In 2001, quantum computers factored the number 15. It’s now 2025, and quantum computers haven’t yet factored the number 21. It’s sometimes claimed this is proof there’s been no progress in quantum computers. But there’s actually a much more surprising reason 21 hasn’t been factored yet, which jumps out at you when contrasting the operations used to factor 15 and to factor 21.

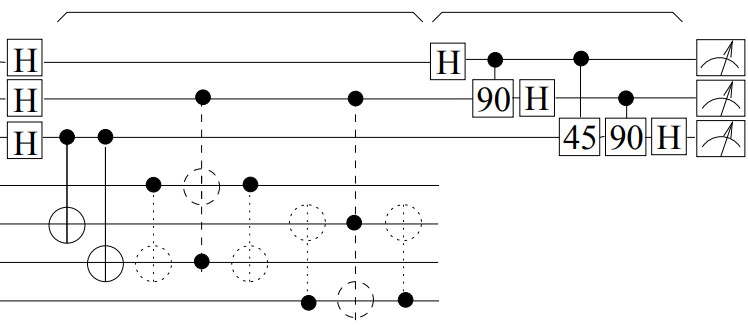

The circuit (the series of quantum logic gates) that was run to factor 15 can be seen in Figure 1b of “Experimental realization of Shor’s quantum factoring algorithm using nuclear magnetic resonance”:

The important cost here is the number of entangling gates. This factoring-15 circuit has 6 two-qubit entangling gates (a mix of CNOT and CPHASE gates). It also has 2 Toffoli gates, which each decompose into 6 two-qubit entangling gates. So there’s a total of 21 entangling gates in this circuit.

Now, for comparison, here is a circuit for factoring 21. Sorry for rotating it, but I couldn’t get it to fit otherwise. Try counting the Toffolis:

(Here’s an OPENQASM2 version of the circuit, so you can test it produces the right distribution if you’re inclined to do so.)

In case you lost count: this circuit has 191 cnot gates and 369 Toffoli gates, implying a total of 2405 entangling gates. That’s 115x more entangling gates than the factoring-15 circuit. The factoring-21 circuit is more than one hundred times more expensive than the factoring-15 circuit.

When I ask people to guess how many times larger the factoring-21 circuit is, compared to the factoring-15 circuit, there’s a tendency for them to assume it’s 25% larger. Or maybe twice as large. The fact that it’s two orders of magnitude more expensive is shocking. So I’ll try to explain why it happens.

(Quick aside: the amount of optimization that has gone into this factoring-21 circuit is probably unrepresentative of what would be possible when factoring big numbers. I think a more plausible amount of optimization would produce a circuit with 500x the cost of the factoring-15 circuit… but a 100x overhead is sufficient to make my point. Regardless, special thanks to Noah Shutty and Sid Madhuk for making tools and running expensive computer searches to find the conditional-multiplication-by-4-mod-21 subroutine used by this circuit. Also, I apologize for not doing any inter-multiplication optimizations, resulting in small amounts of waste at the boundaries between multiplications.)

Where does the 100x come from?

A key background fact you need to understand is that the dominant cost of a quantum factoring circuit comes from doing a series of conditional modular multiplications under superposition. To factor an $n$-bit number $N$, Shor’s algorithm will conditionally multiply an accumulator by $m_k = g^{2^k} \pmod{N}$ for each $k < 2n$ (where $g$ is a randomly chosen value coprime to $N$). Sometimes people also worry about the frequency basis measurement at the end of the algorithm, which is crucial to the algorithm’s function, but from a cost perspective it’s irrelevant. (It’s negligible due by an optimization called “qubit recycling”, which I also could have used to reduce the qubit count of the factoring-21 circuit, but in this post I’m just counting gates so meh).

There are three effects that conspire to make the factoring-15 multiplications substantially cheaper than the factoring-21 multiplications:

- All but two of the factoring-15 multiplications end up multiplying by 1.

- The first multiplication is always ~free, because its input is known to be 1.

- The one remaining factoring-15 multiplication can be implemented with only two CSWAPs.

Let’s consider the case where $g=2$. In that case, when factoring 15, the constants to conditionally multiply by would be:

>>> print([pow(2, 2**k, 15) for k in range(8)])

[2, 4, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

First, notice that the last six constants are 1. Multiplications by 1 can be implemented by doing nothing. So the factoring-15 circuit is only paying for 2 of the expected 8 multiplications.

Second, notice that the first conditional multiplication (by 2) will either leave the accumulator storing 1 (when its control is off) or storing 2 (when its control is on). This can be achieved much more cheaply by performing a controlled xor of $1 \oplus 2 = 3$ into the accumulator.

Third, notice that the only remaining multiplication is a multiplication by 4. Because 15 is one less than a power of 2, multiplying by 2 modulo 15 can be implemented using a circular shift. A multiplication by 4 is just two multiplications by 2, so it can also be implemented by a circular shift. This is a very rare property for a modular multiplication to have, and here it reduces what should be an expensive operation into a pair of conditional swaps. (If you go back and look at the factoring-15 circuit at the top of the post, the 2 three-qubit gates are being used to implement these two conditional swaps.)

You may worry that these savings are specific to the choice of $g=2$ and $N=15$. And they are in fact specific to $N=15$. But they aren’t specific to $g=2$. They occur for all possible choices of $g$ when factoring 15.

For contrast, let’s now consider what happens when factoring 21. Using $g=2$, the multiplication constants would be:

>>> print([pow(2, 2**k, 21) for k in range(10)])

[2, 4, 16, 4, 16, 4, 16, 4, 16, 4]

This is going to be a lot more expensive.

First, there’s no multiplications by 1, so the circuit has to pay for every multiplication instead of only a quarter. That’s a ~4x relative cost blowup vs factoring 15. Second, although the first-one’s-free trick does still apply, proportionally speaking it’s not as good. It cheapens 10% of the multiplications rather than 50%. That’s an extra ~1.8x cost blowup vs factoring 15. Third, the multiplication by 4 and 16 can’t be implemented with two CSWAPs. The best conditionally-multiply-by-4-mod-21 circuit that I know is the one being used in the diagram above, and it uses 41 Toffolis. These more expensive multiplications add a final bonus ~20x cost blowup vs factoring 15.

(Aside: multiplication by 16 mod 21 is the inverse of multiplying by 4 mod 21, and the circuits are reversible, so multiplying by 16 uses the same number of Toffolis as multiplying by 4.)

These three factors (multiplying-by-one, first-one’s-free, and multiplying-by-swapping) explain the 100x blowup in cost of factoring 21, compared to factoring 15. And this 100x increase in cost explains why no one has factored 21 with a quantum computer yet.

Closing remarks

Another contributor to the huge time gap between factoring 15 and factoring 21 is that the 2001 factoring of 15 was done with an NMR quantum computer. These computers were known to have inherent scaling issues, and in fact it’s debated whether NMR computers were even properly “quantum”. If the 2001 NMR experiment doesn’t count, I think the actually-did-the-multiplications runner-up is a 2015 experiment done with an ion trap quantum computer (discussed by Scott Aaronson at the time).

Yet another contributor is the overhead of quantum error correction. Performing 100x more gates requires 100x lower error, and the most plausible way of achieving that is error correction. Error correction requires redundancy, and could easily add a 100x overhead on qubit count. Accounting for this, I could argue that factoring 21 will be ten thousand times more expensive than factoring 15, rather than “merely” a hundred times more expensive.

There are papers that claim to have factored 21 with a quantum computer. For example, here’s one from 2021. But, as far as I know, all such experiments are guilty of using optimizations that imply the code generating the circuit had access to information equivalent to knowing the factors (as explained in “Pretending to factor large numbers on a quantum computer” by Smolin et al). Basically: they don’t do the multiplications, because the multiplications are hard, but the multiplications are what make it factoring instead of simpler forms of period finding. So I don’t count them.

There is unfortunately a trickle of bullshit results that claim to be quantum factoring demonstrations. For example, I have a joke paper in this year’s sigbovik proceedings that cheats in a particularly silly way. More seriously, I enjoyed “Replication of Quantum Factorisation Records with an 8-bit Home Computer, an Abacus, and a Dog” making fun of some recent egregious papers. I also recommend Scott Aaronson’s post “Quantum computing motte-and-baileys”, which complains about papers that benchmark “variational” factoring techniques while ignoring the lack of any reason to expect them to scale.

Because of the large cost of quantum factoring numbers (that aren’t 15), factoring isn’t yet a good benchmark for tracking the progress of quantum computers. If you want to stay abreast of progress in quantum computing, you should be paying attention to the arrival quantum error correction (such as surface codes getting more reliable as their size is increased) and to architectures solving core scaling challenges (such as lost neutral atoms being continuously replaced).