Back in April, I read the pre-print "Lower bounds on the non-Clifford resources for quantum computations" by Beverland, Campbell, Howard, and Kliuchnikov. It defines an amazingly simple metric, the "stabilizer nullity" of a state, which is the number of qubits in the state minus the number of Pauli product stabilizers of the state. The authors of the pre-print then use this metric (and some others) to prove tight lower bounds on the number of magic states needed to produce/perform certain states/operations.

For example, the pre-print proves that you need to consume at least $N-2$ three-qubit CCZ states to produce one $N$ qubit CCZ state. By "$N$ qubit CCZ state" I mean the uniform superposition over all computational basis values of $N$ qubits, except the all-ones state has a negated phase. Algebraically, the state $\sum_{k=0}^{2^N-1} (-1)^{\left(k = 2^{N-1}\right)} |k\rangle$.

The pre-print also proves that at least $N-2$ three qubit CCZ states are needed to perform an $N$ qubit adder, and conjectures that this lower bound could be improved to $N-1$. Which brings us to the subject of this post because, as soon as I saw that conjecture, right next to the lower bound on the CCZ state, I had an idea for how to solve one using the other.

Every $N$-qubit adder secretly has an $N+1$ qubit CCZ operation hiding inside of it. An adder can be decomposed into a series of controlled increments: for eack $k$, increment the $N-k$ high bits of the target controlled by the $k$'th bit of the input. An $N$ qubit controlled increment can be decomposed into an uncontrolled $N+1$ qubit increment and a bit flip. An $N+1$ qubit increment can be decomposed into a triangle of C..CNOT gates, with the largest covering $N+1$ qubits. Conjugate the largest C..CNOT by Hadamards, and you have your $N+1$ qubit CCZ. So basically my idea was to try to find some way to avoid everything within the adder except for this one huge $N+1$ qubit $CCZ$ operation, and thereby produce an $N+1$ qubit CCZ state.

With my half-thought-out intuition in hand, I set to work. I opened up Quirk, plopped down an adder, made a guess at what separable input states the adder would entangle the most, noticed the guess was wrong but looked close, then tweaked for a few minutes. I know that's not a particularly, uh, "reproducible" description. I'm sure I could give a more reproducible-by-others explanation... but then that explanation wouldn't really be how I solved the problem. Sometimes quickly iterating on half-thought-out intuitions really is the right strategy.

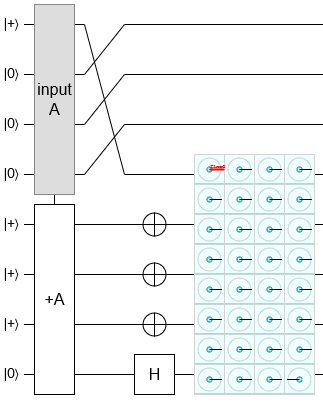

Anyways, here is the circuit I found:

Prepare the input register into the (little endian) state $|0\rangle^{\otimes N-1} |+\rangle$ and the target register into the (little endian) state $|+\rangle^{\otimes N-1} |0\rangle$. Apply the adder. Apply an X gate to every qubit of the target register, except for the most significant qubit where you apply a Hadamard gate instead. The result is an $N+1$ qubit CCZ state over the qubits of the target register and the least significant qubit of the input register.

Because we produced an $N+1$ qubit CCZ state using one $N$ qubit adder, and Beverland et al proved you need at least $N+1-2=N-1$ three qubit CCZ states to produce an $N+1$ qubit CCZ state, performing an $N$ qubit adder using three qubit CCZ states must consume at least $N-1$ three qubit CCZ states.

Closing Remarks

After figuring this out way back in April, I sent an email to the authors. There was no response, so I assumed they didn't think much of it. But then I met Michael Beverland at QEC2019 and he brought it up immediately. He even mentioned it in his presentation! Apparently the authors had discussed the trick and how to reply at length, but had ultimately forgotten to (oops) actually reply. They weren't quite sure how to incorporate the result into the paper. In fact, that's the main reason I'm making this blog post: so they have something they can cite.