Last year, Frauchiger and Renner published the paper "Quantum theory cannot consistently describe the use of itself". The paper describes a paradox of reasoning, where deductions involving rational agents under superposition end up being wrong. In this post, I want to discuss a possible resolution to the paradox. Basically I'll be retreading the same ground as Scott Aaronson's post "It’s hard to think when someone Hadamards your brain", but with more details filled in.

When faced with a quantum paradox, I've found that a very good trick to try is to see if you can remove the quantum while keeping the paradox. For example, this trick works well on the delayed choice quantum eraser and also on quantum teleportation (though I guess that's not technically a paradox). There are of course cases where this de-quantizing strategy doesn't work, notably Bell inequality paradoxes (that's kind of the point of them, actually), but it's a good first thing to try.

Here's the sequence of events that are going to play out in this post. First, I'm going to describe the paradox from the paper. Second, I'm going to specify implementation details of some of the processes that are left unstated in the paper. In particular, I'll replace a complicated measurement with a single-qubit measurement conjugated by an uncomputation. Third, I'll argue that it's the uncomputation that's invalidating conclusions. Fourth, I'll give a classical situation exhibiting the same basic paradox. Let's get started.

The Frauchiger-Renner Paradox

Alice and Bob are quantum agents stored in quantum computers. Annette and Bennette are classical agents operating the quantum computers. Annette manages Alice's computer and Bennette manages Bob's computer.

Annette and Bennette are going to initialize a two-qubit entangled state, and spread it between the two computers. Specifically, they will prepare the state $|00\rangle + |01\rangle + |10\rangle$ and then give one of the qubits to Alice and the other to Bob.

Within the computers, Alice and Bob measure their qubits. Well, maybe measurement is the wrong word, since the quantum computers are not going to perform a literal measurement operation. Rather, the computers will execute unitary operations that correspond to measurement within their simulations of Alice and Bob. The computers will evolve Alice and Bob's state in a fashion that conditions on the qubits they've been handed.

Now let's imagine things from Bob's perspective. He picks up the qubit, and observes whether it is in the $|0\rangle$ state or the $|1\rangle$ state. Based on the value he observes, he can determine the implied state of Alice's qubit. If his qubit is in the $|0\rangle$ state, he knows that Alice's qubit must be in the $|+\rangle$ state (i.e. the $|0\rangle + |1\rangle$ state). If his qubit is in the $|1\rangle$ state, he knows that Alice's qubit must be in the $|0\rangle$ state. And of course this all holds true vice-versa for Alice observing her qubit and deducing about Bob's qubit.

Because the initial state has no $|11\rangle$ component, at least one of Alice and Bob must have seen $|0\rangle$ and concluded that the other is in the $|+\rangle$ state. Therefore a measurement that checks if either of them is in the $|+\rangle$ state must succeed with certainty. Since $|+\rangle$ has no overlap with $|-\rangle$, and at least one of the states is $|+\rangle$, the initial state must not overlap with the $|--\rangle$ state.

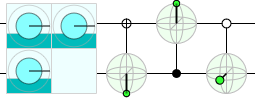

Here's another way to "prove" there's no overlap with $|--\rangle$, using a series of inferences that can be visualized using Quirk's conditioned displays:

From left to right, the conditioned displays read:

- If Alice's qubit is in the $|-\rangle$ state then Bob's qubit must be in the $|1\rangle$ state. (I.e. if you condition on an X basis control on one qubit then the bloch vector of the other qubit points down.)

- If Bob's qubit is in the $|1\rangle$ state then Alice's qubit must be in the $|0\rangle$ state. (I.e. if you condition on a Z basis control on one qubit then the bloch vector of the other qubit points up.)

- If Alice's qubit is in the $|0\rangle$ state then Bob's qubit must be in the $|+\rangle$ state. (I.e. if you condition on a Z basis anti-control on one qubit then the bloch vector of the other qubit points forward.)

If you naively follow the 1-2-3 inferrence chain, then you find that Alice's qubit being in the $|-\rangle$ state implies Bob's qubit being in the $|+\rangle$ state. Therefore there must be no overlap with the $|--\rangle$ state... right?

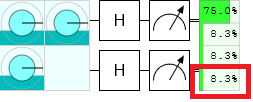

Anyways, the paradox is that the above reasoning is wrong. The initial state does have overlap with the $|--\rangle$ state, and so when Annette and Bennette perform an experiment where they measure the qubits in the X basis, to check the deductions made by Alice and Bob, about 8% of the time they will see an outcome that was concluded to be impossible:

As I've stated the paradox, it's not particularly compelling. The 1-2-3 inferrence chain that I set up was phrased a bit misleadingly, to hide the fact that the steps are only valid conditional on measuring in a particular basis. When you attempt to chain the more accurate statements, which are of the form "If Bob measures in the Z basis and Alice measures in the X basis and Bob got a $|1\rangle$ result then Alice got a $|+\rangle$ result", you find that it doesn't work because step 1 requires Alice to measure in the X basis while steps 2 and 3 require Alice to measure in the Z basis.

The main contribution of Frauchiger and Renner to this paradox is to fix the "not compelling" problem. Basically, they try to get around the "you have to assume the measurement basis to get the implication" problem by using a decision theory axiom to convert hypothetical reasoning by Alice into conclusions by Annette. In other words, they put the axioms of decision theory into conflict with the axioms of quantum theory, which implies big trouble if correct.

Implementation Details

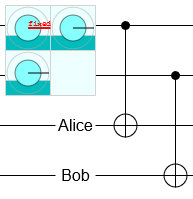

So far, I've been rather loose with the description of how Annette and Bennette go about performing their X basis measurements. In particular, I failed to mention that these measurements cannot be single-qubit measurements because the relevant qubits have been entangled with Alice and Bob. In the paper, Alice and Bob are modelled as individual qubits that the qubits of the input state are CNOT'd into, like this:

I prefer not to use single qubits to represent whole agents. An agent is a big complicated object with beliefs and inferences and hopes and dreams; to pack that all down into a single qubit is misleading to the intuition. So I will instead imagine agents as large multi-qubit systems, somewhat hazily specified. In order to write down what the measurement being performed actually is, I will define the following basis vectors:

$$|+_A\rangle = |\text{qubit=0},\text{Alice=thinking about qubit being 0}\rangle + |\text{qubit=1},\text{Alice=thinking about qubit being 1}\rangle$$

$$|+_B\rangle = |\text{qubit=0},\text{Bob=thinking about qubit being 0}\rangle + |\text{qubit=1},\text{Bob=thinking about qubit being 1}\rangle$$

$$|-_A\rangle = |\text{qubit=0},\text{Alice=thinking about qubit being 0}\rangle - |\text{qubit=1},\text{Alice=thinking about qubit being 1}\rangle$$

$$|-_B\rangle = |\text{qubit=0},\text{Bob=thinking about qubit being 0}\rangle - |\text{qubit=1},\text{Bob=thinking about qubit being 1}\rangle$$

When Alice concludes that Bob's qubit was in the $|+\rangle$ state, she is actually concluding that the Bob-and-his-qubit system is in the $|+_B\rangle$ state. And when Bennette measures "Bob's qubit in the X basis", he is actually performing a logical X basis measurement that distinguishes $|+_B\rangle$ from $|-_B\rangle$. Note that this measurement includes qubits defining the state of Bob's brain.

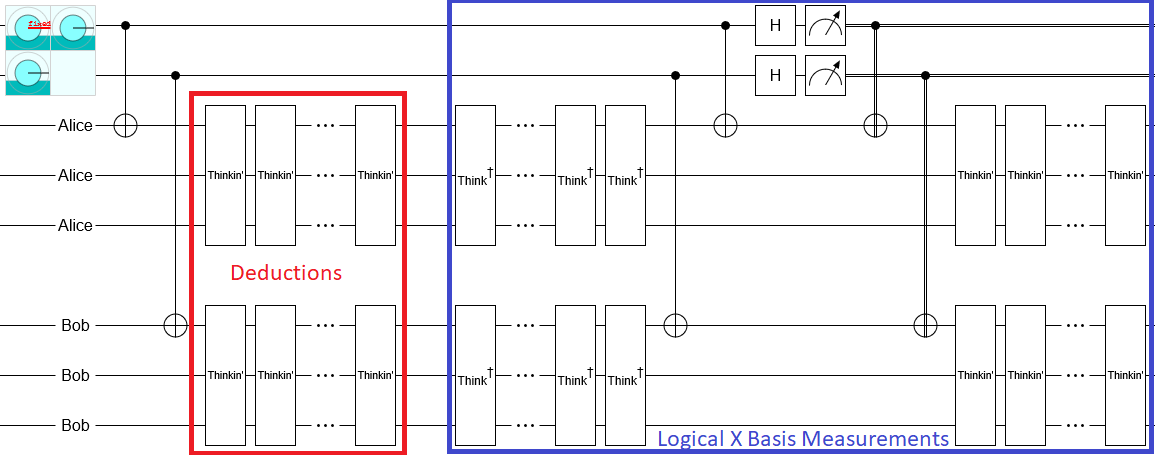

The paper does not specify a mechanism by which these logical X basis measurements are done, it just says that they are done. The lack of detail about implementation means that any mechanism should work, and I will pick one that makes my argument easy. To me, the simplest possible mechanism would be to get the state back onto a single qubit and perform the usual single-qubit X basis measurement. And the simplest way to get the state back onto a single qubit is to notice that it started that way, so whatever operations we did in between we just need to temporarily reverse. Therefore the experiment would be implemented like this:

where the "$\text{Thinkin'}$" gates are unitary operations corresponding to Alice and Bob's brains processing their observations, and making deductions. The "$\text{Think}^\dagger$" gates are the inverse unitary operation.

The key thing to notice about the above implementation is that all the deductions that Alice and Bob make are un-made during the measurement. Then, after the physical single qubit measurement, Alice and Bob accidentially repeat their deductions in the wrong context (note the Thinkin' gates on the right hand side). When Bob is thinking "Oh I saw $|0\rangle$ therefore Alice has $|+\rangle$", he is assuming that he is thinking this during the initial computation and not during the recomputation. (From Bob's perspective, these two scenarios are indistinguishable.) You can see how this would cause a problem; in order for Bob's conclusions to be completely correct he has to limit himself to things that would be true in both contexts.

I claim that this sloppiness with respect to context and recomputation is the core of the Frauchiger-Renner paradox.

Sleeping Beauty Problem

In the classical world, problems where agents attempt to reason under conditions where they are uncomputed/forced-to-forget are known as sleeping beauty problems. Here is my attempt to phrase the Frauchiger-Renner paradox as a sleeping beauty problem.

Annette tells Alice that Annette will wake Alice up once with an apple hidden under the bed, and then Annette will put Alice to sleep, erase Alice's memories, and wake Alice up again but with an orange under the bed. Each time Alice wakes, she must guess whether there is an apple or an orange under the bed. Alice decides to use the strategy that, whenever she wakes up, she says "this is the first time I woke up, therefore there is an apple under the bed". This strategy works during the first wake up, and then of course fails during the second wake up.

The phrasing I've used in the above paragraph makes the error in reason extremely obvious. But when you take this error and hide it behind formal postulates about what Annette can infer from Alice's reasoning as a rational agent, and when you obscure the fact that Alice is being woken up a second time, and when you phrase the whole thing in terms of a counter-intuitive physical theory, and when you don't prime the reader to look for this exact kind of mistake... well, then it's much harder to spot the problem. And that is what I believe the Frauchiger-Renner paradox is; a subtle way to dress up the mistake made in the previous paragraph.

Summary

Like Scott Aaronson said, it’s hard to think when someone Hadamards your brain. To be more specific, when someone performs a logical X basis measurement that includes the state of your brain, this measurement may be equivalent to forcing you to un-think and then re-think deductions that you made. This places an unexpected constraint on the deductions: they must be made with the understanding that they should be correct with respect to the initial state and also with respect to the state during the recomputation after the measurement.

This before-and-after constraint is what prevents the decision theoretic argument made in Frauchiger and Renner's paper from going through. The conclusions being made by Alice and Bob are valid the first time (with respect to the initial state) but not the second time (when they are being recomputed during the logical X basis measurements). Because Alice and Bob's reasoning is not sound, it is not sound for Annette and Bennette to use their conclusions. This dissolves the paradox.