Quantum teleportation is the inverse of superdense coding (which I talked about last week). Instead of consuming a previously shared qubit to encode two classical bits into a single quantum bit, quantum teleportation consumes a previously shared qubit to encode a desired qubit into two classical bits.

People often focus on the fact that teleportation can send qubits at all but, because you already need the ability to send qubits in order to set quantum teleportation up in the first place, that's not what makes it useful. Instead, its utility comes from the ability to "store" quantum bandwidth and thereby improve quantum channels in interesting ways.

In this post I'll go over the quantum teleportation process, and outline a few possible applications.

Quantum Teleportation

In case I can't explain things, here's a video explanation of quantum teleportation by someone else. You may have to watch the whole series of videos it's part of before things click, though.

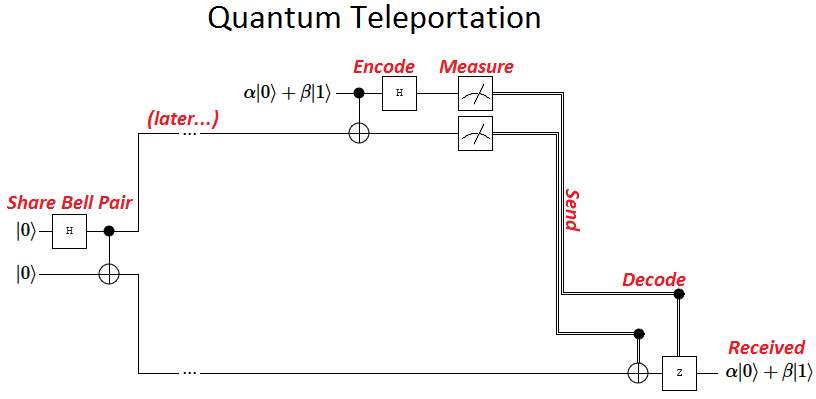

My circuit diagram for quantum teleportation is a lot like the one for superdense coding, except the encoding and decoding steps are swapped:

Like last time, the top of the diagram corresponds to "Alice", who wants to send a quantum bit to "Bob" (the bottom). Let's look at how the state of the system changes as time passes, and operations are applied, going from left to right.

Initially, the system is in the all-zero state. Alice hasn't initialized her qubit, and the bell pair hasn't been created yet. We represent this algebraically, using ket notation, as:

$\left| 0 \right>\left| 0 \right>\left| 0 \right> = \left| 000 \right>$

From this state we are going to create a bell pair, then have Alice encode her qubit, then decode it at Bob's.

Creating the Bell Pair

The first thing that must be done, before Alice can even consider teleporting a qubit to Bob, is the sharing of a bell pair. Two qubits must be placed into a superposition where they are either both true or both false. This is done by applying a Hadamard operation to one of the qubits, then applying a conditional not from that one to another.

The Hadamard operation (H) sends the state $\left| 0 \right>$ to the superposition $\left| 0 \right> + \left| 1 \right>$, and the state $\left| 1 \right>$ to the superposition $\left| 0 \right> - \left| 1 \right>$. Well, actually there's also a factor $\sqrt{2}$ in there but I'll be ignoring those throughout. We will use the second and third bits for our bell pair, so let's apply H to the second position. Its value is $\left| 0 \right>$, so it becomes $\left| 0 \right> + \left| 1 \right>$:

$\rightarrow \left| 0 \right>\left(\left| 0 \right> + \left| 1 \right>\right)\left| 0 \right> = \left| 000 \right> + \left| 010 \right>$

Notice how you can distribute the multiplication of kets across addition, which is useful for representing the state succinctly or in ways that are easy to operate on. Now we apply the conditional not, flipping the third bit in any parts of the superposition where the second bit is set:

$\rightarrow \left| 000 \right> + \left| 011 \right> = \left| 0 \right> \left(\left| 00 \right> + \left| 11 \right> \right)$

The bell pair has been created. Alice and Bob each get one of entangled qubits, and we move on to encoding.

Encoding

Alice needs a qubit to send, so suppose she has applied some operations that have put the first bit into some unknown superposition $\alpha \left| 0 \right> + \beta \left| 1 \right>$. After those operations the state of the entire system changes to:

$\rightarrow (\alpha \left| 0 \right> + \beta \left| 1 \right>) \left(\left| 00 \right> + \left| 11 \right> \right) = \alpha \left| 000 \right> + \alpha \left| 011 \right> + \beta \left| 100 \right> + \beta \left| 111 \right>$

To encode the qubit for teleportation, Alice conditionally not's it into her half of the bell pair. So we flip the second bit in the parts of the superposition where the first bit is set:

$\rightarrow \alpha \left| 000 \right> + \alpha \left| 011 \right> + \beta \left| 110 \right> + \beta \left| 101 \right>$

After the conditional not, Alice must apply the Hadamard operation to her qubit (bit #1). Keeping in mind the "0 to 0+1 and 1 to 0-1" rule, we find that the operation changes the state to:

$\rightarrow \alpha (\left| 000 \right> + \left| 100 \right>) + \alpha (\left| 011 \right> + \left| 111 \right>) + \beta (\left| 010 \right> - \left| 110 \right>) + \beta (\left| 001 \right> - \left| 101 \right>)$

$= \alpha \left| 000 \right> + \alpha \left| 100 \right> + \alpha \left| 011 \right> + \alpha \left| 111 \right> + \beta \left| 010 \right> - \beta \left| 110 \right> + \beta \left| 001 \right> - \beta \left| 101 \right>$

We're not going to worry about what measuring does to our state, because you can always delay measuring without changing the outcome. So the encoding is done, and we can move on to decoding.

Decoding

Bob decodes the sent qubit by applying operations based on the classical bits he receives. He conditionally nots the second bit into his half of the bell pair, and conditionally Z-rotates his half of the bell pair based on the first bit.

To do the conditional not we look at the superposition and flip the third bit wherever the second bit is set, resulting in this state:

$\rightarrow \alpha \left| 000 \right> + \alpha \left| 100 \right> + \alpha \left| 010 \right> + \alpha \left| 110 \right> + \beta \left| 011 \right> - \beta \left| 111 \right> + \beta \left| 001 \right> - \beta \left| 101 \right>$

Now we have to apply a Z gate, conditioned on the first bit, to the third bit. The Z gate negates the phase of $\left| 1 \right>$, so whenever the first and third bit are both set, we multiply by -1:

$\rightarrow \alpha \left| 000 \right> + \alpha \left| 100 \right> + \alpha \left| 010 \right> + \alpha \left| 110 \right> + \beta \left| 011 \right> + \beta \left| 111 \right> + \beta \left| 001 \right> + \beta \left| 101 \right>$

And suddenly, things start to factor again:

$= \alpha \left| 000 \right> + \beta \left| 001 \right> + \alpha \left| 100 \right> + \beta \left| 101 \right> + \alpha \left| 010 \right> + \beta \left| 011 \right> + \alpha \left| 110 \right> + \beta \left| 111 \right>$

$= (\left| 00 \right> + \left| 10 \right> + \left| 01 \right> + \left| 11 \right>) (\alpha \left| 0 \right> + \beta \left| 1 \right>)$

$= (\left| 0 \right> + \left| 1 \right>) (\left| 0 \right> + \left| 1 \right>) (\alpha \left| 0 \right> + \beta \left| 1 \right>)$

Notice that the expression for the third qubit matches what Alice wanted to send. Her qubit was teleported to Bob, using only a classical channel, thanks to the previously shared bell pair. If the sent qubit had been entangled with other qubits, that would have been maintained as well (just like a normal quantum channel does).

Applications

Warning: All of these applications are hypothetical. In particular, they all rely on being able to store qubits for long periods of time. We don't know a good way to do that, yet.

As I mentioned in the introduction, my conception of what makes quantum teleportation useful is its ability to improve quantum channels by storing quantum bandwidth.

For example, you can use quantum teleportation to increase the reliability of a quantum channel. Imagine you have a business that needs to send qubits to a bank, to verify quantum money you receive. Unfortunately, your ISP has been doing a terrible job maintaining the quantum channel (because screw you we've got a monopoly). On any given day the quantum channel might go down for hours at a time, probably during business hours instead of at night when you don't need it. Quantum teleportation allows you to use that available night time bandwidth to share bell pairs, then use those shared pairs to maintain quantum communication with the bank during a daytime outage (as long as the classical internet is still working).

You can also use quantum teleportation to reduce latency. Suppose you have the same business as before, but it's in the middle of nowhere. There is no fiber optic cable to send qubits over, just a classical satellite link. If you want to send qubits to the bank, or vice-versa, you literally have to ship them. In a crate. You have a quantum channel... but it has latency measured in days instead of seconds. Quantum teleportation lets you cut that latency down to the latency of your satellite link: just have the bank send a steady stream of entangled bell pair shipments, then use those to teleport qubits over the satellite link.

Even if you have a quick reliable quantum channel available, quantum teleportation allows you to supplement it. Have a truck drop bell pairs off every day, and use those for additional bandwidth. Need more quantum bandwidth? Send a bigger truck. At least until you max out your classical bandwidth.

The last application for quantum teleportation, that I can think of, is turning one way channels into two way channels. Suppose you need a quantum channel to your friend, to do a private database query or generate a shared private key or something, but neither of you can send qubits. However, you can both receive qubits from some third party. Quantum teleportation allows you to use bell pairs generated by the third party to create a proper quantum channel between you and your friend.

Put that all together and quantum teleportation lets you turn a high-latency quantum channel that only goes one way and experiences frequent outages into a two-way low-latency quantum channel that works even if there's an outage. As long as you have a classical channel with those properties. Not bad.

I'll note again that none of this is practical yet. But, as with superdense coding, I enjoy, for its own sake, the hypothetical image of trucks dropping off boxes of bandwidth.

Summary

Quantum teleportation turns pre-shared entangled qubits into the ability to send quantum information over a classical channel. It can be used to improve the reliability and latency of quantum channels, when a good classical channel is available.