When you want to send classical information, but are doing so over a quantum communication channel (one that can transmit qubits), you're normally limited to sending 1 classical bit per sent qubit. How inconvenient.

However, there is a caveat to that limitation. If the sender and receiver happen to share a bell pair, they can consume said bell pair to pack 2 classical bits into a single qubit in a process called superdense coding. In a previous post, I talked about how this is like "storing bandwidth".

In this post, I'm going to go one step further. Instead of consuming previously shared bell pairs, we'll be making them on the fly and thereby doubling the classical information flow in one direction... by sending quantum information in the opposite direction.

A Field of Swaps

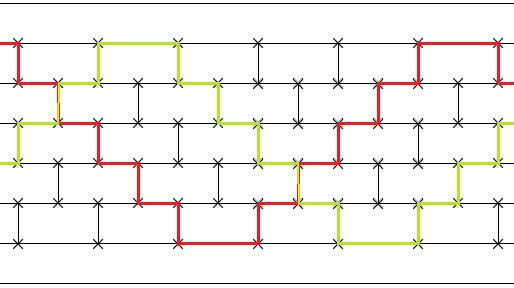

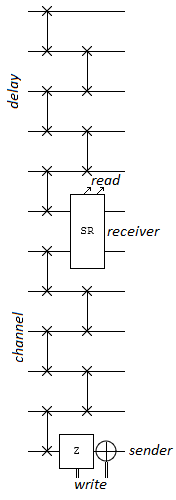

Suppose you have a quantum circuit where the top and bottom are separated by a large field of alternating swap gates. Anything introduced at the top will get swapped downward and downward and downward until it hits the bottom. Conversely, things introduced at the bottom get swapped upward until they hit the top:

In the above diagram, you can see two values bouncing back and forth, up and down, between the outer borders of the swap field. This allows the upper area to communicate with the bottom area. The field of swaps will be our quantum channel, and we will try to send lots of classical information over it in one direction. We'll arbitrarily say that the sender is the area below the swap field, and so the receiver is the area above the swap field. They are only allowed to mess with the field's outer-most wire on their side.

The easiest way to send classical information is for the sender to toggle its communication wire whenever there's a 1 to send, while the receiver repeatedly measures and resets its communication wire to 0. The sent bits will gradually swap from the bottom to the top, where they get consumed.

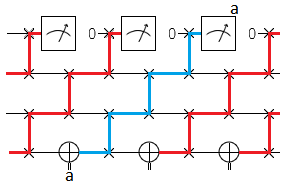

Here's a diagram of the process:

In the diagram, you can see that the classical bit $a$ determines whether or not the bottom wire gets toggled from off to on in the second time step. Then the swap gates move $a$ up, and up, and up, and then into the top wire. There it gets measured by the receiver. The receiver also resets the wire to be off, so as to avoid interfering with future bits being sent.

Unused Area

Look back at the previous diagram. Do you see the waste? Half of the horizontal wire sections are unused!

The reason those wire sections are unused is because they correspond to signals travelling in the opposite direction, from the receiver to the sender. We only care about sending information the other way.

Classically speaking, there would be no cost to leaving the return path idle. Sending information from B to A isn't going to help you send more information from A to B (well... I guess you could be sending information amenable to some sort of adaptive compression scheme, but let's assume we're sending incompressible information like coin flips).

Quantumly speaking (i.e. the case we're in), we can use the return path. We can use it to generate bell pairs, which we can then use for superdense coding.

Superdense Diagrams

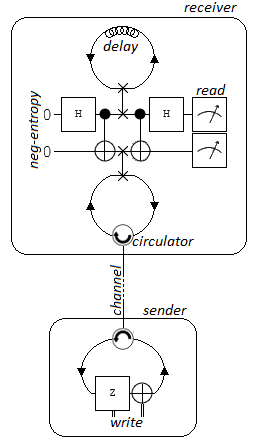

Assuming we go with the superdense encoding approach, what will the circuit look like? Well, the two sides will be much busier. The sender has to conditionally toggle and conditionally phase-toggle the bottom wire between each swap. The receiver has it even worse: between every swap they have to generate a bell pair, store one bell pair part locally and queue it for later, swap the other part for the qubit coming in from the receiver, retrieve the bell pair part that goes with the received qubit, and do a bell basis measurement. Phew!

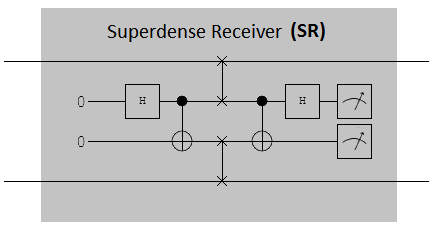

To make the circuit a bit more understandable, lets define a gate (the SR gate) to encapsulate most of the receiver work:

The above gate has the interesting property of outputting what it should later be given as input. It consumes some entropy to initialize two zero qubits, entangles them into a bell pair, swaps that pair for the incoming bell pair, then superdense-decodes the classical information that pair held.

It's important that each bell pair ends up matched back together. If they get out of order or off-by-one'd due to one part taking a trip to the sender and back, and get matched up with the wrong corresponding part, the message will get garbled. Fortunately there's an easy trick to keep the parts matched up: just copy-paste the swap field to also be above the receiver! The bell pair signals will head out, reach the opposite side, get operated on, bounce back, and meet back at the middle at the same time because we used a field with the same number of swap gates.

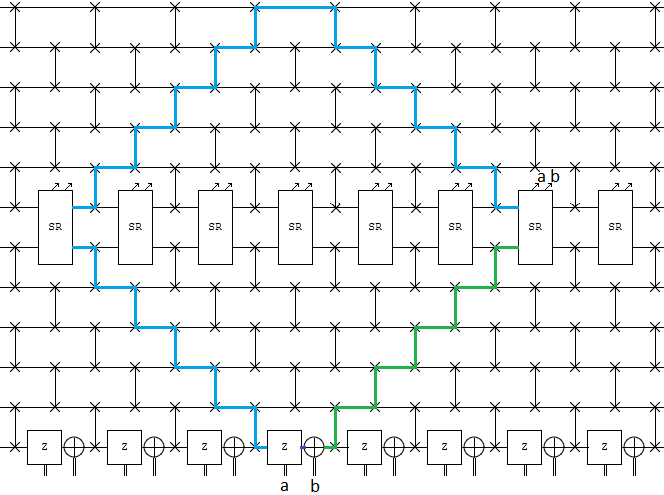

Here's a diagram of what the solution using superdense coding looks like:

In the above diagram, you can see that the bell pair generated in the second time step is what is used to send the classical bits $a$ and $b$. Actually writing out the full state of the system at each step is left as an exercise for the reader.

That diagram looks really busy, but it's just the same thing repeated over and over again. There's the receiver part, the sender part, the quantum channel between them, and the fake quantum channel we're using as a delay queue:

Instead of seeing it as a circuit, we could interpret the pieces as hardware components that apply their effect many times per second. You'd have a long cable for the channel, with a sender widget on one end and a receiver widget on the other:

Looked at that way, it almost looks practical! We'd need to be able to consistently perform bell basis measurement on entangled photons, hold photons coherently for tens of milliseconds, circulate them, time their arrival very accurately, and maybe a few more unsolved challenges I'm not even aware of because I'm not a hardware engineer (is optical fiber even a two-way quantum channel?)... but all that aside, we could potentially conceivably maybe actually use this to increase bandwidth in the real world! Awesome!

(And this time, I know someone didn't beat me to the punch by half a century and discover this in the 70s. Superdense coding was only discovered in the 90s. They probably only beat me to the punch by two decades. Success!)

Summary

You can double the classical capacity, in one direction, of a two-way quantum channel by using the other direction to create bell pairs to fuel superdense coding.

Unfortunately, the same trick doesn't work with quantum teleportation.