measurement problem" and the Born rule, but I have to admit that deep down I've never found this problem compelling. Every physical model needs some kind of mapping from abstract symbol land into concrete action-and-expectation land, and when you look at the other postulates of quantum mechanics (mainly unitarity) the form that this mapping is going to have to take seems pretty clear.

Anyways, I realize that this sense of "of course it will take that form" is ultimately subjective, and that there are subtle philosophical issues here. I also realize that I am not nearly the first person express the sentiment that the Born rule appears intrinsic to the structure of quantum mechanics. For example, David Deutsch has papers proving that, given some sort of rationality constraint, agents embedded into quantum mechanical systems are forced to use the Born rule. But I still want to try to explain in my own terms where this sense I get, that if you have unitary of course you're going to have the Born rule, comes from.

The argument that I will make is going to take a pretty typical form. I'll pick a few assumptions that I think are "an easier sell" than the Born rule, and then show that the Born rule is a practical consequence.

Axioms / assumptions / definitions

You can't prove anything without defining your terms or saying which axioms are allowed. I have attempted to choose a "reasonable" set of assumptions, though I do realize that readers' preferences will vary. Here are the otherwise-unjustified things which will be needed by the argument I am going to make:

- Standard representation. A quantum state is a unit vector in $\mathbb{C}^{N}$. a quantum operation is a unitary matrix from $\mathbb{U}(N)$. Qubits and quantum gates such as the Toffoli are defined in terms of these representations in the usual way.

- Compatible certainty. As the amplitude of a computational basis state approaches 1, the probability of a computational basis measurement returning that state as a result must also approach 1.

- No signalling. The measurement outcome probabilities for a qubit are unaffected by unitary operations on other qubits.

- Compatible computation. A concept defined in terms of a reversible classical circuit can be generalized into the quantum context via the quantum behavior of the same circuit.

- Frequentist probability. When I say "the process $f$ has probability $p$" I mean that the following computation will usually produce a positive result: perform $f$ many times, count up the number of positive results, divide the count by the number of samples, and check if that produced a value near $p$.

The most important thing in the above list is the definition of what is meant by the term probability, so let's lay that out in more detail. We need to define some notion of a sample rate $k/n$ being "near" a hypothesized rate $p$. The main subtlety is how near is near enough. We'll use a maximum distance of $n^{-1/3}$ from the true rate, because this expression is pretty simple and ensures that the expected number of false positives and false negatives (when applying this definition to random sampling) will limit to 0 as $n$ goes to infinity:

$$ \text{RateNear}(k, n, p) = \Big( |k/n - p| < n^{-1/3} \Big) $$

The above check only achieves perfect precision in the infinite limit, so it's important to have that concept available:

$$ \text{RateApproaches}(f, p) = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \text{RateNear}(\text{CountPositiveSamples}(f, n), n, p) $$

And now we can properly define the true rate of $f$ (assuming the underlying limits exist):

$$ \text{Rate}(f) = \text{argmax}_p \; \text{RateApproaches}(f, p) $$

(The argmax is being used to find the unique value of $p$ that makes the rate-approaches predicate return 1 (True) instead of 0 (False).)

When I say "$f$ has probability $p$", you should interpret that as meaning $\text{Rate}(f) = p$ and nothing else. That's not because I think quantum mechanics is incompatible with e.g. the Bayesian concept of probability; I'm just trying to keep this post focused.

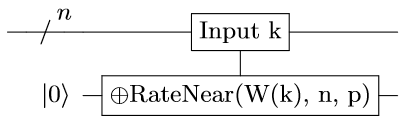

In order to generalize this frequentist definition of probability to the quantum domain, we have to operationalize it into a concrete reversible classical circuit. For example, the circuit could have a counter and for each sample the circuit would increment the counter conditioned on that sample. The circuit would then check if the counter was close enough to the expected value and, if so, toggle an output bit. The counter would then be uncomputed by conditionally decrementing it for each sample. The details here aren't particularly important; what matters is that there is some circuit that implements the is-rate-near check:

where $W(k)$ is the Hamming Weight of the integer $k$; the number of 1s in $k$'s binary representation.

The above circuit, which I will refer to as $C_{n,p}$, is a computational definition of $\text{RateNear}$. The limiting behavior, when considering a series of larger and larger such circuits, matches what we mean by probability classically. Our goal is to apply the compatible computation assumption to generalize this definition of probability into the quantum domain, and determine what it tells us about the rate of $f$ when $f$ is a quantum process such as "prepare the state $|\psi\rangle = \cos \theta |0\rangle + \sin \theta |1\rangle$".

Quantum behavior of the probability definition circuit

Quantumly, the action of $C_{n,p}$ on a computational basis state $|k\rangle$ is:

$$ C_{n,p} |k\rangle|0\rangle = |k\rangle|\text{RateNear}(k, n, p)\rangle $$

Or, across an entire wavefunction:

$$ C_{n,p} \sum_{k=0}^{2^n-1} \sum_{b=0}^1 \lambda_{k,b} |k\rangle|b\rangle = \sum_{k=0}^{2^n-1} \sum_{b=0}^1 \lambda_{k,b}|k\rangle|b \oplus \text{RateNear}(k, n, p)\rangle $$

To make it easier to describe what comes out of $C_{n,p}$ when we input many copies of $|\psi\rangle = \cos \theta |0\rangle + \sin \theta |1\rangle$, we need a few bits of notation.

The set of integers of bit length $n$ with Hamming weight $w$ is written like this:

$$\left\{ n \atop w \right\} = \{k \in [0, 2^n) | W(k) = w\}$$

The sum of all computational basis states kets with Hamming weight $w$ is written like this:

$$ \left| n \atop w \right\rangle = \sum_{k \in \left\{ n \atop w \right\}} |k\rangle $$

With this notation, the input state can be rewritten into the following form:

$$\begin{aligned} \text{input} &= |\psi\rangle^{\otimes n}|0\rangle \\&= (\cos \theta |0\rangle + \sin \theta |1\rangle)^{\otimes n} |0\rangle \\&= \sum_{w=0}^n \cos^{n-w} \theta \sin^w \theta \left| n \atop w \right\rangle |0\rangle \end{aligned}$$

We can then very easily write down the result of applying $C_{n,p}$ to this state:

$$\begin{aligned} \text{output} &= C_{n,p} \cdot \text{input} \\&= C_{n,p} \sum_{w=0}^n \cos^{n-w} \theta \sin^w \theta \left| n \atop w \right\rangle |0\rangle \\&= \sum_{w=0}^n \cos^{n-w} \theta \sin^w \theta \left( C_{n,p} \left| n \atop w \right\rangle |0\rangle \right) \\&= \sum_{w=0}^n \cos^{n-w} \theta \sin^w \theta \left| n \atop w \right\rangle |\text{RateNear}(w, n, p)\rangle \end{aligned}$$

In order to make the output state even more convenient to work with, we will rewrite it into the form $|v_0\rangle|0\rangle + |v_1\rangle|1\rangle$. The parts $|v_0\rangle$ and $|v_1\rangle$ just limit the iteration variable $w$ to the non-accepting and accepting ranges respectively:

$$\begin{aligned} |v_0\rangle &= \sum_{w=0}^{\lceil np-n^{2/3} \rceil-1} \cos(\theta)^{n-w} \sin(\theta)^{w} \left| n \atop w \right\rangle \\&+ \sum_{w=\lfloor np + n^{2/3} \rfloor+1}^{n} \cos(\theta)^{n-w} \sin(\theta)^{w} \left| n \atop w \right\rangle \end{aligned}$$

and:

$$ |v_1\rangle = \sum_{w=\lceil np-n^{2/3} \rceil}^{\lfloor np + n^{2/3} \rfloor} \cos(\theta)^{n-w} \sin(\theta)^{w} \left| n \atop w \right\rangle $$

Note that, currently, our output state has amplitude spread over many computational basis states. We need to fix this, because otherwise we will not be able to apply the compatible certainty axiom. The way we do so is by applying the no signalling axiom to send $|v_0\rangle$ and $|v_1\rangle$ to individual computational basis states.

Because $|v_0\rangle$ is orthogonal to $|v_1\rangle$, there is a unitary operation $U$ such that $U|v_0\rangle = \sqrt{\alpha} |0\rangle^{\otimes n}$ and $U |v_1\rangle = \sqrt{\beta} |1\rangle^{\otimes n}$. Because unitary operations preserve the 2-norm, we know that $\alpha + \beta = 1$ and that $\beta$ is determined by the 2-norm of $|v_1\rangle$:

$$\begin{aligned} \beta &= \langle U v_1 | Uv_1 \rangle \\&= \langle v_1 | v_1 \rangle \\&= \sum_{w=\lceil np-n^{2/3} \rceil}^{\lfloor np + n^{2/3} \rfloor} {n \choose w} (\cos^2 \theta)^{n-w} (\sin^2 \theta)^w \\&= \sum_{w=\lceil np-n^{2/3} \rceil}^{\lfloor np + n^{2/3} \rfloor} \text{Binomial}(n, w, \sin^2 \theta) \end{aligned}$$

By the properties of the binomial distribution, this sum limits to 1 as $n$ goes to infinity if and only if $p=\sin^2 \theta$:

$$\begin{aligned} \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \beta &= \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{w=\lceil np-n^{2/3} \rceil}^{\lfloor np + n^{2/3} \rfloor} \text{Binomial}(n, w, \sin^2 \theta) \\&=\begin{cases} p=\sin^2 \theta &\rightarrow 1 \\ p\neq \sin^2 \theta &\rightarrow 0 \end{cases} \\&= (p \stackrel{?}{=} \sin^2 \theta) \end{aligned}$$

And then via $\alpha + \beta = 1$ we get:

$$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty}\alpha = (p \stackrel{?}{\neq} \sin^2 \theta)$$

And now we have enough information to determine the behavior of the output state, after applying $U$, in the large $n$ limit:

$$\begin{aligned} \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty}U \cdot C_{n,p} \cdot |\psi\rangle^{\otimes n}|0\rangle &= \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \alpha |0\rangle^{\otimes n+1} + \beta |1\rangle^{\otimes n+1} \\&= (p \stackrel{?}{\neq} \cos^2 \theta)|0\rangle^{\otimes n+1} + (p \stackrel{?}{=} \cos^2 \theta)|1\rangle^{\otimes n+1} \end{aligned} $$

In other words, if the correct $p$ is being used (i.e. $p=\sin^2 \theta$), then as $n$ becomes larger and larger the amount of amplitude in the all-1s state will approach 1. Otherwise the amplitude in the all-0s state will approach 1. We have managed to encode into the output state, with high fidelity, information about what the probability associated with the process that produces copies of $\cos \theta |0\rangle + \sin \theta |1\rangle$ must be.

Therefore Born

By compatible certainty, limiting-to-1 behavior of amplitudes implies the same limiting-to-1 behavior in measurement probabilities. As $n$ increases, the amplitude of the positive result state (after applying the probability definition circuit to $n$ copies of $\cos \theta |0\rangle + \sin \theta |1\rangle$ and also the fixup unitary $U$) limits to 1 when $p$ is set to $\sin^2 \theta$ and limits to 0 otherwise. Therefore the probability of getting a positive result when performing this process and then measuring the output bit limits to 1 when $p$ is set to $\sin^2 \theta$ and limits to 0 otherwise.

By no signalling, the application of $U$ can be removed without affecting the result probability (because $U$ acts on qubits that aren't the qubit we are measuring). Therefore when we apply just the probability definition circuit to $n$ copies of $\cos \theta |0\rangle + \sin \theta |1\rangle$, the probability of getting a positive result limits to 1 if $p=\sin^2 \theta$ and otherwise limits to 0.

By compatible computation this behavior of the probability definition circuit implies that the probability-of-getting-1 of the state $\cos \theta |0\rangle + \sin \theta |1\rangle$ is ...(insert drum roll)... $\sin^2 \theta$! In other words, probabilities are determined by the Born rule.

Summary

If you assume a few "obvious" things about measurement (i.e. no signalling and compatible certainty), and you like your definitions of abstract concepts to cash out in terms of the results of physical experiments (i.e. you assume compatible computation and frequentist probability), then the Born rule is a natural consequence of the unitarity of quantum mechanics.