An "erasure" is a quantum error where you accidentally lose a qubit (or reset a qubit), but realize that this happened. Erasures are common in quantum computers based on photons, for example. Although it sounds really bad to lose a qubit, the fact that you know when erasures happen actually makes erasures more benign than other kinds of errors. For example, the surface code can tolerate more erasure errors than it can tolerate (unknown) Pauli errors.

Recently I was trying to think of a simple algorithm to decide whether or not, given a set of erasures that occurred over time, the logical value of a surface code qubit had survived. There has been previous work on this problem, in particular "Linear-Time Maximum Likelihood Decoding of Surface Codes over the Quantum Erasure Channel" by Delfosse and Zémor. In that paper, erasures are corrected by finding a set of Pauli errors that would have symptoms equivalent to the observed detection events produced by the erasures. I wanted to approach the problem in a totally different way: instead of trying to fix the errors, just walk around them.

Moving observables around

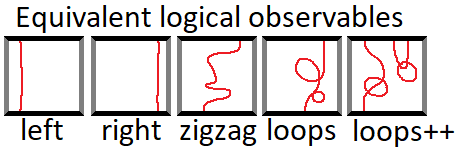

In the surface code, there is a lot of redundancy in how a logical qubit is encoded. For example, you can identify the top-to-bottom logical Z observable of a surface code patch as being on the left side of the patch, or on the right side of the patch, or zig zagging back and forth across the patch, or stopping halfway to do a loop, and all these different ways of thinking about the observable work fine. This flexibility gives you a lot of freedom, which becomes useful when errors are around. If an error has potentially corrupted the right side version of the logical Z observable, but not the left side version, then you can just use the left side version. If corrupting the right side could cause computations that only used the left side to fail, that would violate the no communication theorem.

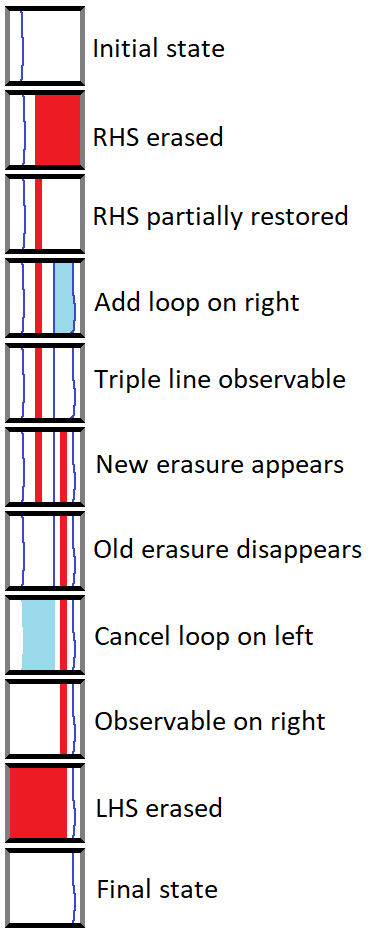

Here is a diagram showing various equivalent ways of identifying the same logical observable:

Each square represents a different way of thinking about the same surface code patch. Within each patch is a curve (or curves) indicating a set of physical Z observables that corresponds to the logical Z observable. Every one of the indicated sets is exactly equivalent, assuming all of the surface code's local stabilizers are in their +1 eigenstate.

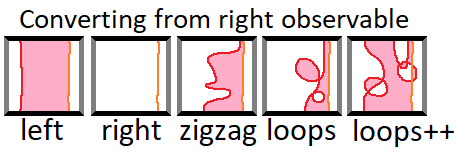

In the more general case, where some local stabilizers are in their -1 eigenstate, logical observables can be related by multiplying together the set of local stabilizers between them. Here are some diagrams that highlight in pink the stabilizers you have to multiply together to turn one observable (orange) into another (red):

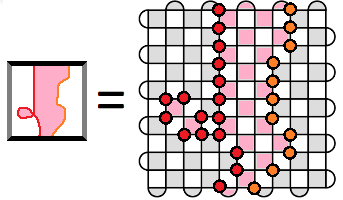

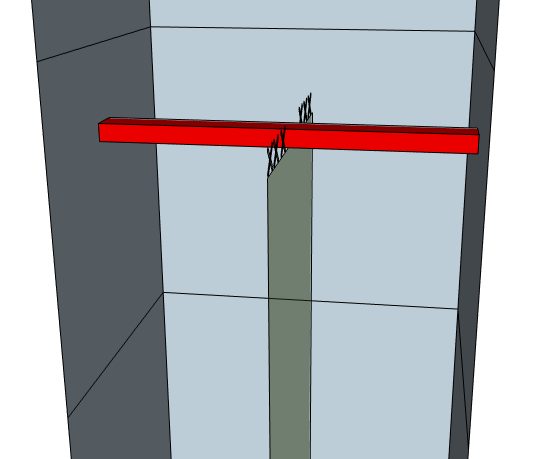

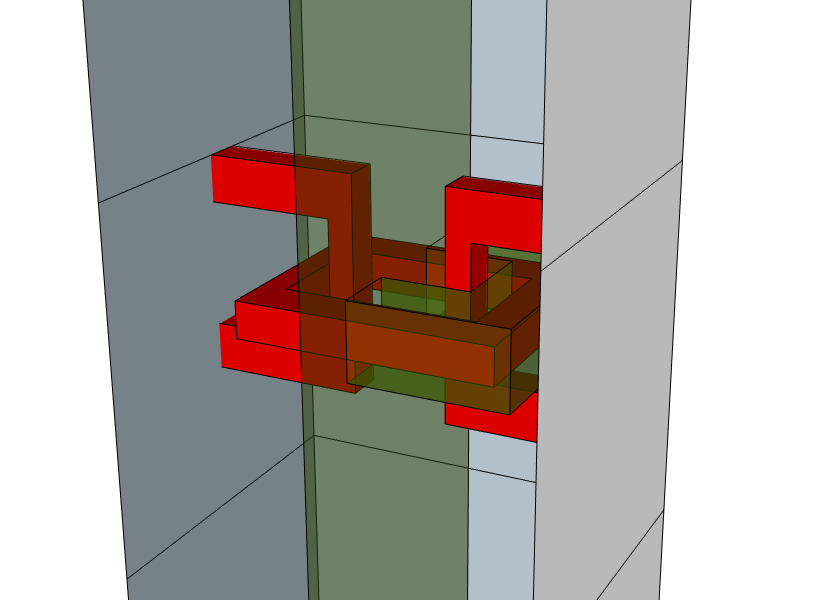

And here is a somewhat less abstract diagram making it clear exactly what is being multiplied:

The product of Z observables of data qubits covered in a red circle is equal to the product of Z observables of data qubits covered in an orage circle times the pink stabilizers (which are classically known because they are being measured).

Moving observables around erasures

When considering a computation, it is not enough to decide what the logical Z observable is at one point in time. We have to decide what it will be at each instant throughout the computation. Erasures will be coming and going, and we will need to move the observable around to dodge and weave around any erasures.

(Note that the location of the observable is purely a post-processing sort of thing. You don't need to decide where the observable is before being told where the erasures are. Choosing the observable's location over time is really just a way of choosing different strategies for decoding the logical qubit's value, given a record of stabilizer measurements and erasures that occurred.)

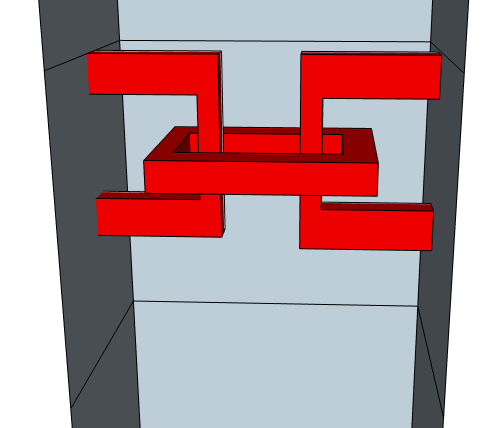

Here's an interesting example of an observable dodging erasures. In particular, the observable is dodging through time, not just through space:

In the above diagram, time goes from bottom to top and the surrounding frame represents the spatial boundaries of the surface code patch. The red blocks represent erasure errors occuring at particular times and places. The translucent green surface represents the logical qubit's Z observable over time. The vertical parts of the surface correspond to the observable staying the same, while horizontal parts correspond to multiplying together local stabilizers to move the observable. In this case the erasures form shelves with hooks, forcing us to move the logical Z observable up, and then back down (through time), in order to avoid getting erased.

Here is a step by step forward-in-time interpretation of what is happening in the above diagram:

If I had to pick the "surprising" step of the above diagram, it would be the step that adds the loop on the right to the observable. The stabilizers being multiplied together while adding that loop were completely randomized by the erasure. But it turns out, amazingly, that all that matters is that they are not changing as we cross through them. In a sense, we are using those stabilizer measurements to ensure entanglement is present, so that we can perform a quantum teleportation later. The fact that the entanglement was re-established after an erasure is inconsequential to the teleportation process.

Hopefully that single worked out step by step explanation of what the 3d notation represents was enough to familiarize you with the 3d notation. At least for me, the picture of a surface weaving through some obstacles is much more grokable than the step by step way of thinking about the process. The 3d notation is way easier to work with, even if it does appear to violate the arrow of time.

There are some erasure errors that observables cannot dodge. For example, if there is an erasure that crosses the entire patch, your logical qubit is dead no matter what:

(Note that you cannot terminate a Z observable chain on the left or right walls. Otherwise this would be solvable.)

Which brings us back to the question that seeded this whole post. Given a particular set of erasures, how do you determine if the logical qubit survived?

Chain link erasures

My original conception of the getting-the-observable-to-the-top problem was as what I guess I'll call a "string navigation problem". You have a stretchy string attached by magnets to opposite inside boundaries of a box. The box contains a mazelike assemblage of obstacles and walls and corridors. You are allowed slide the magnets along their respective sides of the box, but you can't pull them off of the side. Can you move the magnets and the attached string around inside the box such that the string ends up entirely at the top of the box? That's what I assumed the logical qubit survival problem was equivalent to.

I was coming up with ideas to solve this string navigation problem, and in tandem coming up with ideas for cases that might be hard, when I discovered a case that showed that the observable navigation problem is not at all like the string navigation problem. In particular, one of the potentially-hard cases I came up with was to have erasures that did not make a contiguous connection between the two boundaries, but were linked together in a way that was impossible to get a string through. That is to say, erasures that formed a chain link fence between the two boundaries, like this:

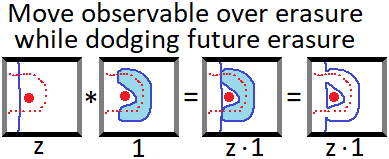

Obviously you are not going to be able to navigate the magnet-string-thing through this. But, very surpisingly, it turns out that you can navigate a logical Z observable through it! The key difference is the ability to perform the following transformation:

In the above diagram, the large red dot is an active erasure and the small dotted red line indicates an erasure that will be happening soon. The dark blue lines are products of physical Z observables. The goal is to get the Z observable shown on the left out of the way of the future erasure, despite the active erasure in the way. The diagram is showing that you can move an observable over the active erasure as long as you leave behind a disconnected observable loop around the erasure. Once the active erasure goes away you can contract the loop down into nothing, and in the mean time there's no overlap with the future erasure.

With a string you can't leave behind a disconnected loop. The string must always be one connected component. So it's not possible to loop around the active erasure without having part of the string in the way of the future erasure. This is a major difference between the two problems.

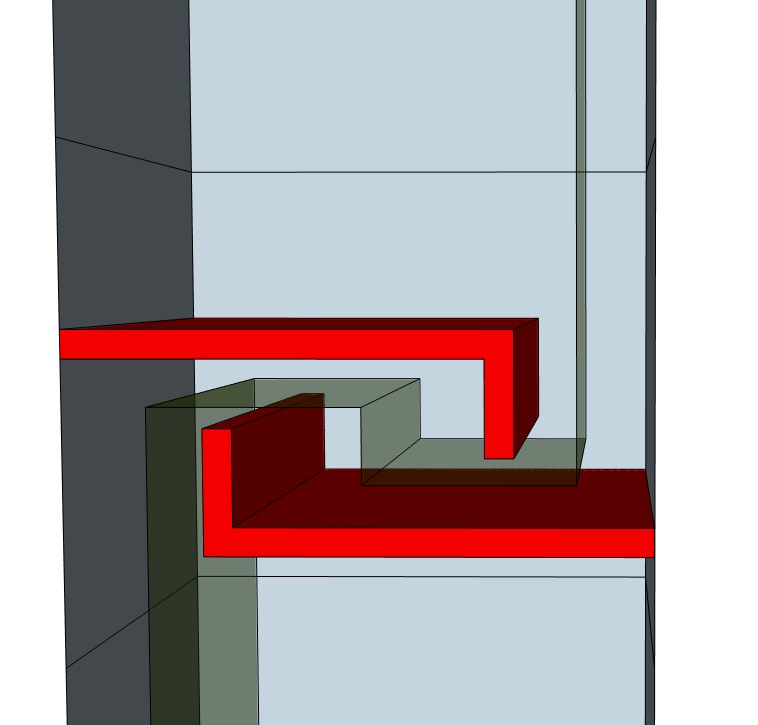

By using the disconnected loop move, we can get the logical Z observable through the chain link erasures. Here is a 3d diagram showing where the observable is at all times:

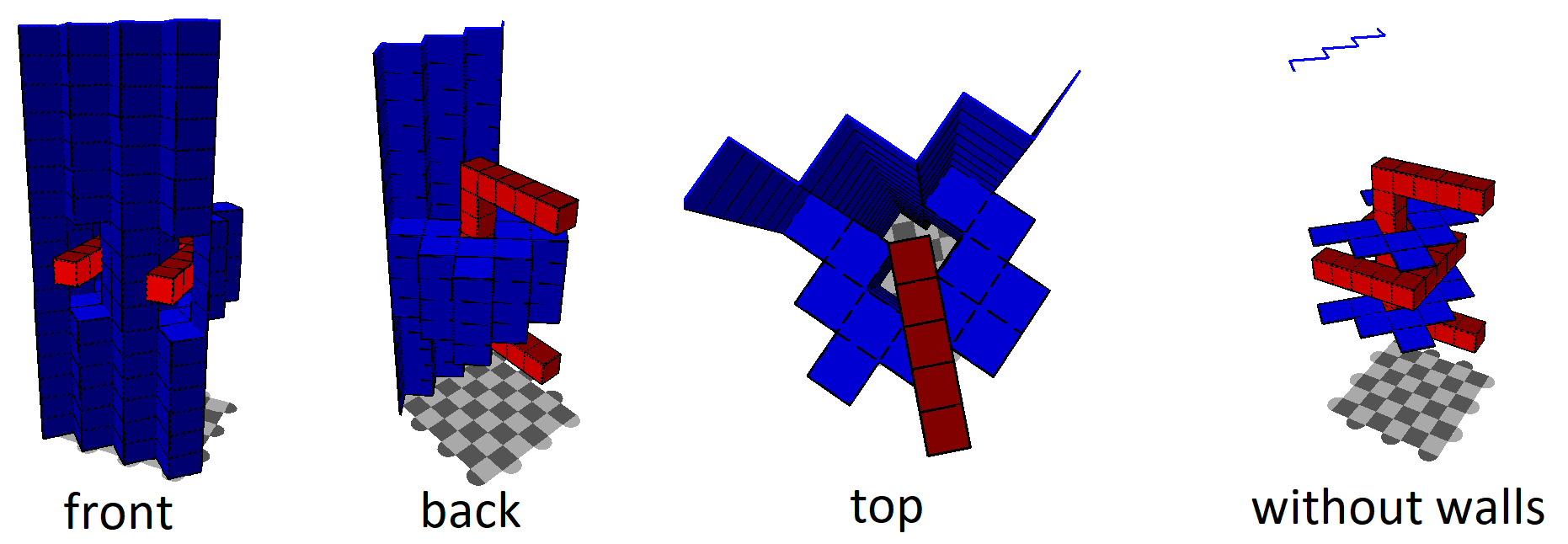

And here's some 3d models produced by code I wrote to simulate the situation and validate that, yes, this actually works:

The rightmost model is showing what stabilizers (blue squares) from what times to multiply onto the result, as well as the final data qubit measurements (blue line segments way up top) to multiply onto the result. The code produces that model, and also does several simulation runs to check that the erasures are not changing the measured logical value.

Summary

Topological observables are more flexible than topological strings. Observables can move over obstacles while leaving behind a disconnected loop. Strings can't do that. Observables can cross through a chain link fence (of erasures). Strings can't do that.

You can "error correct" erasures by simply using observables that don't touch the erasures. The only erasure that can destroy a logical qubit is a contiguous erasure connecting two logically disconnected boundaries.