Back in 2014, a preprint titled "The quantum pigeonhole principle and the nature of quantum correlations" was posted to arXiv by Y. Aharonov et al. This month, the paper was published for real in PNAS. The media picked up on the result both times, resulting in some choice quotes:

if you check the paths of any pair of the three original electrons, the detector will show no deflection has happened. In other words, you can have three pigeons and two boxes, and yet no two pigeons are ever found in the same box. A linkage must exist, because it’s as if the particles know the other is there, and avoid each other. - New Scientist (2014)

"This is at least as equally profound, if not more profound [than the EPR paradox].", [one of the authors] says. - physicsworld (2014):

The phenomenon suggests there is a new type of quantum reality that impacts all matter. - Daily Mail (2016)

This discovery could change the way we think about quantum physics, forever. - Telegraph (2016)

That's... quite the hyperbole. And some of it quoted straight from the authors' mouths!

Physicists had more reserved, and mixed, reactions:

There has been considerable interest in a recent preprint describing an effect named as the “Quantum Pigeonhole Principle”. [...] a quantum mechanical measurement would imply that no more than 1 of the n objects is contained in any of the m boxes, even though n > m. - Alastair Rae and Ted Forgan

some of the conclusions in the paper are ambiguous in the sense that they depend on the precise way one defines correlations, and that the “first experiments” the authors suggest has little if any bearing on their main theses. The far-reaching conclusions the authors reach seems, therefore, premature. - B. E. Y. Svensson

Reading further into the argument, it turns out that the first measurement is an imaginary measurement -- it isn't actually performed, but we imagine how it could have come out if it had been performed. - Stephen Parrott

My personal opinion is that the paper's details are correct, but that the authors' framing of those details is off-the-wall ridiculous. To justify that opinion, let's get into what the paper actually claims. (More specifically, what the preprint claims. Since that's what I read.)

Think of it as a Game

My interpretation of Aharonov et al's main result is as a strategy for consistently winning a game. A game that, classically, couldn't be won consistently. But quantumly it can be.

Of course the idea that quantum strategies can be superior to classical strategies isn't new. There's lots of games with a known quantum advantage (see Brassard et al's "Quantum Pseudo-Telepathy" paper for several examples), and the general concept dates back to the 1960s (i.e. the Bell inequalities). So what's new is the particular game we're winning more often.

So what's the game? Well, it involves three (or more) coins and progresses as follows:

- You set up the coins. Each coin has to be either heads or tails, and you get to pick. For example, you might pick "HHT".

- A referee makes a secret parity measurement. You give the coins to a referee, they secretly pick two, and note down if the chosen coins agreed (HH/TT) or disagreed (HT/TH)

- You decide whether or not to restart. The referee gives the coins back to you for inspection. You check them out, then announce either "keep" or "restart". If you said "restart", we throw away everything and go back to step 1.

- You win if the coins disagreed. When you finally say "keep", you win if the referee noted "disagree" back in step 2.

There's really not much to the game, classically speaking. I mean, step 3 seems kind of... pointless? Who cares that you got the coins back and have the option of restarting? It's not like you're learning any new or relevant information to base that decision on.

Optimal classical strategies for this game win 2/3 of the time. Here's one: randomly pick between "THH", "HTH", or "HHT" and never restart. Simple. You win when the referee's parity measurement included the disagreeing coin, which happens 2/3 of the time.

The reason you can't win 100% of the time is why the paper is called what it is: the pigeonhole principle. There's three coins and two boxes (H and T), so two coins must end up in the same box and create a chance to lose. You want the coins to all have disagreeing values, but there's not enough values!

If only we won when the coins agreed, this would all be much easier. We could just wait for a state like "HHH", and know for sure that the referee measured "agree" because every pair agrees. If only there were some way to always toggle the parity touched be the referee... then we could look for all-agree states...

Quantum Game, Quantum Strategy

In order to make quantum strategies possible, our game needs qubits instead of coins. Instead of using classical 2-level systems, we'll be using quantum 2-level systems. Otherwise it would be impossible to place things in superposition, or perform unitary operations.

Using qubits instead of coins opens up some possibilities. There are better strategies now. Strategies that win 100% of the time. The paper describes one such strategy, which I've translated into a circuit diagram for the five coin game:

In words, the winning strategy is to:

- Put each of the qubits into the $\ket{0} + \ket{1}$ state.

- Let the referee perform their secret parity measurement.

- Rotate each qubit by 90° around the X axis.

- Retry until the qubits measure as all ON or all OFF.

Winning with this strategy might take awhile when there's a lot of coins (e.g. with five coins each run has a $\frac{1}{2^4}$ chance of working, so you expect ~16 restarts), but you're guaranteed to eventually win.

Why does it work?

There are a few background facts you need to know in order to understand why the described quantum strategy wins the game.

First, performing a parity measurement on two qubits can entangle them. If you have two qubits in the state $\ket{0} + \ket{1}$ and you copy their parity into a scratch qubit, as the referee does in the game, the system will go from the state $(\ket{0} + \ket{1})(\ket{0} + \ket{1})\ket{0} = \ket{000} + \ket{100} + \ket{010} + \ket{110}$ to the state $\ket{000} + \ket{101} + \ket{011} + \ket{110}$. Measuring the scratch qubit then drops the initial two qubits into either the 'even-parity' state $\ket{00} + \ket{11}$ or the 'odd-parity' state $\ket{10} + \ket{01}$. Those are entangled EPR states.

Second, for both the entangled even-parity and odd-parity states, rotations around the X axis rotate the parity instead. If you're in the even-parity state $\ket{00} + \ket{11}$ and you hit the first qubit with a NOT gate (i.e. rotate it 180° around the X axis), you end up in the odd-parity state $\ket{10} + \ket{01}$. The same thing happens if you hit the second qubit with a NOT gate. And hitting either of them with a further NOT gate will return you to the even-parity state. This also works for partial rotations, which is crucial. Hitting both qubits with a 90° rotation around the X axis adds up to one full 180° NOT of the parity.

Third, qubits in the initial unentangled state aren't affected by X rotations. The Bloch sphere point corresponding to the state $\ket{0} + \ket{1}$ is on the X axis. Points on an axis aren't affected by rotations around that axis.

Got all that? When the referee performs a parity measurement on the state we crafted, they are actually entangling the two qubits they touched. We don't know the parity of that entanglement, but we can toggle said parity by rotating the touched qubits around the X axis. And rotating the wrong qubits can't hurt, because the untouched qubits are in a state not affected by this particular rotation.

So what's happening is:

- The two qubits touched by the referee end up in the even-parity state $\ket{00} + \ket{11}$ or the odd-parity state $\ket{01} + \ket{10}$.

- Rotating every qubit by 90° doesn't affect the untouched qubits, but inverts the parity of the touched qubits. If the referee wrote down "disagree", the two touched qubits now agree. If the referee wrote down "agree", the two touched qubits now disagree.

- When we measure the qubits and they all return the same result, we know the parity of every pair ended up "agree". And since we inverted the parity of the pair the referee measured, the referee must have measured "disagree".

The key point here is that there are states where all the parities are even, but there aren't any states where all the parities are odd (assuming we used at least 3 coins/qubits, of course). The pigeonhole principle prevents a watch-out-for-even-parities strategy from working consistently, because there's always at least one even parity. But the pigeonhole principle is not an obstacle for a watch-out-for-odd-parities strategy, because there's no law against stuffing arbitrarily many pigeons into one box (uh... you know what I mean).

This fundamental difference between even-parity and odd-parity (i.e. that there exist all-pairs-even states but not all-pairs-odd states) is what forces us to go quantum and use entangled-half-rotation shenanigans. Classically, there's no way to consistently toggle the parity measured by the referee.

Caveat

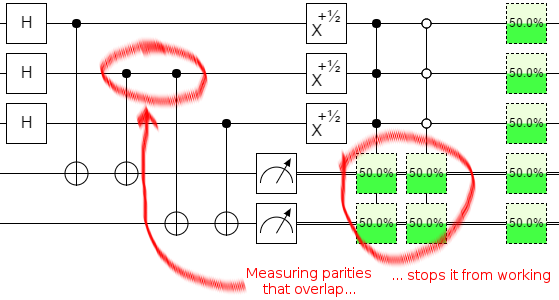

Before moving on to interpretation, I want to mention a very important caveat on all this: the strategy stops working if the referee measures more than one parity. Non-overlapping parity measurements will work fine, but things break as soon as there's any overlap:

When there's an overlapping parity measurement, the qubits do still end up entangled due to the referee's meddling. But now the entangled state involves three (or more) qubits instead of two. That weakens the entanglement, and X-rotations of the individual qubits no longer operate on the parity in the same way.

This is a very important caveat, because actually verifying that the "pigeonhole principle was violated" would involve overlapping parity measurements.

Also I think this caveat means that the paper's experimental prediction, that you can pass three electrons through two paths and find that when post-selection succeeds there was no deflection (because they weren't "in the same box"), is wrong. Each deflection is a parity measurement, and they overlap, so... it won't work. You'll see deflection even after post-selecting. (Then again, weak measurement is extremely flexible and I'm no physicist...)

Interpretation

The authors of the paper go waaay over the top when interpretating what this all means. But let me give a classical analogy for what's going on.

Suppose we tweaked the coin-parity game so that, when the referee measures a parity, they have to flip one of the touched coins. Now it's easy to win 100% of the time classically: restart until you see a state where all the coins agree. Even if the coins are assigned randomly and you don't get to see them in step 1, you can still win 100% of the time.

By the logic the paper uses to conclude that the pigeonhole principle doesn't apply to quantum states, the above paragraph proves the pigeonhole principle doesn't apply to classical states. Alternatively, having a clever indirect way of knowing if a single unknown parity check came up odd doesn't quite equate to "all the parities must have been odd and reality is a lie!". And the fact that overlapping parity checks, the ones that would actually confirm an impossible pigeonhole violating state, prevent the strategy from working is kind of a big hint.

That's really all there is to it. The paper's strategy is clever, sure. But concluding the pigeonhole priciple was violated because you cleverly discarded all the cases where coins were caught in the same state? That's just wrong. And describing this as world-view shattering? That's downright absurd.

Summary

Measuring the parity of two qubits can entangle them. You can rotate the parity of that entanglement by rotating the individual qubits. This allows you to sometimes determine if a parity measurement was odd, by using the resulting entanglement to toggle the parity and watching for all-parities-agree states.

The way this paper was framed and presented by the media, and especially by the authors, makes me sad.