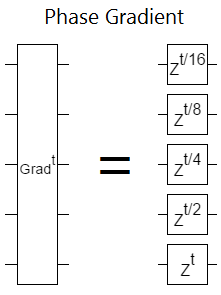

The phase gradient is a useful, but under-appreciated, quantum operation. When you apply a phase gradient to a register, each computational basis state $|k\rangle$ is phased by an amount proportional to $k$:

$$\text{Grad}^t = \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} |k\rangle \langle k| \exp(i \tau t k / N)$$

Phase gradients are the frequency-space equivalent of incrementing a register, but a lot cheaper. The reason it's so cheap is that a phase gradient doesn't have to do any multi-qubit interactions. Phase gradients factor into separate Z rotations on each qubit:

Shown above: a phase gradient can be done in constant depth (assuming you don't have to decompose the single-qubit rotations).

In fact, in near-term hardware, uncontrolled rotations around the Z axis are even cheaper than they look. Assuming your hardware is able to rotate around any axis in the XY plane, and that the only two-qubit operation your hardware supports is a CZ, and that you aren't bothering with error-correction, then you never need to literally rotate a qubit around the Z axis. Instead, you can implement Z rotations at compile time by appropriately phasing all future operations. So an uncontrolled phase gradient isn't just constant depth, it's zero depth (... with a bunch of caveats).

Phase Functions

Although the effect of a phase gradient is quite simple, it's a key part of implementing more complicated effects. For example, suppose I ask you to phase each state $|k\rangle$ by an amount proportional to some function $f$ of $k$, like $k^2$ or $\ln k$. How would you go about doing that?

Initially this task seems daunting. When I tried to solve it, the first idea I came up with was to pick a value of $k$, classically compute $f(k)$ so I knew how much to phase the $|k\rangle$ state by, use a whole bunch of controls to ensure I was only affecting that one state, apply the phase, then repeat again and again for all $2^N$ values of $k$. Of course, that's horrendously exponentially inefficient.

But, if you can compute a binary approximation of $f$ efficiently, there's a better way. Because if you have a register storing $f(k)$, hitting that register with a phase gradient will phase by an amount proportional to $f(k)$. So just do that: reversibly compute an approximation of $f$ into some register, hit that register with a phase gradient, then uncompute $f$.

This "compute-gradient-uncompute" trick is very general, but for specific cases there are often more efficient techniques.

Phasing in the QFT

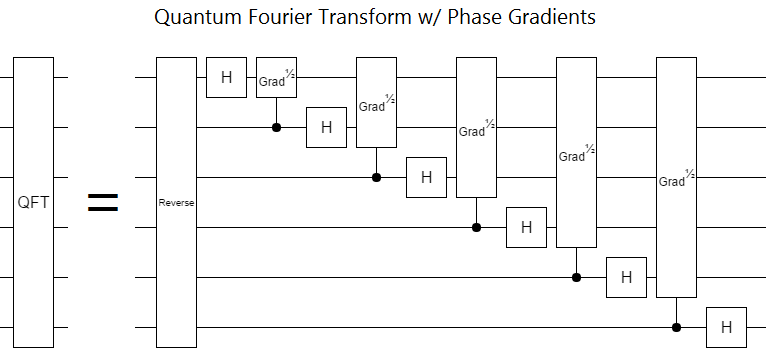

The quantum fourier transform uses phase gradients:

Notice that the phase gradients in the QFT are controlled. This is a problem; it ruins our constant-depth property! The control qubit can only control one operation at a time, so we can't apply the underlying Z rotations all at once.

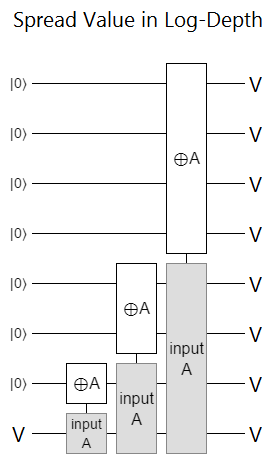

We could treat this controlled phase gradient as a function $f(k, c) = k \cdot c$ to phase by, but adding $n$ extra qubits just to store $k \cdot c$ is pretty excessive. If we had $n$ extra qubits available, they'd be better used by as temporary copies of $c$; redundant controls that can be applied in parallel. You can spread a single bit over a whole register in logarithmic depth, so this would be quite efficient:

Still, in order to be able to apply all the controls in parallel we would still need those $n$ extra qubits, and qubits are expensive. If we double the number of qubits required to perform an operation (i.e. needed $n$ extra qubits to perform a QFT), and we wildy speculate that quantum computers will gain capacity in a Moore's-law-esque fashion, then we just added an extra year to how long we have to wait before a problem fits onto an available quantum computer.

What we want is an efficient way to do controlled phase gradients inline, without any extra qubits.

Reverse Control

A pretty good trick to keep in mind when trying to control an operation is: "Can I reverse the effect of this operation by adding simple stuff around it?". For example, if you apply a modular multiplicative-inverse operation before and after a multiplication operation, the operation will divide instead of multiplying. Another example: pre and post NOT-ing all the target qubits of a subtraction will invert the subtraction into an addition.

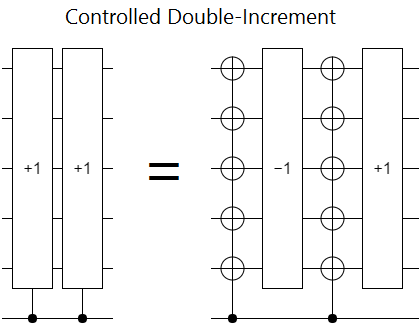

If you have some simple way of reversing an operation by surrounding it with stuff, then controlling the stuff around the operation will actually be controlling whether the operation goes forwards or backwards. Surround a decrement operation with NOT gates controlled by a qubit $c$, and what you've implemented is the operation "if $c$ then increment, else decrement". Then, by adding an extra increment, you get the operation "if $c$ then increment twice".

As long as controlling the stuff around the operation is easier than controlling the operation itself, this control-by-reversing trick should save space and (maybe) time. The main problem, which you can see on the left-hand side of the above diagram, is that you end up applying the operation you wanted to control twice instead of once. So really you need to start with a square root of your intended operation, and apply the reverse-control trick to that.

The way you go about creating a square root for an operation will change from situation to situation. In the case of incrementing, there's an easy trick: add an extra qubit at the low end of the register. Then you have to increment twice in order to increment the all-but-low-bit part of the register once. Only one of the increments will carry into the qubits you care about, the extra qubit you used doesn't need to be in any particular state, and you won't mess up that state.

By contrast, finding modular square roots is hard. So multiplication isn't so easy to control with this trick. That being said, all the multiplications you do in, say, Shor's algorithm are sourced from a random number $x$ that you chose at the start. If you instead pick a random $y$ and derive $x = y^2 \pmod{R}$ from it, then you'll always know a workable square root (and the overall algorithm works just as well).

Lucky for us, the operation we care about in this post, the phase gradient, is easy to square root. Just rotate each qubit by half as much. It's even easy to reverse the direction of the gradient! When you apply a NOT gate to all the qubits in a register, the register transitions from storing $k$ to storing $~k = -k-1 \pmod{2^N} = -k + 2^N-1$. So the phase gradient will phase by $-k + 2^N-1$, which decreases with $k$ instead of increasing with $k$.

Notice that the inverted-phase-gradient phase is not quite right. It's $-k + 2^N-1$ instead of by $-k$. We're off by $2^N-1$ Normally this wouldn't matter; $2^N-1$ doesn't depend on $k$ and so it would be an unobservable global phase factor. But, because we are performing a controlled operation, that "global" phase will only apply locally; in the part of the superposition where the control is satisfied. We have to apply fixup operations on the control to counter this effect.

(Side note: ironically, when there's more than one control, the fixup operation is a controlled-Z rotation. And the way to implement Z rotations with many controls... is with phase gradients!)

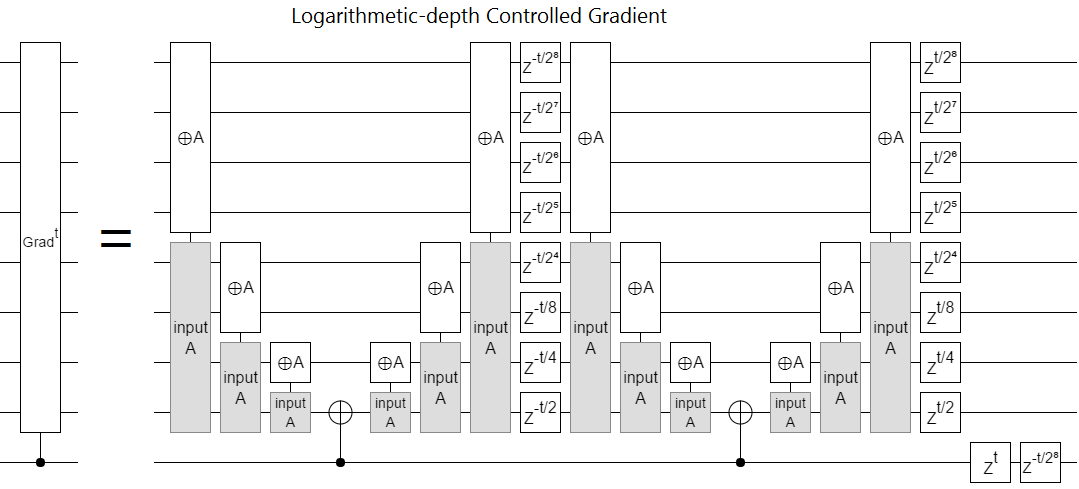

Putting all that stuff I just said together gives us this construction:

We use the control to seed a toggle that spreads over the target register in logarithmic depth. Then we apply an unconditional square-rooted-and-reversed phase gradient (for free!), undo the toggle, and then a squared-rooted forward-phase-gradient (for free!). We finish with a Z rotation on the control that corrects the $-t \cdot (2^N-1)$ phase offset between the control-off and control-on cases.

When the control isn't satisfied, the toggles don't happen and the two opposing phase gradients undo each other. When the control is satisfied, the first phase gradient is inverted so that it adds together with the other phase gradient into the operation we want. This process introduces some extra phase that doesn't depend on $k$, and the the Z rotations on the control cancel that extra phase. All in all, we managed to apply the controlled phase gradient in $\lg n$ depth.

This controlled phase gradient construction immediately improves the depth of the naive QFT construction I showed earlier from $O(n^2)$ to $O(n \lg n)$. Actually, since in practice we don't have to bother with Z-rotations below some error threshold, the depth is more like $O(n \lg \lg \frac{1}{\epsilon})$. This isn't anything revolutionary, there are far better QFT constructions, but it's still a nice simple inline improvement.

Summary

When trying to control an operation in a way that scales, without using workspace, look for pre/post operations that make the target operation do the opposite thing and a way to cut the operation's effect in half.

A controlled $n$-bit phase gradient can be performed in $O(\lg n)$ depth with $O(n)$ gates.