Update (May 2016): This post is quite vague on the details. The followup post Eve's Quantum Clone Computer spends more time on them.

Last month, YouTuber CGP Grey posted an edutainment video about the philosophical implications of transporters. One of the points he focuses on is whether teleportation works by creating a copy of you and killing the original.

In response to the teleportation video, MinutePhysics posted a follow-up video about quantum teleportation. The follow-up video points out that quantum information can't be copied, only moved, so if your identity somhow depends on quantum information then you don't have to worry about being duplicated(-then-killed).

This idea, that if our brains operate on quantum information then they are duplication-proof thanks to the no-cloning theorem, tends to come up whenever the is-teleportation-death question does (here's another example, on Quora). Which is a shame, because I think it's an invalid argument.

Why do I think that even quantum-computing brains may be cloneable? Because brains have to interact with the world.

Private Matters

The fundamental reason we can't clone an unknown quantum state comes down to the fact that measurements are dither-ish. The underlying state space is continuous, but measurement results are quantized and overwrite the measured state. For example, a photon's polarization can be horizontal or vertical or diagonal or anything in between. But a polarizer can only tell you if the polarization was along or against the polarizer's orientation, and in doing so the polarizer will force the photon's polarization to actually be either all along or all against.

That being said, quantum information that just sits there being uncloneable doesn't really do much. In order to have a visible effect on the world, the information has to get mixed into the environment. Qubits have to affect a measurement to matter.

If an uncloneable detail is crucial to your identity, you eventually have to actually use it. Otherwise it would have absolutely no effect on your behavior, ever (which is not very identity-defining-ish). But, when you do finally use that detail, you reveal its state and make it vulnerable to copying.

So technically all a brain-copier has to do is... wait.

Copying Process

Here is the basic strategy I have in mind for copying a quantum brain:

- Move into computer.

- Scan the brain, breaking it down into the necessary classical and quantum information.

- Make sure the $n$ qubits of identity-defining information are moved into a quantum computer.

- Track what's known about the state.

- Store a $2^n \times 2^n$ density matrix, initialized to the maximally mixed state, on an intractably powerful classical computer.

- Whenever an operation is applied to the identity-defining qubits, apply the same operation to the density matrix.

- Whenever an identity-defining qubits is measured, project the density matrix into the measurement's outcome.

- Arrange for new identity-defining qubits to be in known states (*see next section). Tensor them onto the density matrix when created.

- Simulate and wait.

- As the simulated brain interacts with the world and the identity-defining core, measurements of the identity-defining qubits and post-selections of the tracked density matrix cause the two to converge.

- As the gradual copying process runs, you can compute an upper bound on how much the tracked density matrix might deviate from the identity-defining state.

- Eventually the deviations will be small enough that we basically know the relevant quantum state. Alternatively, anything still not measured after a month probably doesn't affect who you are very much.

- Start printing copies!

- The tracked density matrix is your blueprint for the identity-defining quantum state.

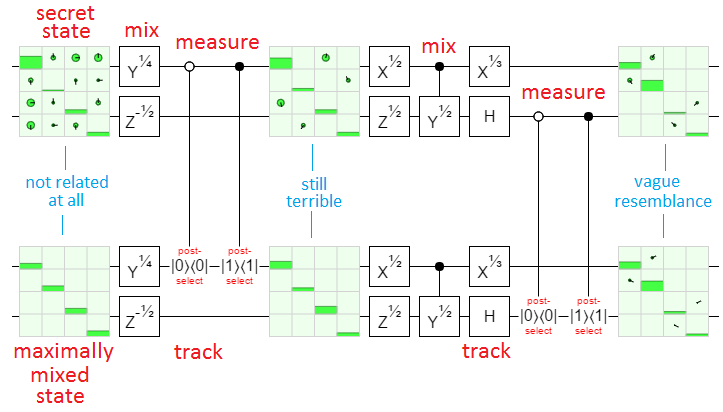

Here's an example circuit showing that, even with intermediate mixing operations, matching operations while post-selecting based on the measurement results does push the tracked state and the secret state towards each other:

The above diagram is a bit misleading, because the states it is showing are a weighted mix of the possible measurement outcomes. We care about the possible outcomes individually, not as a weighted group. Also I didn't explain why those controlled post-selections properly emulate a measurement. Still, I think it makes a good illustration. The individual possibilities look basically the same, just more pure.

I hope that explanation was clear enough, because now we're moving on to talking about situations where this gradual copying process won't work.

Countermeasures

There are several ways that quantum-computing brains could be resistant to the copying process outlined above. I'm going to cover two important ones: big identities and entangled identities.

Big identities are a problem because the copier I defined is using a classical computer to track what's known about the quantum state. Classical simulations of quantum states tend to be exponentially expensive. With just forty qubits of identity-defining information, we're talking yottabytes of storage and yottaflops of computation (thus the "intractably large" note in the previous section).

It might be possible to find a state-tracking algorithm (possibly a quantum one) that avoids the cost blowup, but the problem of finding a state that matches given measurements throughout a computation sounds awfully NP-complete to me.

Entangled identities cause trouble because external entanglement is impossible to copy without help. For example suppose, for the sake of argument, that brains exchange a few thousand EPR pairs whenever they meet. Then, when meeting again, they prove their identity by answering challenges like "What will I get if I measure $Q_{231}$ along $D$?". These identity-validating EPR pairs a) can't be created without the help of an external entity, b) are quite long-lived, and c) are continuously recreated.

A constant stream of new unknown states being incorporated into the identity will prevent the tracked density matrix from converging on purity. Entanglement with an external system (such as another brain) makes the unknown-ness unavoidable, and will prevent step 3 of the copying process from terminating. (If only the other brains were also in the simulation...)

So a quantum-computing brain can be resistant to copying, but there's a lot more to the story than just "No Cloning Theorem says No.".

Summary

Even if your identity is made of quantum information, the need to touch that information in order for it to affect your behavior may allow for eventual duplication.

Making a state hard to duplicate while interacting with the outside world via an untrusted quantum computer is an interesting cryptography problem. See: quantum copy-protection and quantum money.

Updated (Apr 06, 2016): Added the example circuit diagram, and re-worded the 'copying process' section.

Updated (Apr 09, 2016): Re-worded some statements in an attempt to remove ambiguity between eventualy touching a specific qubit and eventually revealing unknown details.