In this post: extending pebble games to include measurement based uncomputation.

A pebble game is a simplified abstraction of a reversible computation. A pebble game is played on a directed acyclic graph. Every node of the graph represents some intermediate value that can be computed and uncomputed. At any given time the value is either computed (in which case the node has a pebble) or not (in which case the node is empty). Introducing a pebble onto a node corresponds to computing its intermediate value. Removing the pebble corresponds to uncomputing that value. If all of a node's incoming neighbors have a pebble, you can toggle whether or not that node has a pebble. The goal is to go from the initial state (no pebbles) to the state where the output node(s) have a pebble, while minimizing operations (number of times you add/remove a pebble), space (maximum number of pebbles simultaneously present), etc.

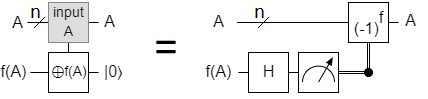

Quantum computations can often be modelled as pebble games, because maintaining coherence typically requires reversibility. A notable exception to this rule of thumb is measurement based uncomputation. The goal of an uncomputation is to reduce the redundant state $\sum_k \alpha_k |k,f(k)\rangle$ to the compressed state $\sum_k \alpha_k |k\rangle$. A measurement based uncomputation is a probabilistic method for performing this operation. It starts by measuring the redundant qubit $q=|f(k)\rangle$ in the X basis and discarding $q$. If the measurement result was False (meaning $|+\rangle$), then the uncomputation succeeded; the system returned to the desired state. If the measurement result was True (meaning $|-\rangle$), then the system ended up in the state $\sum_k \alpha_k |k\rangle (-1)^{f(k)}$ instead of the desired state (note the extra phase factor of $(-1)^{f(k)}$). In this case the uncomputation is finished by applying operations that cancel the unwanted phase:

(Note that it's usually trivial to take a method for computing $f$ and derive a slightly cheaper method to phase by $(-1)^{f}$. Sometimes there are non-trivial optimizations that make it significantly cheaper.)

Because the uncomputed qubit is a function of other qubits in the computational basis, measuring it in the X basis will generate one bit of entropy. The measurement has a 50/50 random result. This means that, when uncomputing a single qubit, half of the time you don't have to do anything and half of the time you do the work that's slightly easier than the work you'd have had to if uncomputing by exactly reversing the computation. (When uncomputing large multi-qubit registers, the benefit may be less because the chance of having to do nothing becomes exponentially small.)

Measurement Based Uncomputation in Pebble Games

In the context of a pebble game, there are two things that make measurement based uncomputation interesting. First, even if you can't currently compute or uncompute $f$, you can remove $f$'s output from memory by measuring the output in the X basis. You will eventually need to correct any resulting phase error, but that can be done at a later time. Second, there is a chance that just doing the X basis measurements is enough to uncompute $f$. Both of these facts have large consequences on the cost of uncomputation.

Before we go into examples of how measurement based uncomputation can save space and time in pebble games, we need to extend pebble games to include the concept. Basically we no longer require all of a pebble's dependencies to be present in order to remove the pebble. You can remove a pebble at any time. However, if a dependency is missing when you remove a pebble from a node, then there is a 50/50 chance that the node will now contain a ghost. A ghost can be removed from a node if all of its dependencies are present, and the pebbling task is not complete until all ghosts have been removed from the graph. I'll refer to pebble games that allow uncomputation ghosts as spooky pebble games.

Let $S(G)$ be the space required to pebble the graph $G$. That is to say, $S(G)$ is the maximum number of pebbles that will be simultaneously present when pebbling across the graph $G$ using an optimal strategy. Let $T(G)$ be the time required to pebble $G$. That is to say, $T(G)$ is the total number of steps (adding a pebble, ghosting a pebble, or removing a pebble/ghost) used when pebbling across the graph $G$ using an optimal strategy.

Consider the line graph $L_n$ of $n$ nodes arranged into a directed path. Our goal is to reach the state where there is a pebble on the node at the end of path, and no pebbles or ghosts anywhere else in the graph. I will now show how having access to ghosts makes this task less expensive.

Saving space when pebbling the line graph

In a normal pebble game, $S(L_n)$ is at least $\Omega(\lg n)$. The number of pebbles needed to travel across the line graph grows as the length of the line grows. (Exercise for the reader: prove it.) An example of a strategy that pebbles $L_n$ using $\Theta(\lg n)$ space is the following divide and conquer approach. Recurse on the first half to place a pebble at position $n/2$, then recurse on the second half to place a pebble at position $n$, then recurse on the first half to remove the pebble at position $n/2$. This simple strategy has a time complexity of $T(n) = 3T(n/2) = \Theta(n^{\log_2 3}) \approx \Theta(n^{1.58})$.

function normalDivideAndConquer(offset, length, action=ADD_PEBBLE) {

// Base cases.

if (length === 0) {

return;

}

if (length === 1) {

act(action, offset);

return;

}

let h = (length+1) >> 1;

// Recursively place pebble at midpoint.

normalDivideAndConquer(offset, h, ADD_PEBBLE);

// Recursively place pebble at endpoint from midpoint.

normalDivideAndConquer(offset + h, length - h, action);

// Recursively clear midpoint.

normalDivideAndConquer(offset, h, CLEAR_PEBBLE);

}

In a spooky pebble game, the space doesn't have to grow with $n$. In fact, $S(L_n) = 3$. The strategy that achieves this is quite simple: you can slide a pebble across the graph by adding a pebble in front of the current position $k$ and then ghosting the pebble at $k$. This allows you to get the required pebble to position $n$ using only two pebbles, but leaves behind ghosts at potentially all positions less than $n$. You remove the ghosts by iteratively sliding a pebble up to the point just before the furthest ghost, using the pebble to remove the ghost, then ghosting the pebble. Repeat until complete.

function constantSpace(length) {

let remaining = length;

while (remaining > 0) {

// Slide pebble to just before the furthest space that needs to be modified.

for (let i = 0; i < remaining - 1; i++) {

act(ADD_PEBBLE, i);

if (i > 0) {

act(GHOST, i-1);

}

}

// Fix furthest space.

act(remaining === length ? ADD_PEBBLE : CLEAR_PEBBLE, remaining - 1);

remaining -= 1;

// Ghost earlier pebble and find next space that needs to be fixed.

if (remaining > 0) {

act(GHOST, remaining - 1);

}

while (remaining > 0 && state[remaining - 1] === 0) {

remaining -= 1;

}

}

}

This solves the graph using three pebbles (one to leave at position $n$, one to slide across the graph, and one to assist with the sliding). The time complexity is quadratic, which is not very good, but the space complexity is amazing.

Saving time when pebbling the line graph

The divide and conquer strategy used to solve the normal pebble game in minimal space can have its time complexity lowered by using ghosts. Instead of always recursing to remove the middle pebble, we ghost it and then recurse only if necessary (meaning the third recursive call is needed half as often).

function divideGhostAndConquer(offset, length, action=ADD_PEBBLE) {

// Base cases.

if (length == 0) {

return;

}

if (length == 1) {

act(action, offset);

return;

}

let h = (length+1) >> 1;

// Recursively place pebble at midpoint.

divideGhostAndConquer(offset, h, ADD_PEBBLE);

// Recursively place pebble at endpoint from midpoint.

divideGhostAndConquer(offset + h, length - h, action);

// Ghost the midpoint.

if (act(GHOST, offset + h - 1)) {

// Recursively clean up ghost only if needed.

divideGhostAndConquer(offset, h, CLEAR_PEBBLE);

}

}

Ghosting the midpoint pebble reduces the expected time complexity from $\approx \Theta(n^{1.58})$ to $T(n) = 2.5 T(n/2) = \Theta(n^{\log_2 2.5}) \approx \Theta(n^{1.32})$. Note that the time complexity improved asymptotically, even though we didn't really do anything particularly different. We didn't even use additional workspace. (Often we use slightly less!)

We can improve the time even more by noticing that a ghost produced during the first recursive call doesn't have to be cleaned up right away. It can be cleaned up during the third recursive call. This suggests a strategy where we always perform the third recursive call but, during the first recursive call, we set a flag that says "don't bother cleaning up ghosts". In effect, this is a new strategy where we slide a single pebble across half of the graph, recurse on the second half, then recursively clean up the first half.

function sweepAndClean(offset, length, action=ADD_PEBBLE) {

// Base cases.

if (length === 0) {

return;

}

if (length === 1) {

act(action, offset);

return;

}

if (length === 2) {

act(ADD_PEBBLE, offset);

act(action, offset + 1);

act(CLEAR_PEBBLE, offset);

return;

}

// Slide pebble to mid point.

let h = (length + 1) >> 1;

for (let i = 0; i < h; i++) {

act(ADD_PEBBLE, offset+i);

if (i > 0) {

act(GHOST, offset+i-1);

}

}

// Recursively solve second half.

sweepAndClean(offset+h, length-h, action);

// Ghost the midpoint pebble.

act(GHOST, offset+h-1);

// Recursively clean up the first half.

while (h > 0 && state[offset+h-1] === 0) {

h -= 1;

}

sweepAndClean(offset, h, CLEAR_PEBBLE);

}

This gives the much better time complexity of $T(n) = \Theta(n) + 2 T(n/2) = \Theta(n \lg n)$, while still using $\lg n$ space.

I could give lots more examples (e.g. involving linear time strategies for $L_n$, or involving other graphs), but I hope these simple ones get the point across. Having access to measurement based uncomputation can result not just in constant factor time savings when uncomputing, but in asymptotic space and time savings when both computing and uncomputing.

Spooky challenges for the reader:

- Pebble $L_n$ in less than quadratic time using a constant number of pebbles.

- Pebble $L_n$ in linear time using less than $\Omega(\sqrt{n})$ space.

Summary

Spooky pebble games are pebble games augmented with the ability to model measurement based uncomputation. A measurement based uncomputation can remove any pebble at any time, but has some probability of leaving behind a ghost. Ghosts can't fulfill a dependency and have to be cleaned up, but don't take up space and can be removed in the same way that a pebble would be. Spooky pebble games often have more efficient solutions than normal pebble games, because they allow space to be reclaimed before an uncomputation starts instead of after it ends.

People often say that, in principle, quantum computation can be performed using zero energy because it is reversible and therefore bypasses the Landauer limit. But in the real world, where we can't get anywhere near the Laundauer limit, the way to minimize energy usage is to reduce operation count. Measurement based uncomputation intrinsically generates entropy (due to the X basis measurements), but it uses significantly fewer operations. So, ironically, we will optimize the energy usage of quantum computations not by staying pure to our reversible Landauer-less roots but instead by using an irreversible form of uncomputation that generates entropy.