Recently, I was trying to learn more about the surface code by reading through the 2012 paper "Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation" by Austin Fowler et al. The paper is great; it uses lots of concepts and ways of thinking about quantum states that I'm not used to. However, there was one notable exception to that pattern: the S gate construction.

In Fowler et al's paper, the "native" operations available to the surface code are CNOT, H, X, Y, and Z. There is a significant difference between the Pauli gates (X, Y, and Z) and the H and CNOT gates. Namely, the Pauli gates can be performed within the control software, without actually doing anything extra to the qubits. The Pauli gates don't use up any "volume"; they're effectively free. This difference in cost will be important.

Non-native gates are performed with combinations of the native gates, often aided by specially prepared ancilla states. For example, in order to perform the S gate, Austin et al. keep re-using the ancilla state $|Y\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}|0\rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} i |1\rangle$.

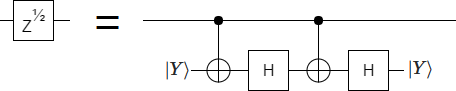

I've thought about this kind of gate-from-re-usable-ancilla construction in the past. In fact, I came up with the exact same S-gate-via-ancilla circuit as the one used in the paper:

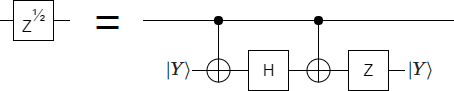

As soon as I saw the above circuit in the context of the paper, i.e. knowing that Pauli gates are cheaper than CNOT or H gates, I had to try optimizing it in Quirk. And it worked! It turns out that the outside Hadamard gate is simply fixing a phase flip of the ancilla state; you can use a Z gate instead:

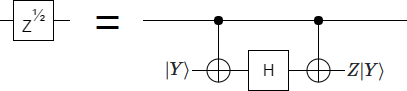

Actually, within the context of the surface code, Pauli gates are so cheap that it feels misleading to draw a whole box with a Z inside it. A more cost-representative way to draw the circuit is like this:

Note that this is basically the same circuit that we started with, but with the outside Hadamard removed. It's not very often that you make a circuit better by simply dropping an operation! (Sorta.)

Austin Fowler is one of my co-workers, so I sent him an email noting this silly little optimization. It would be unfair to say that Austin was excited, but anything that makes the surface code even slightly closer to practical tends to make his day. So that was good.

Austin and I also happen to be fans of the idea of publishing these little discoveries by themselves. Globbing something like this into the background of a larger paper just makes it harder to find. Sure it won't meet the significance criteria of a journal, but it's still worth putting out there.

So, with that in mind, I set out to write the shortest paper I possibly could. It had an abstract, the abstract said to look at figure 1, and figure 1 was the old circuit followed by the new circuit. Also there was a reference. It took all of half of a page.

Austin didn't find the extreme brevity as funny as I did, unfortunately. He fleshed out the paper with some justification, a more appropriate set of references, and some follow-up diagrams. The result is now on the arXiv as: "A slightly smaller surface code S gate".