Recently, I got sniped. The sniper? An exercise in Nielsen and Chuang's textbook:

I thought it was wasteful to use a quadratic number of gates, and decided to try to instead construct a $C^nNOT$ gate out of a linear number of Toffoli gates and single-qubit gates (still without using any ancilla bits).

It took me waaaay too long to solve this problem, because I knew too little to start with and because it's hard to search for solutions to sub-cases. For example, go try to find a website or paper describing how to make a reversible increment gate out of Toffoli gates when you have an ancilla bit that's in an unknown state. I had to settle for coming up with my own constructions, or for tweaking what I did manage to find (e.g. this excellent diagram of a VanRentergem adder from this paper).

Anyways, I eventually found a solution to the problem and now I'm going to explain said solution in three parts. In the first part, this post, we'll learn how to construct a $C^nNOT$ when you do have an ancilla bit. Part 2's goal is to use that ancilla bit again, but for constructing incrementing gates. Finally, part 3 (the only part requiring anything quantum) will be about bootstrapping an ancilla bit out of nothing.

Reversibility

Reversible circuits are interesting for several reasons.

First, reversible circuits bypass the Landauer limit, one of the lower bounds on the energy required to do computation. In principle, if you didn't have to spend energy pumping errors out, a reversible computation could be done for free (i.e. without consuming neg-entropy; without turning energy into waste heat) (on the other hand, we're more than six orders of magnitude away from the limit so this is more of a far-off-future-hypothetically-useful kind of practicality).

Second, reversible circuits are a source of tantalizing problems and unique questions, whose solutions are applicable to quantum computing (where all operations are reversible, modulo thermodynamics). For example, you can classify reversible gates into equivalence classes based on "how universal" they are. And, of course, not being allowed to use NAND, AND, NOR or OR gates makes the circuit construction problems trickier.

Despite the loss of "standard" universal logic gates, there are still universal gates for reversible computation. However, these gates always come with caveats on their universality. The Fredkin gate (a controlled swap) can be used for universal computation, but it preserves the number of ON bits. As a result, you tend to need a linear number of ancilla bits to do anything useful with just Fredkin gates.

In this post we'll be using the much more flexible Toffoli gate, but it also has caveats. In fact, no reversible gate can build all reversible operations.

Permutations and Parity

Every reversible operation must map inputs to distinct outputs, such that every output comes from exactly one input. More specifically, the operation must be equivalent to a permutation of the state space.

Permutations have a parity. If it takes an odd number of swaps to perform a permutation, it has odd parity. Conversely, taking an even number of swaps means the permutation has even parity. When you chain permutations (i.e. apply one reversible operation followed by another) the parity of the resulting overall net permutation is the sum of the two chained permutations' parities. Chaining two even permutations or two odd permutations results in an overall even permutation. Chaining one even and one odd permutation (in either order) results in an overall odd permutation.

Parities are useful surprisingly often, when you want to show that something is impossible. For example, it's an integral component of the proof that you can create unsolvable sliding puzzle configurations. In particular, notice that the rules for adding parities implies that you can't create an odd permutation by chaining even permutations. We're going to use that limitation to show that some reversible operations can't be built out of smaller ones.

Consider a NOT gate with many controls, enough to touch all the wires of a circuit. For example, suppose we have a 10-bit circuit and we want to toggle the last bit when the first nine are ON (i.e. we have a $C^9NOT$). The permutation corresponding to that $C^9NOT$ swaps the $1111111110$ state with the $1111111111$ state, but leaves all the other states untouched. Since it performs one swap, and that's an odd number, the $C^9NOT$ is an operation with odd parity (when applied to a 10 bit circuit).

Now consider any operation that doesn't touch all the wires of a circuit. There must be some bit $b$ that the operation doesn't depend on or affect. So, when we look at the swaps performed by this operation, any swap it performs when $b=0$ must be matched by an equivalent swap performed when $b=1$. In other words, having an unaffected bit doubles the number of swaps (because the swap has to happen once in the $b=0$ case, and once in the $b=1$ case). Therefore the number of state space swaps performed by this operation must be even, so the operation has even parity.

Since a controlled-not that affects every wire has odd parity, and any operation affecting fewer wires has even parity, and chaining even operations can't create an odd operation, it is impossible to reduce an all-wires-touched controlled-not operation into smaller operations.

(Exercise: does this problem go away when using trits instead of bits?)

The parity wall sounds like a huge problem, but it's more about lack of working space than anything else. As soon as the controlled-not doesn't affect every single bit, the argument stops working. Although chained permutations preserve the total number of swaps when working modulo 2, that's not true for other moduli. As soon as we have even one uninvolved bit, one ancilla, we can sidestep the parity limitations.

Ancilla Bits

Ancilla bits are extra bits, not involved in the logical operation being performed, that give circuit constructions "room to move". In addition to making constructions possible in the first place, ancilla bits can allow for simpler or more efficient constructions.

Ancilla bits come in several different flavors. Sometimes you know their initial value, and sometimes you don't. Sometimes you're required to restore that initial value, and sometimes you're not. Usually, ancilla bits are implicitly assumed to start off in the OFF or ON state and gate constructions must get them back to the that state before finishing (so later gates can re-use the ancilla bit). However, in this post I'll be explaining how to work with each of four flavors.

To avoid ambiguity and confusion, let's name and define our four types of ancilla bits now:

- Burnable Bits: Guaranteed to be OFF initially, but with no restrictions on state afterwards. Basically, burnable bits are (a small amount of) neg-entropy you can consume to perform some irreversible computation.

- Zeroed Bits: Guaranteed to be OFF initially, and you must ensure they're OFF when you're done. Zeroed bits are generally used exactly like burnable bits, except you uncompute effects before continuing. Circuits using zeroed bits tend to be a constant factor larger than circuits using burnable bits because of the uncomputation tax.

- Garbage Bits: Could be in any state initially, and you can add more garbage into the state (you don't have to restore the initial value). Garbage bits tend to be trickier to use than burnable or zeroed bits, because you need to base logic around toggle detection. Toggle detection typically involves repeating a self-undoing operation twice, conditioned on the potentially-toggled garbage bit. When no toggling occurs the operation either doesn't happen or happens twice (undoing itself). Circuits using garbage bits tend to be a constant factor larger than circuits using burnable bits, because of the toggle-detection tax.

- Borrowed Bits: Could be in any state beforehand, and must be restored to that same state afterwards. Borrowed bits have the downsides of both zeroed bits and garbage bits, and pay both of their boilerplate taxes. However, borrowed bits are much easier to find because you can borrow bits from yourself. Any operation that doesn't affect the entire circuit can use unaffected wires as de-facto borrowable bits.

With those four types of ancilla bits in mind, let's start constructing some large controlled nots. We've already discussed why the no-ancilla-bits case is impossible, but what about the single-ancilla-bit case?

Single Ancilla Bit

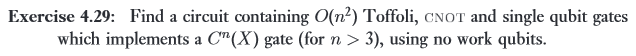

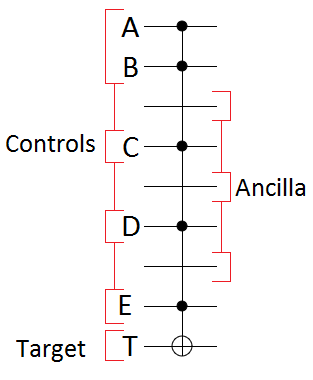

Given an $n+2$ wire circuit with $n$ control wires, one target wire, and one ancilla wire, we want to break a $C^{n}NOT$ into smaller operations. We want to take this:

and break it into controlled-NOTs with fewer controls. We don't need to get all the way down to 2 controls just yet, but we do need some way of reducing the maximum number of controls per operation.

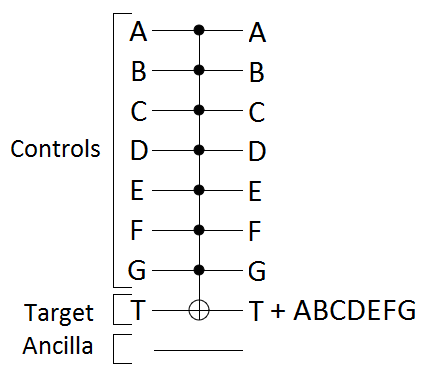

The easiest case is when our single ancilla bit is burnable. We can toggle the ancilla bit to be ON when half of the controls are ON, and then use a single control on the ancilla bit to play the role of that half of the controls:

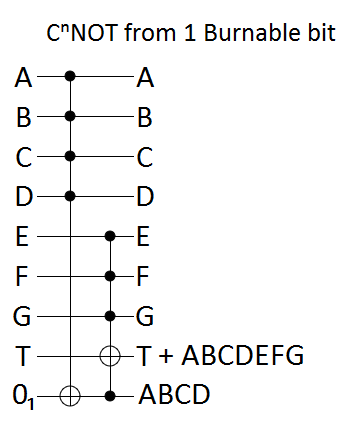

If our ancilla bit is a zeroed bit instead of a burnable bit, we need to uncompute the effects on it before finishing. Our effects happen to be very simple, and can be undone by simply repeating what we did to mess things up in the first place:

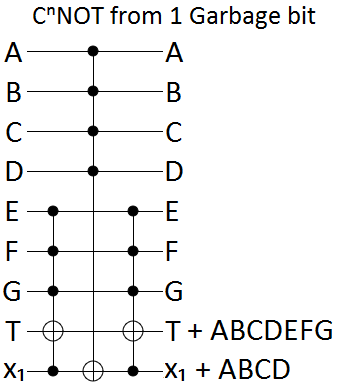

When the ancilla bit is a garbage bit, we do toggle-detection. We conditionally toggle T on both sides of the possible toggling of the ancilla bit, so that the T-toggling undoes itself unless the ancilla bit was toggled:

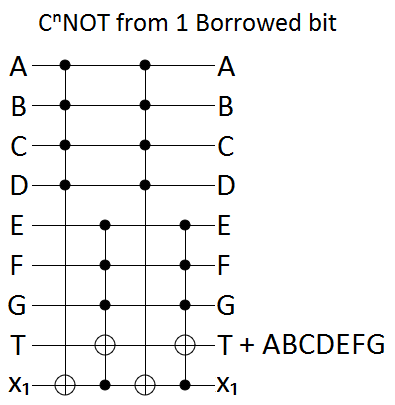

Finally, the borrowed bit case is just a combination of the garbage bit and zeroed bit tricks:

Each of the above constructions uses 1 ancilla bit to turn a $C^{n}NOT$ into a constant number of $C^{\frac{n}{2}}NOT$s (more specifically, we use $C^{\lceil \frac{n}{2} \rceil}NOT$s and $C^{\lceil \frac{n+1}{2} \rceil}NOT$s).

We could apply this construction iteratively, turning $C^{n}NOT$s into $C^{\frac{n}{2}}NOT$s into $C^{\frac{n}{4}}NOT$s and so forth $p$ times until we hit the base case of Toffoli gates when $\frac{n}{2^p} \approx 2$. Unfortunately, doing that would use more than a linear number of Toffoli gates.

For a borrowable bit, the recurrence relation resulting from iterating down to the base case would be $T(n) = 4 T(\frac{n}{2})$, which makes $T$ an $O(n^2)$ function.

Given a burnable bit, you might expect the recurrence relation to be $T(n) = 2 T(\frac{n}{2}) \in O(n)$... but really we can only burn the bit once, so we'd have to switch to treating it as a garbage bit after the first iteration.

For zeroed bits and garbage bits, things get more interesting. Naively, their recurrence relation should be just $T(n) = 3 T(\frac{n}{2}) \in O(n^{\lg 3}) \approx O(n^{1.585})$. However, we don't have to use an even split between the sizes of the sub-operations. Because only one of the sub-operations happens twice, we can gain efficiency by giving it proportionally fewer controls. Therefore we should instead be analyzing the recurrence relation $T(n) = 2 T(c_n \cdot n) + T((1-c_n) \cdot n)$, where $c_n$ is a parameter to be optimized that determines the asymmetry of the split. This is a very interesting recurrence relation that I unfortunately don't know how to solve. I can pick $c_n$s that will achieve $O(n^{1 + \epsilon})$ for arbitrarily small $\epsilon$, but I don't know if it's possible to reach $O(n)$.

Fortunately, we can sidestep the complicated recurrence relation issue. Notice that our single-bit constructions always create sub-operations which are quite a lot smaller. We're guaranteed to have at least $\lceil \frac{n}{2} \rceil$ unaffected bits available, and our operations will have size at most $C^{\lceil \frac{n+1}{2} \rceil}NOT$.

Oh, we can borrow all of those unaffected bits!

$n-2$ Ancilla Bits

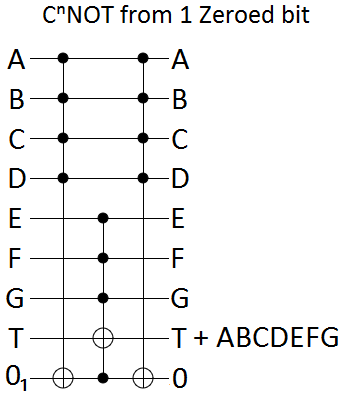

Given a $2n-1$ wire circuit with $n$ control wires, $n-2$ ancilla wires, and one target wire, we want to break a $C^{n}NOT$ into a linear number of Toffoli gates. We will intersperse the ancilla bits throughout the circuit, instead of putting them all at the bottom, to make the constructions look simpler:

Let's jump right in.

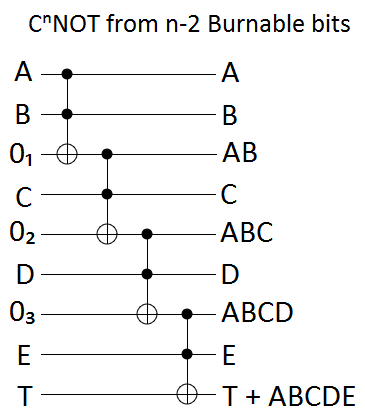

Once again, the burnable bits case is the simplest. We can use Toffoli gates to intersect controls together, and we can use the ancilla bits to store the gradually-accumulating intersection of all controls. In the end we'll have touched every burnable bit twice, and every control bit once:

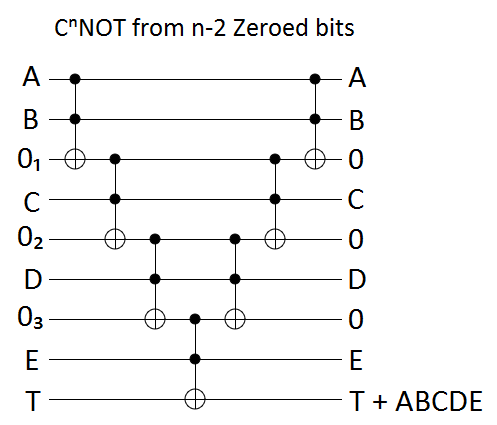

With zeroed bits, we have to uncompute the garbage we added into the ancilla bits. Uncomputing is just a matter of applying the same operations in reverse order, omitting only the operations that affected the target. This creates a circuit that looks like it's pointing towards the target:

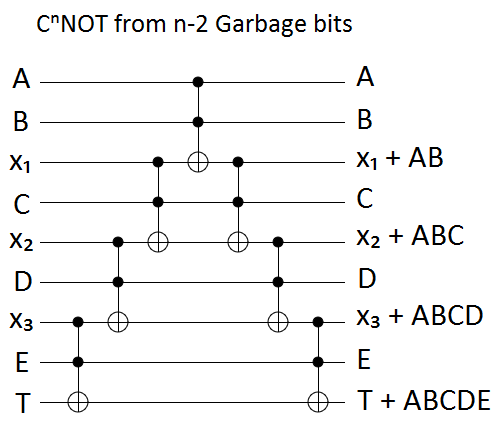

The garbage bit construction is again based on toggle detection, but this time we have to nest the construction. Nested toggle detectors will propagate toggling until one of them fails to fire, so we just keep nesting until we've conditionally toggled the target. The resulting circuit looks like an arrow pointing away from the target:

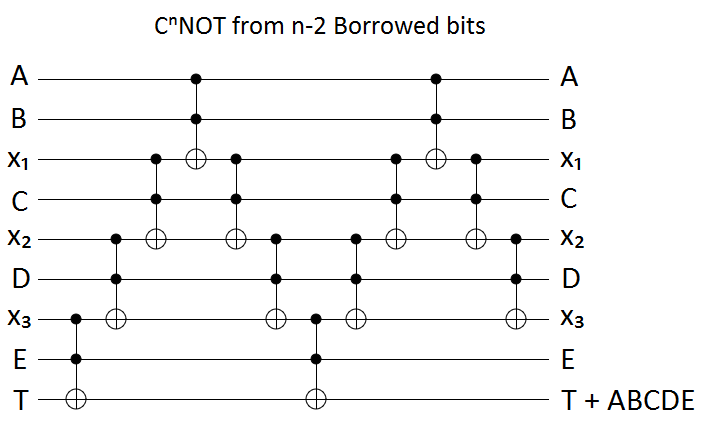

The borrowed bits solution again combines toggle-detection with uncomputation. We take the garbage bits solution, then uncompute the non-target-affecting operations:

Each of the above constructions uses $n-2$ ancilla bits to turn a $C^{n}NOT$ into $O(n)$ Toffoli gates.

Putting It All Together

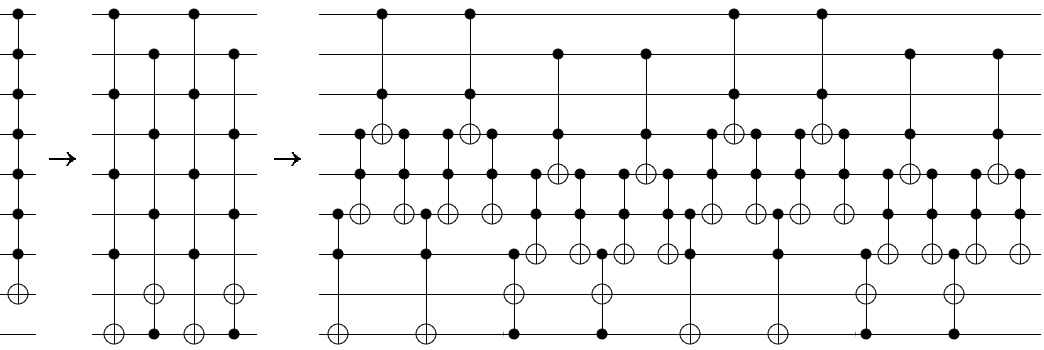

Our single ancilla bit construction was not efficient enough to be applied iteratively. Now that we have the efficient $n-2$ ancilla bit constructions, we can fix that efficiency problem by switching to the $n-2$ borrowed bit construction after applying the relevant single ancilla bit construction.

For example, here is the circuit resulting from using one borrowed bit to break a $C^7NOT$ into four $C^4NOT$s, then breaking each of those $C^4NOT$s into eight Toffoli gates by borrowing two unaffected bits:

This construction uses $\approx 16n$ Toffoli gates, achieving the $O(n)$ bound we were hoping for. This is asymptotically optimal, because without $\Omega(n)$ gates we'd be unable to include enough Toffoli gates to even touch all of the involved wires.

The constant factor on the number of needed gates depends on the type and number of ancilla bits we're given. Starting with a single burnable bit, instead of a borrowed bit, cuts the final number of Toffoli gates from $\approx 16n$ to $\approx 8n$. Starting with $n$ borrowable bits, instead of just one, is even better; achieving $\approx 4n$. Starting with $n$ zeroed bits or garbage bits, giving both a quality and quantity advantage, would get us down to $\approx 2n$. The best case scenario, $n$ burnable bits, requires only $\approx n$ gates.

Summary

With zero ancilla bits, it's impossible to build NOTs with lots of controls out of smaller operations. With just one ancilla bit, even if that bit is in an important unknown state that must be preserved, a NOT with $n$ controls can be built out of $\Theta(n)$ Toffoli gates. Having a larger quantity, or better quality, of ancilla bits improves the efficiency of the construction by constant factors.

Next time: the same thing, but with increment gates. Next next time: using quantum gates to bootstrap an ancilla bit.

Navigation

Part 1: (This Post)