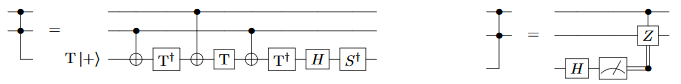

Often, when uncomputing intermediate values produced during a quantum computation, it is possible to save resources by using measurement operations in ways that don't work when computing those values in the first place. For example, computing the AND of two qubits requires non-stabilizer operations such as T gates, but you can get rid of an AND result using only stabilizer operations:

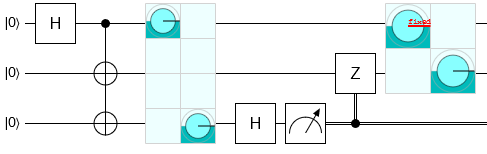

Another example is entanglement erasure. When limited to local quantum operations and classical communication (the LOCC regime), it is impossible to establish entanglement between parties. And yet, under LOCC it is possible to cleanly and selectively disentangle parties. For example, three parties sharing a GHZ state can eject any one of the qubits from the state such that the remaining two form an EPR pair:

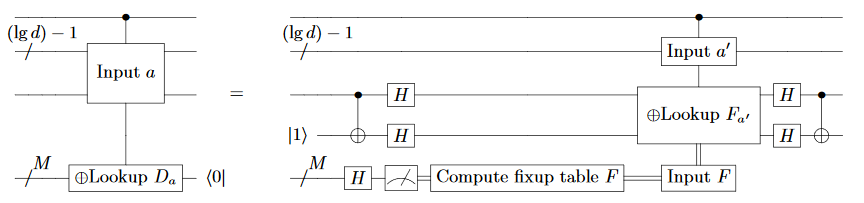

Yet another example is my contribution to the paper "Qubitization of Arbitrary Basis Quantum Chemistry Leveraging Sparsity and Low Rank Factorization" by Berry et al, which you can find in Appendix C. I figured out a method for cleaning up a QROM read (a table lookup) using significantly fewer non-stabilizer operations than are needed to compute the read. The method works by performing an X basis measurement of each of the looked-up qubits, figuring out which entries in the table toggled an odd number of the qubits that reported a True measurement result, and then phase-flipping the addresses of those entries by using a smaller table lookup:

That last example brings us nicely into what I want to discuss in this post. As you can see, the above circuit is a bit complicated; it has a lot of details. So I wanted to verify that it works correctly. But when I tried to implement it in Q# in order to verify it, I ran into an obstacle.

Problem

Q# has two different simulators: a state vector simulator and a Toffoli simulator. The state vector simulator can handle arbitrary quantum operations, but the cost of simulating each operation grows exponentially with the number of qubits. The Toffoli simulator is much much faster, needing only constant time per operation, but it only allows classical reversible gates such as the CNOT gate and the Toffoli gate. Generally speaking, the speed advantage of the Toffoli simulator is so great that you want to avoid operations that prevent you from using it.

Measurement Based UnComputation (hereafter MBUC), such as the lookup uncomputation and the AND uncomputation that I mentioned, almost always start by measuring qubits in the X basis. X basis measurement is not a classical operation. Therefore MBUCs are incompatible with Q#'s Toffoli simulator. This is problematic, because MBUCs are often subroutines useful in larger computations (consider: how often do you use an AND gate?). If you start introducing MBUCs into your code base, you will soon find that you aren't able to simulate anything efficiently anymore. This forces an apparent tradeoff: give up the ability to simulate (and thus verify) your code, or else give up the ability to achieve optimal resource counts. Neither choice is particularly appealing.

Solution

I spent a lot of time thinking about this problem and, eventually, came up with what I think is a pretty elegant solution. In order to explain it, I first need to explain the effect of X basis measurements at the start of an MBUC.

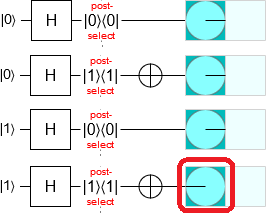

Suppose we are in a computational basis state (which is always the case for a Toffoli simulator). We measure a qubit in the X basis, and then reset the qubit to the 0 state by applying a Hadamard and then bit-flipping the qubit depending on the measurement result. What is the overall effect of this process? It's actually surprisingly simple. In all cases the qubit will be forced into the 0 state but, additionally, in exactly the case where the qubit was in the 1 state and the X basis measurement returned True, the phase of the computational basis state gets negated:

It may seem that we don't have to care about this phasing effect, because phase is irrelevant when not in superposition. But the only reason we're not in a superposition state is because we're testing in situations compatible with the Toffoli simulator. In practice these circuits would of course be applied to states under superposition (otherwise you wouldn't need a quantum computer), and in those cases this phasing effect is important and must be accounted for. Since none of the computational basis phases are negated when performing a normal uncomputation, the same must be true of a correct MBUC. For an MBUC to be correct, it is necessary and sufficient that it perform phasing operations that correct the probabilistic phase flips introduced by the X basis measurements.

So here is a simple way to test whether an MBUC is functioning correctly, without having to resort to a full state vector simulation. All you need to do is check that, for the given computational basis state that we happen to be in, and for the given random X basis measurements we happened to generate, that the MBUC cancelled out the phase flips caused by the X basis measurements.

As long as every MBUC declares where it starts and ends, and as long as the Toffoli simulator keeps track of the phase of the state (e.g. when an S gate is applied to a qubit that is ON the state's phase should be rotated 90 degrees), the Toffoli simulator can simulate MBUCs and automatically flag when an MBUC performs an incorrect phase fixup.

Assuming X basis measurement results are generated at random, any time we run a simulator performing this check we are essentially randomly sampling possible fixup cases and verifying that they are correct. We are fuzzing the MBUC. This fuzzing approach is sufficient for most purposes, but it would be a good idea to allow unit tests control over the pattern of simulated X basis measurements in order to guarantee that particular corner cases are hit.

Adding MBUC simulation and verification to Toffoli simulators is a clear win. It allows the Toffoli simulator to handle more gates, and fixes a nasty tradeoff between simulation efficiency and quantum gate count efficiency.

Summary

Toffoli simulators can efficiently test measurement based uncomputation constructions by tracking phase information and confirming that phase flips introduced by X basis measurements at the start of an MBUC have been cancelled out by the end of the MBUC.

I opened an issue on the Q# github repository and explained the MBUC simulation strategy there, so hopefully it will be added in a future version.

I have tested out the MBUC verification idea in my work-in-progress quantumpseudocode project, and so can report with confidence that it is good at catching dumb mistakes.