In 2021, Renou et al published the paper “Quantum theory based on real numbers can be experimentally falsified” in Nature. It caused a decent sized splash at the time. A quick search revealed articles in Quanta and Scientific American and APS News, as well as a talk at QIP 2022.

In this post, I’m going to explain why the title of the paper is wrong.

The Goal

Before we get going, I need to warn you away from a common misunderstanding of Renou et al’s claim.

Renou et al are NOT claiming that it’s impossible to write down math that behaves like quantum mechanics without using the word “complex” or the symbol “$\mathbb{C}$”.

That would be vacuously wrong, because you can just mimic the behavior of complex numbers using pairs of real numbers (and appropriately tweaked definitions of operations).

No one is claiming it’s impossible to write the C code struct complex { float real; float imag; };.

What Renou et al are actually claiming is that if you start with quantum mechanics, and then remove all operations and states involving non-real numbers, and then try to emulate what was lost using what remains, you will fail in an experimentally detectable way.

The way I like to think about this is in terms of quantum gatesets. The following gateset is known to be universal: the Toffoli gate (“CCX”), the Hadamard gate (“H”), the Measurement gate (“M”), and the 45° phasing gate (“T”). Roughly speaking: the Toffoli provides classical computation, the Hadamard provides superposition, the measurement provides results, and the T gate provides the complex plane. Only the T gate needs complex numbers to describe; the other three can be described using real numbers. What Renou et al are trying to do is make a test that this CHMT gateset (CCX + H + M + T) can pass, but the T-missing CHM gateset (CCX + H + M) can’t pass.

Imagine you’re buying a quantum computer from Eve. Eve claims the computer supports the CHMT gateset. You’re suspicious. You suspect it can’t actually do T gates, meaning it actually only supports the CHM gateset. Without T gates, you’d be stuck in the “real-only” subset of quantum computations. Is there some test you can do, some challenge you can give to Eve, that she can only pass if the T gate is working? Some kind of externally verifiable proof that the computer isn’t stuck in the real-only subset?

(A trivial solution would be to bring a trusted quantum computer and ask Eve to produce 100 copies of the state $|0\rangle + i|1\rangle$ and transmit them to the trusted computer. The trusted computer then simply verifies they all produce +1 when measured in the Y basis. But this solution doesn’t translate back to the physics use case that Renou et al have in mind, where basically the whole universe isn’t trusted, so I’m not going to allow it. Assume the verifier only has a classical computer.)

At first, you might think it’s easy to tell if the T gate is broken. Just ask Eve to do a quantum computation involving complex numbers. For example, Shor’s algorithm ends with a Quantum Fourier Transform which is defined in terms of complex values. Just ask Eve to factor some numbers. Alas, this doesn’t work. Although the gateset CHM isn’t strictly universal, it’s still computationally universal. Any CHMT circuit can be efficiently compiled into, and emulated by, the CHM gateset.

Hearing that, you may now think it’s obviously impossible to determine if Eve’s computer can’t do T gates. However, there’s still hope: the compilation into CHM may not be locality preserving. Operations that used to be local may now need to interact. This is how “Bell tests” distinguish the classical gateset CMT from the universal gateset CHMT. Classical computers can simulate quantum computers with exponential overhead, so a fast enough classical computer can technically pass any computational test you give. But, crucially, the classical simulation of quantum circuits isn’t locality-preserving. And there’s provably no way to fix that. So all you need to do is ask Eve to distribute the computation over multiple computers, with crucial steps done under spacelike-separation. There are tests, such as the CHSH test, that CHMT computers can pass when spacelike-separated but that CMT computers cannot pass when spacelike-separated.

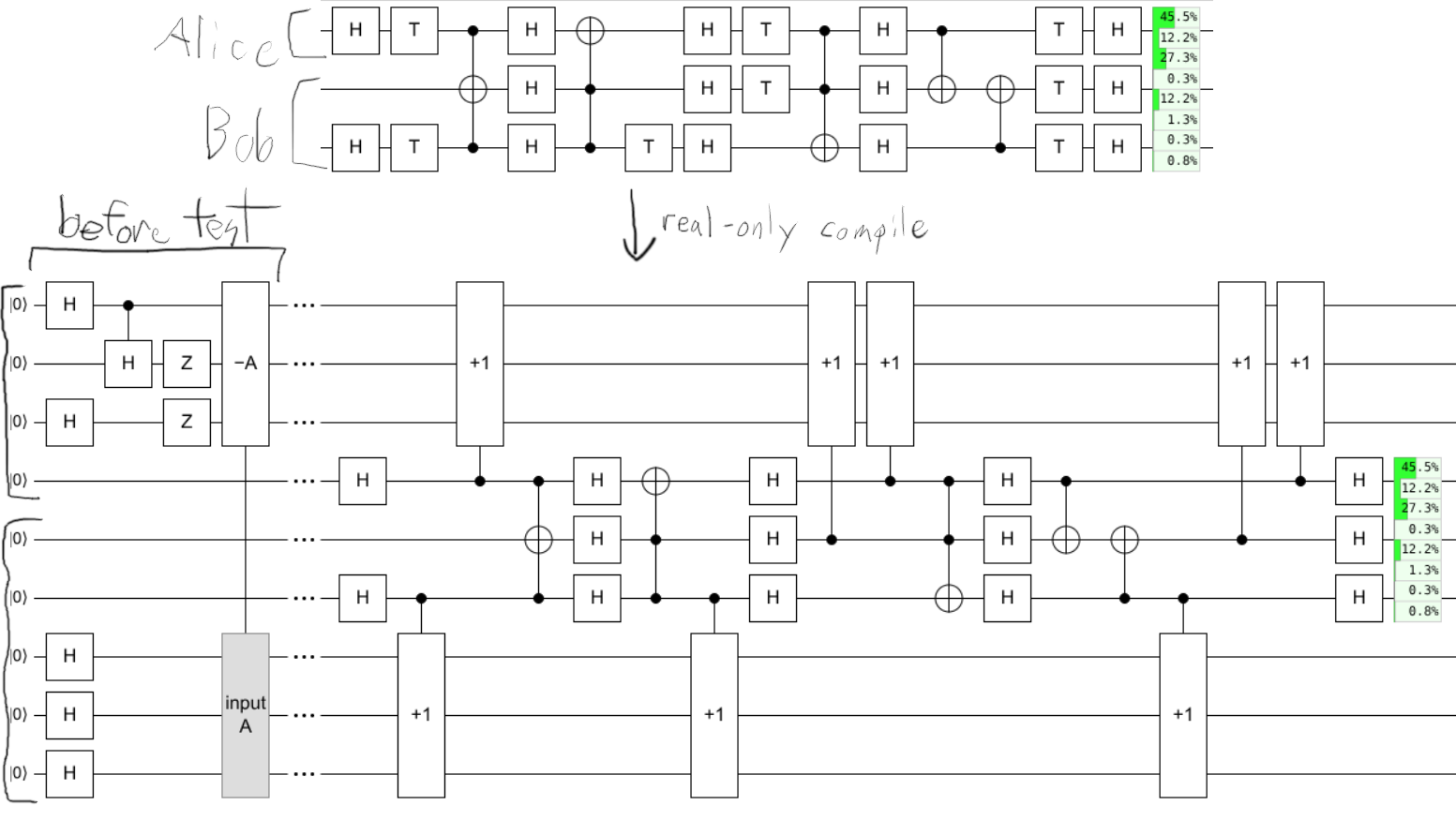

What Renou et al attempt to do is come up with an analogue of the CHSH test: use locality to distinguish CHM vs CHMT. At this point in the post, it would perhaps be appropriate to describe the details of Renou et al’s test. Roughly speaking, they define a computation distributed over three quantum computers (Alice and Bob and Charlie) where Alice and Charlie are doing a generalized version of the CHSH inequality mediated by entanglement swapped through Bob. However, ultimately these details don’t matter. There are locality-preserving ways to compile CHMT circuits into CHM circuits, making the whole idea moot.

The Spoof

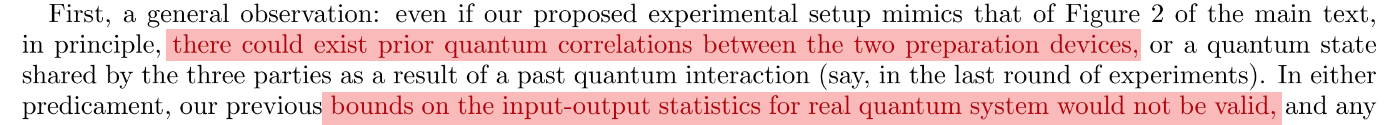

It’s well known that phasing operations, like the T gate, can be achieved using phase kickback. In particular, the T gate can be achieved with kickback from conditionally incrementing into a “phase gradient” state $|G\rangle = (|0\rangle - |1\rangle) \otimes (|0\rangle - i|1\rangle) \otimes (|0\rangle + \sqrt{-i}|1\rangle)$. Here is that fact as a circuit identity:

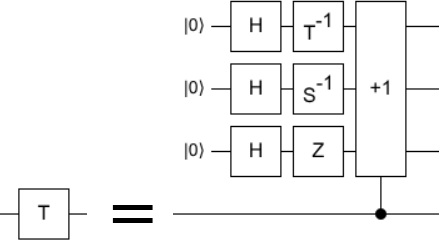

This may seem like a silly rewrite to do, because the phase gradient preparation also has a T gate. We’re replacing a T gate with a T gate plus more. However, phase gradients are reusable. With access to classical reversible arithmetic (i.e. the Toffoli gate), one phase gradient can catalyze arbitrarily many T gates:

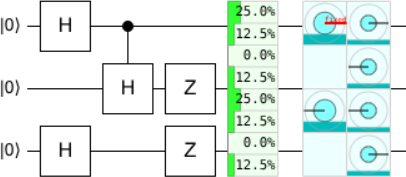

Of course, we don’t want all T gates to be replaced with increments targeting one single phase gradient. That would require communicating the gradient back and forth, which would break in spacelike-separated contexts. Fortunately, the CHM gateset can also duplicate phase gradients. Initializing the state $|+\rangle \otimes |+\rangle \otimes |+\rangle$, and then subtracting out of an existing phase gradient, duplicates the phase gradient:

Before the test begins, Eve can create one phase gradient state and then use this duplication procedure to expand it into one copy for each computer. The copies must be distributed before the test begins so that during the test no locality-violating steps are needed. This reduces the number of T gates in the circuit from arbitrarily-many to $O(1)$. So we’ve made substantial progress, but still have a bit further to go. Because the phase gradient state isn’t a real-only state.

Let $C$ refer to the circuit where T gates have been replaced by conditional increments, all ultimately leading back to a single phase gradient preparation at the beginning of the circuit. The only complex values that appear anywhere in $C$ are in the initial phase gradient preparation. Interestingly, this means $C$ will still function correctly if we replace the phase gradient with its conjugate. It’s well known that if you take any piece of math and globally replace the complex unit $i$ with its negation $(-i)$, all the equations remain true. For example, consider the equation $i^2 = -1$. Substituting $i \rightarrow (-i)$ produces $(-i)^2 = -1$, which is still true. The technical name for this fact is “the non-trivial field automorphism of the complex numbers”. That’s a bit of a mouthful, so I’ll just call it “conjugation symmetry”. Because of conjugation symmetry, statements like “$C$ passes the test” must remain true when we globally substitute $i \rightarrow (-i)$. For $C$ this just means replacing the phase gradient $|G\rangle$ with its conjugate $|G^\ast\rangle = (|0\rangle - |1\rangle) \otimes (|0\rangle + i|1\rangle) \otimes (|0\rangle + \sqrt{i}|1\rangle)$. Said another way: it doesn’t matter if we use the “clockwise winding” phase gradient or the “counter-clockwise winding” phase gradient. It’s the consistency of the winding that matters, not the direction.

Not only do the clockwise and counter-clockwise winding phase gradients work equally well, but any superposition $|G^\prime\rangle = \alpha |G\rangle + \beta |G^\ast\rangle$ of the two will work equally well. Let $C^\prime$ be a variant of $C$ that is preparing the superposition $|G^\prime\rangle$, instead of $|G\rangle$. Note that, after $|G^\prime\rangle$ is prepared, every operation in $C^\prime$ that acts on the qubits storing $|G^\prime\rangle$ are either subtracting out of or conditionally incrementing into those qubits. These operations have a common eigenspace over the qubits of $|G^\prime\rangle$: the frequency basis. Let $C^{\prime\prime}$ be $C^\prime$ with an additional discarded frequency basis measurement of the qubits storing $|G^\prime\rangle$, at the end of the circuit. By the no-communication theorem, $C^{\prime\prime}$ and $C^\prime$ are observationally indistinguishable. Let $C^{\prime\prime\prime}$ be $C^{\prime\prime}$, but with the discarded frequency basis measurement moved from the end of the circuit all the way back to immediately after $|G^\prime\rangle$ is prepared. By the deferred measurement theorem, $C^{\prime\prime\prime}$ and $C^{\prime\prime}$ are observationally indistinguishable. In $C^{\prime\prime\prime}$, the frequency basis measurement immediately collapses $|G^\prime\rangle$ into either $|G\rangle$ or $|G^\ast\rangle$. The collapse either results in $C^{\prime\prime\prime}$ having the same gradient state as $C$ (which works) or its conjugate (which also works, due to conjugation symmetry). Therefore $C^{\prime\prime\prime}$ works, therefore $C^{\prime\prime}$ works, therefore $C^\prime$ works, therefore we can use any $|G^\prime\rangle = \alpha |G\rangle + \beta |G^\ast\rangle$ instead of $|G\rangle$.

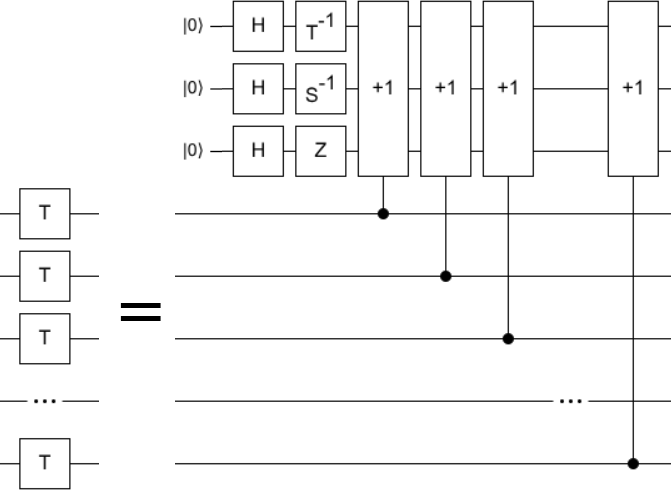

With this newfound freedom, I chose $|G^\prime\rangle$ to be a uniform superposition of the two windings. This causes their imaginary parts to cancel, leaving behind real amplitudes proportional to a cosine (because $e^{i\theta} + e^{-i \theta} \propto \cos \theta$):

\[\begin{aligned} |G^\prime\rangle &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} |G\rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} |G^\ast\rangle \\&= \frac{1}{2} |0\rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt{8}}|1\rangle - \frac{1}{\sqrt{8}}|3\rangle - \frac{1}{2}|4\rangle - \frac{1}{\sqrt{8}}|5\rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt{8}}|7\rangle \\&= \begin{bmatrix} \sqrt{2} \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ -1 \\ -\sqrt{2} \\ -1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} / \sqrt{8} \end{aligned}\]This state is real-only, and can be prepared using real-only gates:

Note that the above circuit uses gates like controlled-H and Z. The CHM gateset can approximate these gates to any desired precision, but it’s tedious to do. For the purposes of this post, it’s not worth going through the exercise. (Similarly, all the increments and subtractions and such in the other examples can be tediously compiled into CHM.)

One note of caution: with the original phase gradient state $|G\rangle$, there was no distinction between using the duplication-by-subtraction circuit and simply independently preparing another instance of $|G\rangle$. Both processes perform $|G\rangle \rightarrow |G\rangle \otimes |G\rangle$. This isn’t true for $|G^\prime\rangle$. The duplication-by-subtraction circuit doesn’t perform $|G^\prime\rangle \rightarrow |G^\prime\rangle \otimes |G^\prime\rangle$. It creates an “entangled copy” instead of an independent copy. Replacing these entangled copies with independent copies of $|G^\prime\rangle$ would break the construction, so don’t do that.

Summarizing, Eve can pretend to perform any complex-allowed distributed quantum computation using real-only quantum computers as follows. Before testing begins (perhaps even before the test is known) distribute entangled copies of $|G^\prime\rangle$ to each computer (by preparing one instance then using the duplication-by-subtraction circuit to get entangled copies). Once the testing circuits are specified, perform inplace compilation of the testing circuits into the CHMT gateset using standard techniques. Once the test begins, run the CHMT circuits except replace every instance of T with a controlled increment into the local entangled copy of $|G^\prime\rangle$. This is provably observationally indistinguishable from running the original complex-allowed circuit.

As an example, I manually applied this compilation to an arbitrary circuit I threw together. The green chance displays show that the original circuit and the compiled circuit output identical probability distributions:

This spoofing procedure will work for any protocol, and so it will also happen to work on the one presented in “Quantum theory based on real numbers can be experimentally falsified”.

Where’s the mistake?

Renou et al’s paper includes a proof that real-only quantum mechanics can’t spoof their test. I just constructively proved that real-only quantum mechanics can spoof the test. These proofs contradict each other, so one of them must have a mistake. Where’s the mistake?

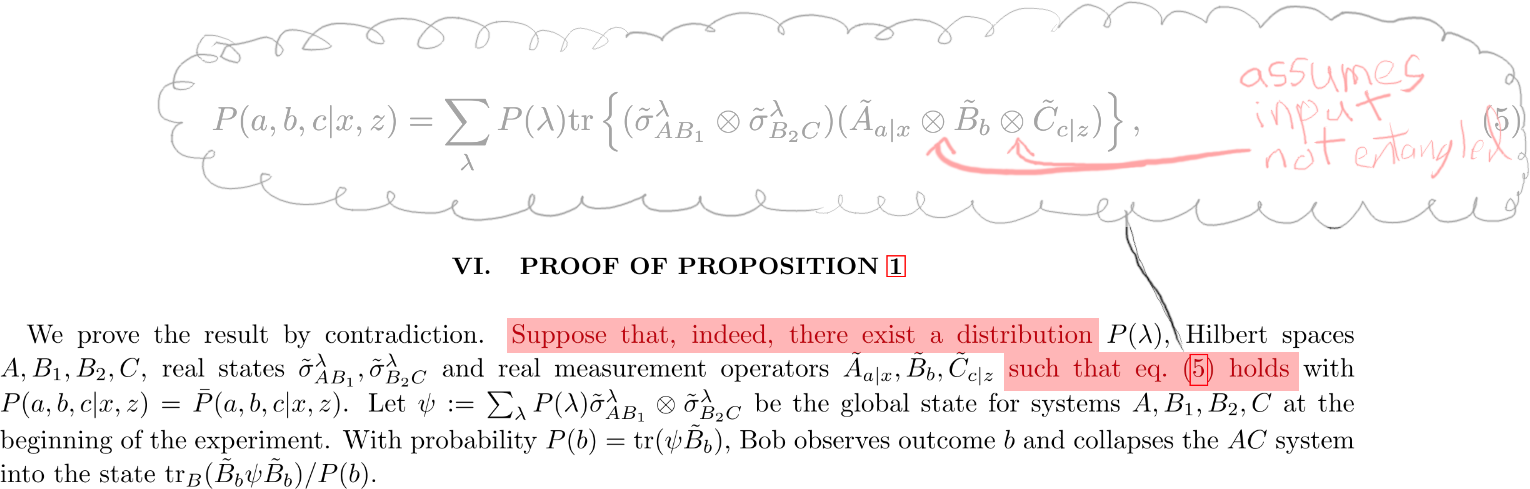

The mistake occurs in the first sentence of section VI of the supplementary material to Renou et al’s paper. The spoofing construction I described in this post distributes entangled states to the real-only players before the test begins. Renou et al assume the real-only players start without any such entangled states:

(highlights and squiggly annotations are from me)

However… it’s not quite right to call this a mistake.

Digging further into the supplement, on page 14 out of 15, I found this:

…they knew.

They KNEW.

They knew entanglement broke the test!

Entanglement is not rare in quantum mechanics. Especially in the context of tests involving locality, the presence of entanglement is a common feature. For example, pre-sharing entanglement is the basis for all Bell inequality violations, which is the foundation that Renou et al’s paper is built upon. Not allowing the players to come into the game with entangled states is really, really strange. I had no idea they were making this assumption, and neither did anyone I asked. I only found out after I’d finished finding construction described in this post, while doing my due diligence to exactly characterize the nature of the mistake.

(Update: @fariddiequantum pointed out that the word “independent”, for example as in “network scenarios comprising independent states and measurements” from the abstract, is communicating that the states aren’t entangled. I completely failed to parse that meaning when reading the paper, but in hindsight it makes sense. I’ll leave the end of the post unedited, but keep that in mind.)

They could have put this caveat in the paper’s abstract. They could have put it in the introduction, or in the conclusion, or somewhere in the body. Maybe in a figure caption. Instead, they hid it away on page 14 of the supplementary materials. Frankly, if this had been my paper, I’d have put this caveat in the TITLE. “Quantum theory based on real numbers can be experimentally falsified, unless entanglement is present, which it easily could be, and we have no way of testing that it isn’t”; it flows right off the tongue.

Look, I’ll admit that doing a test fooled by entanglement is better than doing no test at all. Early Bell tests, done without spacelike-separation, were analogously better than nothing. But if you’re going to rest the correctness of your experiment on asking Eve to pinky promise not to cheat despite her means, motive, and opportunity… I would appreciate a clearer warning.