Symmetry Breaking

One of the many primitives used by distributed algorithms is symmetry breaking. A symmetry breaking primitive takes two identical nodes, does its thing, and ends up assigning true to one node and false to the other (and the nodes agree about who got which value).

Symmetry breaking algorithms typically rely on some form of randomness. For example, you may have a sequence of rounds where each node flips a coin then broadcasts the result. Whenever the coin flips agree, that's a failure and the nodes try again. Once the coins finally differ, the node that flipped tails gets true and the other gets false. To avoid incurring many round trip delays due to failures, you can batch hundreds of flips into each message.

The fact that symmetry breaking algorithms have "if it fails then retry" steps is not an issue in practice, but it does nag at me. It would be so much cleaner if there was a way to guarantee completion after a single round. That's what was on my mind as I walked home from work yesterday, anyways.

Then it occurred to me... quantum computers are able to better coordinate in a lot of esoteric cases... maybe this is one of those cases?

Playing Around

The approach I took to solving this problem was... let's call it informal. I just made a bunch of guesses about what the solution would probably look like, and then toyed around.

I knew that the circuit I was looking for had to satisfy two properties:

- Symmetry. The same gates had to be applied to each side. Anything that happened to the A1 and A2 wires had to happen to the B1 and B2 wires.

- Anti-correlation. The output had to have no amplitude in the states where A1 and B1 agreed.

I guessed that the solution would probably start with each side making a Bell pair (because, let's be honest, every distributed quantum algorithm starts by making bell pairs). Then they'd probably have to swap half of their pairs, and do... something? With that in mind, I started up my quantum circuit inspector and began dragging gates around (you can try it from jsfiddle; source is on github). After about ten minutes I found a solution.

Solution

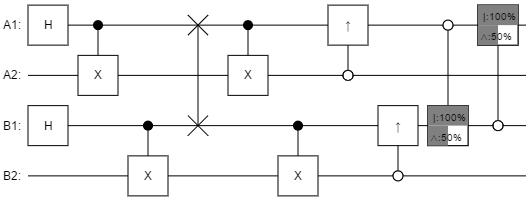

Here's the circuit I found:

Reading the circuit from right to left, each side should:

- Make a bell pair (requires quantum system).

- Swap half of the bell pair for the other side's corresponding half (requires quantum network).

- Do a controlled-not.

- Do a controlled-half-not in the opposite direction.

- A1 and B1 now disagree in all cases. Measure away.

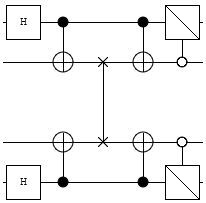

Here's a cleaned up circuit diagram, which better shows the symmetry:

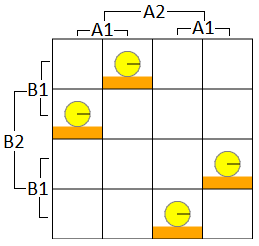

And here's a diagram of the amplitudes making up the final state, with cells where A1 and B1 agree never getting any amplitude:

The above solution is completely impractical in practice, what with the not being able to make quantum computers thing. But, if we pretend noise isn't a thing that exists, it is 100% guaranteed to always finish after just one round and that's what the goal was. Another nice property the above solution has is that it only requires one qubit exchange. The classical algorithms expect you to send at least two bits on average.

So... if you had billions of symmetry breaks to perform (you don't), and qubits were just as cheap as bits to send and store (they're not), and we hoped with all our might (...okay?), this might just be more cost-effective overall.

Worked Solution

Let's actually go through the solution in detail, tracking the state of the system as it progresses through the circuit. We'll ignore factors of $\sqrt{2}$ to make things slightly simpler.

The initial state is:

$\left| 0000 \right\rangle$

The first thing each side does is create a bell pair. This causes the first two and last two qubits to be in a uniform superposition of both-on and both-off:

$\left| 0000 \right\rangle$

$\rightarrow_{bell} (\left| 00 \right\rangle + \left| 11 \right\rangle) \otimes (\left| 00 \right\rangle + \left| 11 \right\rangle)$

$= \left| 0000 \right\rangle + \left| 0011 \right\rangle + \left| 1100 \right\rangle + \left| 1111 \right\rangle$

Now the sides each send their second qubit to the other, effectively swapping their second qubits (this is the only communication step):

$\left| 0000 \right\rangle + \left| 0011 \right\rangle + \left| 1100 \right\rangle + \left| 1111 \right\rangle$

$\rightarrow_{swap} \left| 0000 \right\rangle + \left| 0110 \right\rangle + \left| 1001 \right\rangle + \left| 1111 \right\rangle$

Next the sides do a controlled not from their kept qubit to the qubit they received, toggling the received qubit whenever the kept qubit is 1:

$\left| 0000 \right\rangle + \left| 0110 \right\rangle + \left| 1001 \right\rangle + \left| 1111 \right\rangle$

$\rightarrow_{cnot} \left| 0000 \right\rangle + \left| 0111 \right\rangle + \left| 1101 \right\rangle + \left| 1010 \right\rangle$

Finally, they apply a square-root-of-not a.k.a. beam-splitter a.k.a. 90-degree X rotation gate (sends $\left| 0 \right\rangle$ to $(1-i) \left| 0 \right\rangle + (1+i) \left| 1 \right\rangle$ and $\left| 1 \right\rangle$ to $(1-i) \left| 0 \right\rangle + (1+i) \left| 1 \right\rangle$) to the kept qubit whenever the received qubit is 0:

$\left| 0000 \right\rangle + \left| 0111 \right\rangle + \left| 1101 \right\rangle + \left| 1010 \right\rangle$

$\rightarrow_{split1} ((1-i) \left| 0000 \right\rangle + (1+i) \left| 0010 \right\rangle) + \left| 0111 \right\rangle + \left| 1101 \right\rangle + ((1-i) \left| 1010 \right\rangle + (1+i) \left| 1000 \right\rangle)$

$= (1-i) \left| 0000 \right\rangle + (1+i) \left| 0010 \right\rangle + \left| 0111 \right\rangle + \left| 1101 \right\rangle + (1-i) \left| 1010 \right\rangle + (1+i) \left| 1000 \right\rangle$

$\rightarrow_{split2} (-i \left| 0000 \right\rangle + \left| 1000 \right\rangle) + (\left| 0010 \right\rangle + i \left| 1010 \right\rangle) + \left| 0111 \right\rangle + \left| 1101 \right\rangle \\ + (-i \left| 1010 \right\rangle + \left| 0010 \right\rangle) + (\left| 1000 \right\rangle + i \left| 0000 \right\rangle)$

$= (i-i) \left| 0000 \right\rangle + (1+1) \left| 1000 \right\rangle) + (1+1) \left| 0010 \right\rangle + (i-i) \left| 1010 \right\rangle) + \left| 0111 \right\rangle + \left| 1101 \right\rangle$

$= \left| 1000 \right\rangle + \left| 0010 \right\rangle + \left| 0111 \right\rangle + \left| 1101 \right\rangle$

$= (\left| 1 \_ 0 \_ \right\rangle + \left| 0 \_ 1 \_ \right\rangle) \otimes (\left| \_ 0 \_ 0 \right\rangle + \left| \_ 1 \_ 1 \right\rangle)$

As can be seen above, in the final state the first and third qubits (of which each side has one) always differ.

Existing Work

Given that there are lots of papers on things like Fair Distributed Quantum Coin Flipping, which is like symmetry breaking except some of the participants aren't trustworthy, it's definitely already known that quantum networks can do a two-node symmetry break with a single qubit exchange. Unfortunately, I can't link to one of those papers because I can't find them! In physics, symmetry breaking means something different and those results are swamping out everything else when I search for quantum symmetry breaking algorithms.

Summary

Quantum computers connected by a quantum network only require a single exchanged qubit pair to perform a perfect symmetry break.