Last post, I tried to explain an interesting consequence of the fact that interactions with the world can reveal the current state of a quantum system.

I framed the post around the hypothetical of duplicating a brain despite the brain containing quantum information. I pointed to a couple examples of people saying it would be impossible to do that, since the No-Cloning Theorem prevents the duplication of unknown quantum states. Then I tried to explain a copying algorithm based on moving the brain into a quantum computer and inferring its state by recording any measurements the brain decided to perform.

Anyways, I didn't explain the concept very well and took flak from people thinking I was claiming obviously-wrong things. So let's try this again, but slower.

Hold my Qubit

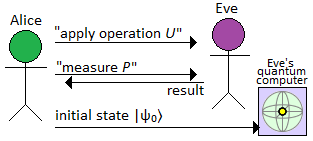

Suppose Alice has some quantum information, but is storing it on Eve's quantum computer.

Storing the information on Eve's computer is inconvenient. Whenever Alice wants to apply an operation or measure a qubit, she has to ask Eve to do it for her. Which is tedious. Also there's the fact that Eve could be snooping on Alice's state... but Alice figures the quantum-ness probably protects against that somehow. And Alice doesn't own a quantum computer of her own, so it's not like she has any other option.

Here's a diagram of the situation:

Eve, being Eve, wants to snoop on Alice's information. Specifically, she wants to make an eventual copy of Alice's state despite knowing nothing about the initial state and not daring to apply any operations Alice doesn't ask for. That sounds quite hard (what with the quantumness), but Eve is resourceful. And patient.

The no-cloning theorem guarantees Eve can't make a copy of the initial state $\ket{\psi_0}$. But Eve isn't focusing on $\ket{\psi_0}$; she wants a copy of any $\ket{\psi_t}$. Basically, Alice will be explaining some process that causes $\ket{\psi_0} \rightarrow \ket{\psi_1} \rightarrow ... \rightarrow \ket{\psi_t}$ but Eve wants to tamper with things so that $\ket{\psi_0}\ket{?} \rightarrow \ket{\psi_1}\ket{?} \rightarrow ... \rightarrow \ket{\psi_t} \otimes \ket{\psi_t}$ happens instead.

As long Alice only asks for unitary operations to be applied, she's safe from Eve's snooping. Rotating an unknown quantum state doesn't tell you anything about the state. But, whenever Alice asks for a measurement, Eve gets to see the result. Hmm...

Catching a Qubit

Suppose Alice is storing only a single qubit in Eve's computer. This case is trivial, because the jig is up as soon as the first measurement is applied. Any measurement will collapse Alice's state to one of two possibilities, and the measurement result will tell Eve exactly which possibility it was.

(Note: Eve's computer only supports single-qubit measurements in the computational basis. If Alice wants to perform weak measurements, or measurements in a different basis, she has to emulate them with a series of operations.)

Let's go over an example case where Eve ends up with a copy of Alice's state:

- Alice securely loads her state into Eve's computer.

- The initial state happens to be $\ket{\psi_0} = \frac{1}{\sqrt 2}\ket{0} - \frac{1}{\sqrt 2}\ket{1}$.

- Eve doesn't know $\ket{\psi_0}$, so she can't clone it.

- Alice asks Eve to hit the state with a Z gate.

- The state becomes $\ket{\psi_1} = \frac{1}{\sqrt 2}\ket{0} + \frac{1}{\sqrt 2}\ket{1}$.

- Eve still knows nothing, so no cloning can happen.

- Alice asks Eve to measure the qubit.

- The measurement result is "Off", which Eve reports.

- Eve knows that "Off" corresponds to the state $\ket{0}$.

- Eve initializes $q_{\text{copy}}$ to $\ket{0}$.

- Eve wins.

(Keep in mind that Eve didn't clone the original state of Alice's qubit. Eve cloned a post-measurement state, not the preceeding unmeasured state. That's why we aren't violating the no-cloning theorem.)

The single qubit case is kind of boring, as you can see. Eve never has partial information about the qubit; it's all or nothing. To make the situation less black and white, we need more qubits.

Analyzing a 2-Qubit System

Now Alice is storing two qubits, $q_1$ and $q_2$, on Eve's computer. This is a big step up from one qubit, because Alice can mix things up between measurements. Eve may never see a snapshot of the whole state.

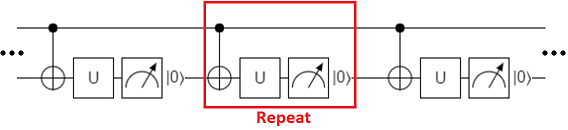

There's a lot that could be said about the 2-qubit case, but let's focus on one particular type of thing Alice can do: obscuring a value with a unitary operation. Specifically, Alice will repeatedly ask Eve to CNOT $q_1$ onto $q_2$, and to measure then clear $q_2$. However, to protect $q_1$'s value from Eve, Alice will apply a masking operation $U = \bimat{a}{b}{c}{d}$ to $q_2$ just before the measurement.

Here's a circuit diagram showing the operations Alice will ask Eve to apply over and over and over:

Will Eve be able to infer the value of $q_1$ by recording the measurements of $q_2$? To answer that question, we need to understand how $q_1$ is affected by the circuit. (Yes, it's affected despite only being used as a control.)

Suppose $q_1$ starts in the pure state $x \ket{0} + y \ket{1}$, so the system as a whole is in this state:

$$\ket{\psi_t} = x \ket{00} + y \ket{10}$$

Apply the CNOT. The new state is:

$$\ket{\psi_{t+1}} = x \ket{00} + y \ket{11}$$

Now apply $U$, advancing the state to:

$$\ket{\psi_{t+2}} = x a \ket{00} + x b \ket{01} + y c \ket{10} + y d \ket{11}$$

Lastly, measure $q_2$ and clear it. There are two possible output states, one for the OFF measurement outcome and one for the ON outcome:

$$\begin{align} \ket{\psi_{t+3,\text{OFF}}} &= \frac{x a \ket{00} + y c \ket{10}}{\sqrt{|ax|^2 + |yd|^2}} \\ \ket{\psi_{t+3,\text{ON}}} &= \frac{x b \ket{00} + y d \ket{10}}{\sqrt{|xb|^2 + |yd|^2)}} \end{align}$$

Those normalization factors are pretty gross. Let's ignore them by focusing on proportions instead of exact amplitudes. The proportional squared magnitudes $Q$ for $q_1$ being OFF to $q_1$ being ON are:

$$\begin{align} Q_t &= |x|^2:|y|^2 \\ Q_{t+3,OFF} &= |xa|^2:|yc|^2 \\ Q_{t+3,ON} &= |xb|^2:|yd|^2 \end{align}$$

Based on $U=\bimat{a}{b}{c}{d}$ being unitary, we know that $|a|^2=|d|^2$ and $|b|^2 = |c|^2 = 1 - |a|^2$. Also we know that $|x|^2 = 1 - |y|^2$. That lets us cut the number of variables needed to describe the proportions:

$$\begin{align} Q_t &= 1-|y|^2:|y|^2 \\ Q_{t+3,OFF} &= (1-|y|^2)|a|^2:|y| (1-|a|^2) \\ Q_{t+3,ON} &= (1-|y|^2) (1-|a|^2):|y|^2 |a|^2 \end{align}$$

By defining $r_u = \frac{|a|^2}{1-|a|^2}$, we can simplify even further:

$$\begin{align} Q_t &= 1-|y|^2:|y|^2 \\ Q_{t+3,OFF} &= (1-|y|^2) \cdot r_u:|y|^2 \\ Q_{t+3,ON} &= 1-|y|^2:|y|^2 \cdot r_u \end{align}$$

Our final simplification is to switch from odds $Q$ to log-odds $\tilde Q$. We'll take the logarithm of both sides of $Q$ and track the difference (let $s_u = \lg r_u$ for simplicity):

$$\begin{align} \tilde Q_t &= \lg |y|^2 - \lg(1-|y|^2) \\ \tilde Q_{t+3,OFF} &= \tilde Q_t - s_u \\ \tilde Q_{t+3,ON} &= \tilde Q_t + s_u \end{align}$$

So the effect of our circuit on $q_1$'s squared-magnitude log-odds is to either add or subtract a constant... Oh! We're performing a random walk in log-odds space, with a step-size of $s_u$!

The limiting behavior of the walk is not immediately clear. Normally a random walk's probability $p$ of stepping forward is constant, and whether or not the walk diverges is just a matter of checking that $p$ isn't 50%. But in our case $p$ changes as the walk drifts left and right; it depends on $\ket{\psi_t}$:

$$\begin{align} p &= |xb|^2 + |yd|^2 \\&= (1-|y|^2) (1-|a|^2) + |a|^2 |y|^2 \\&= \text{lerp}(|y|^2, 1-|a|^2, |a|^2) \end{align}$$

Okay, so the probability of stepping forward is a linear interpolation from $1-|a|^2$ to $|a|^2$, controlled by $|y|^2$. What does that mean?

Roughly speaking, $|a|^2$ corresponds to how much $U$ likes to toggle its input. When $|a|^2$ is near 0, $U$ is mostly-diagonal and tends to not toggle its input. OFF stays OFF, and ON stays ON. Around $|a|^2=0.5$ the toggling is completely unpredictable. When $|a|^2$ is near 1, $U$ is mostly-anti-diagonal and tends to always toggle its input. OFF and ON get swapped.

Recall that $|y|^2$ is just the probability of $q_1$ being ON. So, as $q_1$ transitions from mostly-ON to mostly-OFF, $p$ transitions from $U$'s toggly-ness to the complement of $U$'s togglyness.

We now have enough information to summarize whether the random walk's steps are biased positive-ward (towards ON) or negative-ward (towards OFF) for various cases. By taking into account both the probability $p$ of stepping along $s_u$ instead of against $s_u$, and the sign of $s_u$, we can chart whether the walk's bias is positive-ward or negative-ward in each case:

| Operation → State Bias ↓ ↘ |

Stable $|a|^2 = 1$$s_u = \infty$ |

Mostly Stable $|a|^2 \approx 1$$s_u >> 0$ |

Slightly Stable $|a|^2 > 0.5$$s_u > 0$ |

Random $|a|^2 = 0.5$$s_u = 0$ |

Slightly Toggly $|a|^2 < 0.5$$s_u < 0$ |

Mostly Toggly $|a|^2 \approx 0$$s_u << 0$ |

Toggles $|a|^2 = 0$$s_u = -\infty$ |

| OFF $p = 1-|a|^2$ |

N/A | ---- | --- | N/A | --- | ---- | ----- |

| Very OFF $p \approx 1-|a|^2$ |

---- | --- | -- | N/A | -- | --- | ---- |

| Slightly OFF | --- | -- | - | N/A | - | -- | --- |

| 50% ON $p = 0.5$ |

0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Slightly ON | +++ | ++ | + | N/A | + | ++ | +++ |

| Very ON $p \approx |a|^2$ |

++++ | +++ | ++ | N/A | ++ | +++ | ++++ |

| ON $p = |a|^2$ |

+++++ | ++++ | +++ | N/A | +++ | ++++ | N/A |

(Note: The corner N/As are due to those cases being impossible. They have 0 probability. The center N/As are due to the step size degenerating to 0 when $U$'s togglyness is 50%.)

The important thing to notice about the above table is that the bias is OFF-ward (negative) when the state is OFF-ish, and ON-ward (positive) when the state is ON-ish. In other words, the bias is always away from the origin. That means the random walk will diverge to one of the infinities; it won't keep coming back to the origin. Thus $q_1$ almost surely converges to ON or converges to OFF.

Based on the analysis we just did, Eve can succeed at making a copy of Alice's state by merely waiting long enough for the random walk to get far from the origin. But let's actually simulate what happens.

Simulating a 2-Qubit Inferrence

How can Eve track the state of Alice's system automatically, without knowing the exact state?

Here's a really naive idea: write down a list of all the possible states, and simulate applying Alice's requested operations to each of them. When Alice says to rotate a qubit around the X axis, go through every single entry in the list and apply that rotation around the X axis. When Alice says to measure a qubit, do the measurement on the real qubit then post-select every entry in the list to match the result. If the list entries are ever all in basically the same spot, that's Alice's state.

Of course we can't actually list all the possible quantum states, since there's uncountably many of them. But we can cover the state space as densely as desired, so that the true state is at most $\epsilon$ away from one of the entries in the list. (This is all horrendously inefficient, but let's ignore that for now.)

It's straightforward to write hacky code that generates possible quantum states and simulates how those states change as Eve forces them to track what's happening to Alice's state. We can even give a nice representation of the list of states, by plotting entries onto the Bloch sphere (although there's 2 qubits in the state, one is known thanks to the measurements; plot the other one).

If you write that hacky code, and set $U$ to be a 75-degree rotation around the Y axis, you'll see roughly this:

As you can see, the states flicker back and forth as the random walk plays out. Eventually the true state is far enough from the equator that the likelihood of overcoming the outward bias and returning to the equator is negligible. The true state gets pulled into a pole and, since the true state is dictating the measurement results and the measurement results control the random walk, the other states get pulled along with it.

It's possible to create 2-qubit cases where Eve's inferrence process won't converge like this one does, but before we talk about that we should talk about density matrices.

Density Matrices and Inefficiency

The inferrence-by-state-listing process I described above is simple, but horrendously inefficient. We're listing absurdly many states to get good coverage of the state space... and yet all the states end in the same place. There's obvious room for improvement.

A much better way to track what you know about a quantum state is the humble density matrix.

I won't be explaining how density matrices work in this post. Suffice it to say that, given a probability distribution of possible quantum states, you can compute a corresponding density matrix. And that it's easy to apply operations and measurements and post-selections to density matrices. And that if two probability distributions of states have the same density matrix, then those two distributions are observationally indistinguishable.

Basically, instead of tracking who-knows-how-many states, we're going to be applying operations to a single $2^n \times 2^n$ matrix. This is not only more efficient, it allows us to use standard methods for computing how much uncertainty is left in the inferrence process (via the Von Neumann entropy) and for comparing our inferred state to the true state (via the trace distance).

Of course, operating on a $2^n \times 2^n$ matrix is kind of expensive. This updated inferrence algorithm is better, but still hopelessly intractable before the number of qubits $n$ gets anywhere near 100. The algorithm will work in small cases, but for large cases it's merely a demonstration that security-against-eventual-cloning is based on a computational hardness assumption instead of being unconditionally secure.

I tried to prove that the hardness assumption we're making is strong, but didn't manage to do so. Making an inferred copy smells NP-Hard to me, but every time I try to make a reduction from 3-SAT or whatever I find that I forced Alice to find the solution instead of forcing Eve to find the solution. (Note: Eve's task is trivial if she has a PostBQP machine. But those don't exist in reality.)

Simulating More Qubits Being Inferred

To show that the density matrix solution can actually work, I implemented it. You can find the code on github in the Eve-Quantum-Clone-Computer repository.

For the example inferrence animated below, I tried to pick some interesting operations to apply. First, I had Alice constantly generate entropy that can't be predicted by Eve. That's done by constantly putting the first qubit into the state $\ket{0} + \ket{1}$ and measuring it. Also, Alice mixes in some extra entropy she generated herself. Second, I made the second qubit only affect measurements indirectly via its effects on the third qubit (which itself only indirectly affects the fourth qubit).

Here's the actual Alice code I used:

import Matrix from "src/math/Matrix.js"

import EveQuantumComputer from "src/EveQuantumComputer.js"

let numQubits = 4;

let qpu = EveQuantumComputer.withRandomInitialState(numQubits);

// Pre-compute matrices for operations.

let X0 = qpu.expandOperation(Matrix.PAULI_X, 0); // X gate on qubit 0.

let X3 = qpu.expandOperation(Matrix.PAULI_X, 3);

let H0 = qpu.expandOperation(Matrix.HADAMARD, 0);

let CNOT_2_ONTO_3 = qpu.expandOperation(Matrix.PAULI_X, 3, [2]);

let SMALL_Y_ROT_1 = qpu.expandOperation(

Matrix.fromAngleAxisPhaseRotation(Math.PI/3, [0, 1, 0]),

1);

let SMALL_X_ROT_2_WHEN_1 = qpu.expandOperation(

Matrix.fromAngleAxisPhaseRotation(Math.PI/4, [1, 0, 0]),

2,

[1]);

let CONFOUNDING_X3 = qpu.expandOperation(

Matrix.fromAngleAxisPhaseRotation(Math.PI/2 + 0.4, [1, 0, 0]),

3);

qpu.drawLoop(() => {

let generatedEntropy = qpu.measureQubit(0);

if (Math.random() < 0.3) { // Alice adding in her own home-grown entropy.

generatedEntropy = !generatedEntropy;

}

if (generatedEntropy) {

qpu.applyOperation(SMALL_Y_ROT_1);

qpu.applyOperation(X0);

}

qpu.applyOperation(H0); // Ensure next measurement of qubit 0 is 100% noise.

qpu.applyOperation(SMALL_X_ROT_2_WHEN_1); // 2 is affected by 1.

qpu.applyOperation(CNOT_2_ONTO_3); // And 3 is affected by 2.

qpu.applyOperation(CONFOUNDING_X3); // But the dependence is hidden by noise.

let measureResult = qpu.measureQubit(3);

if (measureResult) {

qpu.applyOperation(X3); // Clear.

}

});

And here's how the inferrence process played out:

As you can see, Eve eventually managed to infer a pretty good copy of Alice's state despite my attempts to make things difficult.

You can test out your own cases by cloning the repository and editing src/main.js.

The Uncloneable

At this point I think I've definitively established that sometimes Eve can infer the state of Alice's system and thereby create a clone. I mean, I literally provided working code. But there are also situations where Eve can't infer Alice's whole state.

First, there may be details of the state that don't affect any measurements. Remember how, in the two-qubit case we analyzed, the step size of the random walk degenerated to 0 when the toggly-ness of $U$ hit 50%? Setting the toggly-ness to 50% results in Eve never learning anything about the qubit $q_1$, because $q_1$'s state no longer influences any measurement results.

If Eve's ultimate goal is to predict Alice's measurement probabilities, then not learning details that don't affect those probabilities is fine. But even so, it's quite hard for Eve to figure out if she has all the relevant details or not. Determining if an Alice program will ever use a specific qubit is as hard as the halting problem; incomputable.

Second, if Eve's quantum computer can communicate with other quantum computers, Alice may ask Eve to entangle her state with external states. This is a problem for Eve because, although it's possible to clone an EPR pair as a whole, it's not possible to clone half of an EPR pair. That's literally non-sensical: you're asking for a qubit that agrees with $a$, but not with $b$ (otherwise you'd have a GHZ state instead of a clone), despite $b$ agreeing with $a$.

Alice may include external entanglement in the initial state, but that's not a problem. Eve's inferrence process handles that. The problem is if Alice can add new entanglement: it's the only way she can consistently add entropy into Eve's inferred density matrix.

Third, there's the pragmatic issue of size. For $n$ qubits and $m$ operations, Eve's inferrence algorithm does $O(4^n m)$ work. So an easy way for Alice to defeat a naive Eve is to just concatenate 100 qubits onto the state.

On the other hand, in practice, Eve won't be so naive. She'll be looking for opportunities to ignore some of the qubits, or to measure them early, or to factor the state into independent sub-parts. There are a lot of ways that Alice could accidentally make things very easy for Eve.

On Brains

What does this all mean for inferring the state of quantum information in a brain?

It means that not all possible quantum brain architectures are clone-resistant. Quantum-ness is necessary for clone-resistance, but not sufficient. By loading the brain into Eve's quantum clone computer and simulating its normal operation, we might learn all of the hidden details.

The inferrence process won't work if the brain is intermittently refreshing external entanglement. And unused details will make it hard to tell if we've finished or not. And long-lived qubits with exponentially-small effects on measurements can add quite a lot of time to the process. And we're totally hosed in practice if we can't factor the problem into 30-qubit sub-systems. But still. The security is not unconditional.

Notes

Shouldn't measuring non-commuting observables, which has random unpredictable results, degrade Eve's estimate?

(For example, keep setting a qubit to $\ket{0} + \ket{1}$ and measuring it to build up unknown-to-Eve information.)

No. Entropy does get added into the state by the measurement, but it's immediately revealed by the measurement result.

The 4-qubit simulation above actually does this. It doesn't hurt the inference process at all. Eve can lose ground when unlikely measurements keep happening, biasing the inferrence towards a wrong answer, but the overall tendency is to gain ground.

The only way to consistently add entropy into Eve's inferred density matrix is to introduce external entanglement.

What about ancilla qubits that don't get measured (e.g. as in the Deutch-Josza algorithm)?

The final values of ancilla bits usually doesn't matter, or is implied by the measurements that are performed. That's why, after the algorithm is over, you just let them decohere (i.e. they get measured but you don't bother recording the result).

Feel free to try this case out! For example, the typical example Deutch-Josza circuit has an unnecessary ancilla. Does Eve manage to infer it when Alice runs that circuit?

Doesn't this violate the no-cloning theorem?

No. We're not cloning an unknown state, we're producing a known state. What's interesting is how we came to know that state.

In practice wouldn't measurement error and other intrinsic sources of noise be a problem?

Maybe. It might also be a resource. For example, all the states reachable by plausible noise could count as copies for our purposes.

The inferrence process is absurdly intractable.

Yup. Still, the existence of a computable inferrence process downgrades security from unconditional to computational-hardness-assumption.

Summary

If you tell someone everything you're doing to your secret quantum state, and what measurement results you're getting, it gradually stops being a secret.

A quantum computer knows everything you're asking it to do to your secret quantum state, and what measurement results you're getting.

In principle, in some cases, a heedful quantum computer can gradually infer what state it's operating on.

Putting quantum information into a brain is necessary, but not sufficient, for unconditional security against cloning.