This month, a team of scientists published a paper about an experiment related to the quantum zeno effect. There were lots of pop science articles about it and, of course, they caused as much confusion as clarity.

One of the pervasive misconceptions people have about quantum mechanics is that "observation" means "watching", i.e. a conscious human looking in the general direction of an experiment. It's important to clear up this misconception when talking about the quantum zeno effect, because it uses repeated measurements (a.k.a. observations) to control a quantum system.

Journalists worry about their audience taking the wrong message away, so they are careful to clarify this kind of oft-misunderstood detai- Hahaha, of course not. Instead of informing people, let's use analogies that reinforce their existing misconceptions! Turns out "Atoms Won't Move While You Watch" because of the Quantum "Weeping Angel" Effect. And don't forget to quip about watched pots refusing to boil!

*Sigh*

I'm exagerating a bit, and not all of the coverage was bad, but for the purpose of feeling clean again let's discuss the quantum zeno effect in more detail.

Controlling With Measurement

When a quantum state is measured twice in quick succession in the same basis, it doesn't have much time to change between the two measurements. This prevents it from getting very far from the state it was just measured to be in. So the second measurement has a very high probability of getting the same result again, and thus collapsing the quantum state back onto the same measured state that the first measurement did.

If you do a third measurement very soon after the second measurement, the same thing happens again. The quantum state will be close to where the second measurement collapsed it, you'll get the same result a third time with high probability, and re-collapse the quantum state onto the same original measured state yet again. As long as you measure fast enough and frequently enough, you can keep this same-result-with-high-probability chain going indefinitely.

To understand what's happening in mathematical detail, let's look at what happens when we pass photons through a series of slightly rotated polarizer filters.

For our purposes here, passing a photon through a polarizer filter is a measurement of the photon's polarization. If the photon's polarization matches the filter, it goes right through without being affected. If the photon's polarization is perpendicular to the filter's direction, the photon is absorbed. Photons with intermediate polarization directions, between parallel and perpendicular, pass through probabilistically. More exactly, a photon whose polarization deviates from the filter's by an angle $\theta$ will pass through the filter with probability $\cos^2 \theta$ (and, after passing through, the photon's polarization will be parallel to the filter's).

Suppose we have a source of horizontally polarized photons, like sunlight reflected off of a lake at a shallow angle. If we pass the horizontally polarized light through a vertical filter, it will all be blocked. However, if we first pass the photons through a diagonal polarizer, then some of the light will get through. Assuming the diagonal polarizer is 45° off of horizontal, it will allow $\cos^2 45° = 50\%$ of the horizontally polarized photons to continue towards the vertical polarizer. Another half of the photons will be lost at the vertical polarizer, because they were diagonally polarized (45° off of vertical) by the diagonal polarizer.

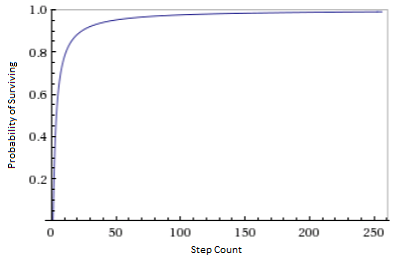

By using more and more filters, with finer and finer angular steps from horizontal to vertical, we can let through more and more light. If we have a series of nine polarizers stepping from horizontal to vertical in increments of 10°, then $(\cos^2 10°)^9 \approx 75\%$ of the photons will make it through. If we use ninety polarizers, and 1° steps, the survival rate increases to $(\cos^2 1°)^{90} \approx 97\%$ of the photons.

In general, with $n$ polarizer steps, the probability of an incoming horizontally-polarized photon surviving the whole series of filters (and coming out vertically polarized) is $(\cos^2 \frac{90°}{n})^n$. As $n$ increases, the survival probability converges towards certainty:

This is really surprising. We're rotating the polarization by filtering it! And we're not losing any photons in the process!

Before I'd read about the zeno effect, I would have never expected this to work. Obviously the filters would have to remove a non-negligible number of photons, otherwise how could they do any steering? Surely there'd be some non-zero proportion of necessary loses here.

Nope. I'd have been dead wrong. The zeno effect is precisely the fact that you can steer states, with negligible loses, by filtering or measuring.

(Side rambling: My guess would have been that you could save at most $\frac{1}{e}$ of the photons, because that's what $(1-\frac{1}{n})^n$ limits to. Actually, $(cos \frac{1}{n})^{2n^2}$ also limits to $\frac{1}{e}$ and that's quite similar to the actual expression. Interesting. But still wrong.)

It's common to state the zeno effect in terms of an unchanging measurement stabilizing a time-varying state, instead of vice-versa like in the polarizer example (where a time-varying measurement causes a stable state to change). The example could be made "more typical" by using a polarization rotator material to make the photon's polarization rotate, then using closely spaced horizontal polarizer filters to hold the state stable against the rotation... but I think you get the idea. The underlying math is the same in both cases.

Summary

You can hold a time-varying quantum state stable, and even steer it, by frequently measuring it.

The quantum zeno effect is a good counter-example to the idea that measurements unavoidably perturb quantum systems; they unavoidably affect the system, but don't have to perturb it.