Two weeks ago, there was a post on Hacker News about a paper by Younes et al.. The paper claims to provide a polynomial time quantum algorithm for 3-SAT, an NP-complete problem.

The comments on the post are typical: optimists talking about how amazing this could be, pessimists warning others that this kind of paper is almost always wrong, and agnostics complaining that it's unfair to judge the paper before even looking at it.

So... does Younes' algorithm work?

The paper is simple enough and clear enough that I can definitively say: no. Since I've always enjoyed Scott Aaronson explaining obvious surface flaws, let's go over why. (I commented on the post at the time, but I can explain better here.)

The Algorithm

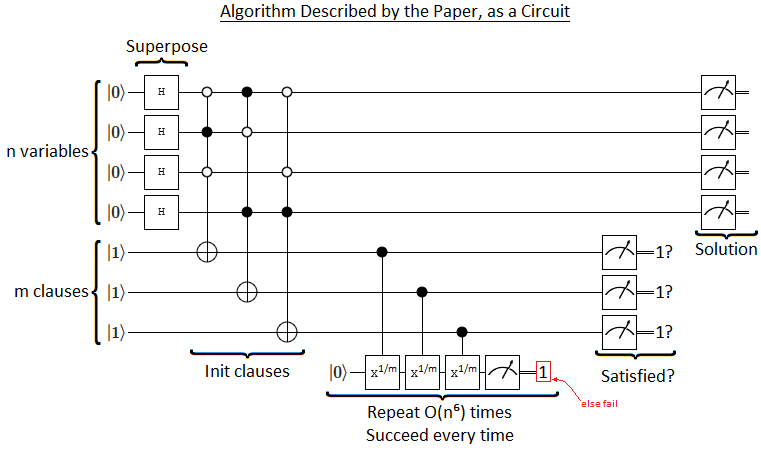

The underlying idea behind Younes' algorithm is to eat away at the amplitudes of variable assignments that don't satisfy all of the clauses. The algorithm creates a uniform superposition of solutions, rotates a qubit so its OFF-ness is entangled with the assignments and related to how many clauses are satisfied, then measures that qubit. If the measurement doesn't look promising, the algorithm retries; otherwise it repeats the rotate-and-measure check enough times to be sure of itself before returning an answer.

The following circuit diagram summarizes the algorithm:

Normally, this is where I would start explaining the details of each gate and pointing out some simplifications that were missed.... but that's not necessary. Understanding the problem doesn't require knowing what exactly an $X^\frac{1}{m}$ gate does; it's all about the measurements.

The Problem

Quantum algorithms are supposed to get their answer-finding power from their unfair ability to destructively interfere wrong answers, but Younes' algorithm is not doing that. In particular, notice that while the hard repetitive work is being done, nothing is happening to the qubits storing the superposition of variable assignments. Mixing the amplitudes of possible assignments, so they can destructively interfere, requires operating on those qubits.

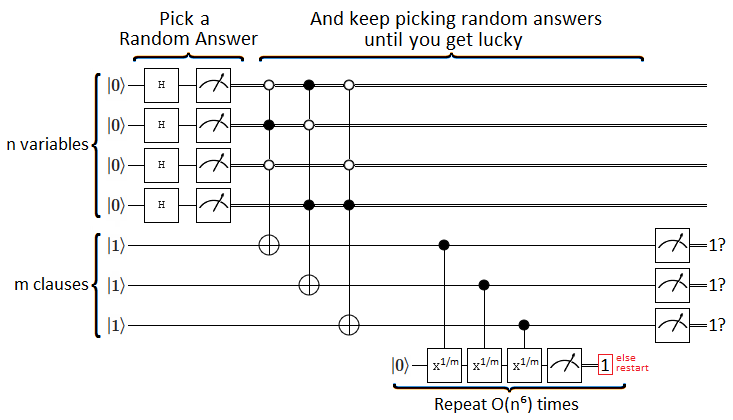

To see what's actually happening, we need to make a quick tweak to the circuit. Because the variable assignment qubits aren't being used during the hard work, there's no need to wait to measure them all the way on the right side of the circuit. In fact, because controls and measurements commute, we don't even have to wait for the clause qubits to be initialized. We can measure the assignment qubits right after putting them into superposition, without changing the expected behavior of the circuit! The result of doing that is this:

Oh. They're just post-selecting. When you pick a non-satisfying answer, the repeatedly-rotate-qubit-and-measure check causes you to restart (usually). When you pick a satisfying answer, you pass the checks after $O(n^6)$ work and finish.

The mistake Younes et al. made is forgetting to include the cost of all those failures and retries in their runtime; they only counted the successes. But if exactly one out of the $2^n$ possible variable assignments satisfies all of the clauses, then the expected number of retries before that assignment is found and the algorithm can return "Satisfiable!" is $\Omega(2^n)$.

For unsatisfiable instances, the expected number of retries gets even worse. My rough estimate is $2^{\Omega(n^6)}$ expected retries, based on the fact that most assignments should satisfy a constant fraction of the clauses so it's like winning $n^6$ bounded-bias coin flips.

To get a grasp on the running time in practice, let's consider an instance with $1000$ variables, $1000$ clauses, and no satisfying assignment. To get an upper bound on the expected number of retries needed to trigger a false positive that allows the algorithm to terminate, we'll assume there's an assignment that matches $999$ out of the $1000$ clauses and it keeps being picked.

The probability of that best-case assignment passing a single check is $\sin^2 \parens{\frac{\pi}{2} \frac{999}{1000}} \approx 99.99988\%$. Pretty good. But the probability of passing that check a quintiliion times in a row is so small that you need SI prefixes introduced in the mid-1960s to describe how many zeroes you'll be writing after the decimal point before getting to the actually useful digits. So we might end up retrying a lot.

Summary

If we didn't have to pay for retries, if we were working in PostBQP instead of BQP, then Younes' algorithm would run in polynomial time. But we do have to pay for retries, so it doesn't. Postselection is not free. Quantum suicide is never the answer.

Update

In response to the paper authors' comments below, I made a followup post that supports my conclusion by simulating the algorithm.

Comments

This is a really accessible critique of a difficult subject. Kudos.

We would like to thank you for taking time to read our paper and provide the above comments. However, we do believe that your analysis is mistaken in some important ways, as follows:

1. The system comprises four sub-systems (variables|A_x>, clauses|C_x>, temporary qubits|mu_max>,target qubit |ax>) which get entangled with each other. It is not then true to say that "nothing is happening to the qubits storing the superposition of variable assignments". The entanglement means that affected one part of the system affects the whole.

2. In particular, it is not correct to say that the measurements of the variable assignments can be brought forward to the start of the algorithm. The manipulation of the entangled target qubit involves measurements, and not purely control -and so this part of the algorithm will not commute with the measurement of the variable assignments. This would only work if the variable subsystem were independent of the rest, which it is not.

3. You leave out from your analysis the addition of the extra temporary qubits |mu_max> which allows us to amplify the probability of success in the reading of the target qubit. We show that with the addition of these extra qubits we can reduce the number of restarts to a polynomial.

With best regards

Ahmed Younes & Jonathan Rowe

Thanks for your comment. I will look at the paper again and justify/realize-the-error-of my points at a more basic level.

I'm pretty sure that the operations on the clause and introduced ancilla bits can't affect the expected value of measuring the variable bits, because doing so would allow you to violate the no signalling theorem and perform FTL communication. But that's a bit too high level of a justification when low level issues like whether or not a given measurement can affect a given part of the state is being debated.