One of the things I have a hard time intuiting, in quantum computing, is the interplay between classical bits and quantum bits. A good example of this is superdense coding. Superdense coding encodes two classical bits into a single transmitted qubit, by taking advantage of a previously shared qubit.

(Superdense coding is also fun to say.)

Thought of another way, superdense coding turns previously entangled qubits into a fuel you can store and then later consume to double your bandwidth. Which is what I mean when I say superdense coding lets you store bandwidth.

Superdense Coding

In case you don't want to watch this video explaining superdense coding (I'd recommend the whole series it's part of), I will explain it here.

In order to do superdense coding you need three things:

- A way to store qubits.

- A quantum communication channel to transmit qubits.

- The ability to do a few quantum operations to qubits.

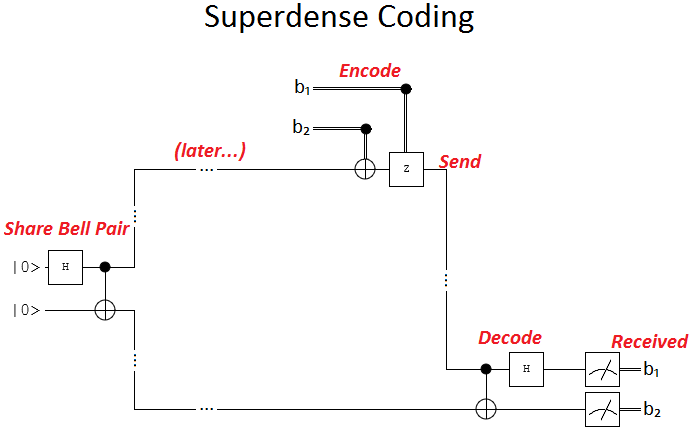

The actual protocol is not too complicated, although understanding why it works can be. Here is a quantum circuit diagram showing what happens, which I will explain below:

Imagine that Alice is the one who wants to send information, and Bob is the one who will receive it. Alice roughly corresponds to the top of the diagram, and Bob to the bottom. The sequence of events, from left to right, is as follows.

First, ahead of time, Alice and Bob each get half of a Bell pair. That is to say, two qubits are placed into a superposition where either both are false or both are true, and then Alice and Bob each take one of those qubits.

There's a lot of flexibility in who actually makes the Bell pair. Alice can do it, Bob can do it, or an unrelated third party can do it. Regardless, what matters is that the Bell pair can be delivered ahead of time and stored for later use.

Second, Alice decides what information she wants to send to Bob. She can send two bits (i.e. one of four possibilities). We'll call the possible messages 00, 01, 10, and 11.

Third, Alice encodes the message by applying operations to her qubit (the one from the Bell pair). The operations are based on the message she wants to send. If she wants to send 00, she does nothing. For 01, she rotates the qubit 180° around its Z axis. For 10 she instead rotates 180° around its X axis. Otherwise the message is 11 and she rotates both 180° around the X axis and then 180° around the Z axis.

Note that the 11 case is technically a rotation around the Y axis, but it's nice to split it into X and Z rotations because it makes the circuit simpler. It means Alice can just apply the X rotation if the second bit is true, and afterwards the Z rotation if the first bit is true.

Fourth, Alice sends her qubit to Bob. So Bob will end up with both halves of the Bell pair, but Alice has operated on one of them.

Fifth, Bob does a decoding operation. He conditionally-nots his qubit, conditioned on Alice's qubit. This will flip the value of his qubit in the parts of the superposition where hers is true. Then he rotates Alice's qubit by 180° around the diagonal X+Z axis (i.e. applies the Hadamard operation).

Note that the decoding operation Bob applies is actually the inverse of how the Bell pair is made. Normally the decoding operation would just "unmake" the pair, leaving Bob with two qubits set to false and not in superposition. That's why Alice applying no operation corresponds to sending 00. The reasons the other operations give the right results are a bit harder to explain, and I won't try here, but the qubits do always end up in the right state.

Finally, Bob measures the two qubits and retrieves the message.

Storing Bandwidth

The interesting thing about superdense coding is that, although Bob still has to receive one qubit per classical bit, one of the qubits can be sent far in advance. Then, when the actual message has to be sent, half of what's needed to reconstruct it has already arrived.

So, basically, the pre-shared Bell pairs let you store bandwidth. They are a fuel that you consume to transmit at double speed.

This would do interesting things to network design.

For example, during times of low utilization you could use the remaining capacity to share Bell pairs and build up bandwidth to be consumed during high utilization. This would smooth out traffic peaks.

Alternatively, you could double the bandwidth of a low-latency channel by continuously making Bell pairs on a secondary high latency channel. (Imagine a truck showing up every day to drop off a box filled with trillions of qubits in Bell pairs, so your internet can go faster.)

Of course all of this assumes that you'll want to use quantum channels to send classical information. Maybe classical channels will simply be more than twice as fast (do photons decohere when sent over fiber?). Maybe quantum channels will be too expensive to bother. Maybe we'll be too busy sending qubits over them to spare time to send classical bits.

There's tons of practical reasons it might not work out. But still, I enjoy the hypothetical image of trucks dropping off boxes of internet-go-fast.

Summary

Superdense coding exploits empowers a quantum communication channel to send, ahead of time, half of what will be needed to reconstruct a classical message. This lets you transmit at double speed until the pre-delivered qubits run out.