This post is Part 2 of solving a quantum circuit construction exercise. In Part 1, Constructing Large Controlled Nots, we figured out how to reduce a NOT with many controls into a linear number of NOTs with two controls (i.e. Toffoli gates). However, we needed an ancilla bit to make the construction work.

In order to reach the end goal of constructing a NOT with many controls without an ancilla bit, we will need the ability to do large increments. That's what we'll be figuring out in this post: how to turn an $n$-bit increment gate into $O(n)$ Toffoli, CNOT, and NOT gates.

As with the controlled-not gate construction, we will need an ancilla bit to make the increment construction work (the permutation parity obstacle applies again). But we won't need to do anything quantum; everything in this post applies to your normal, everyday, classical, reversible circuits. (The quantum gates only show up next time, to bootstrap the ancilla bit.)

Incrementing

An increment gate is an operation that increases the two's-complement value represented by a group of wires.

For example, if a 3-bit increment gate is applied to a 3-bit circuit then the circuit's state will cycle from [Off, Off, Off] to [On, Off, Off] to [Off, On, Off] to [On, On, Off] to [Off, Off, On] to [On, Off, On] to [Off, On, On] to [On, On, On] and then back to [Off, Off, Off].

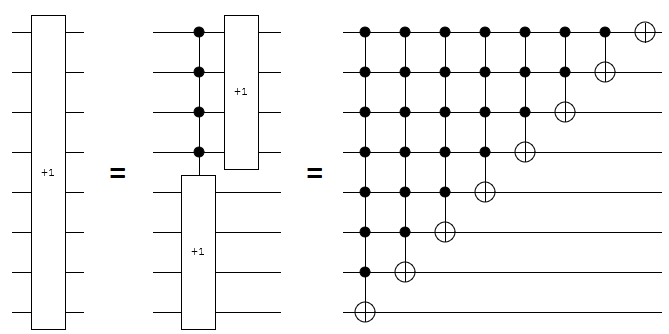

Implementing an increment gate out of NOT gates is easy, if you're allowed to have arbitrarily large numbers of controls.

The increment only propagates, as a carry, through the bits until it encounters an OFF bit.

Each bit flips if and only if all of the lower bits were ON before the incrementing started.

In other words, each wire gets a NOT that is controlled by all the preceding wires:

Our goal is to do the same thing that the above circuits do, but without using more than two controls on any NOT and without using more than $O(n)$ NOTs.

The most immediately obvious thing to try is to apply the large controlled-not construction from last time. Unfortunately, because that construction requires $O(n)$ gates per controlled NOT, we'd end up needing a quadratic number of gates in total (because $1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ... + n \in \Theta(n^2)$). We need to break the increment apart more intelligently than that.

Like last time, we'll solve the problem for various different types of ancilla bits. We'll consider burnable ancilla bits (initially zero, allowed to end up non-zero), zeroed ancilla bits (initially zero, must end up zero), and borrowed ancilla bits (unknown initial value, must end up as that same value).

(Side note: I'm skipping garbage ancilla bits (unknown initial value, allowed to end up different) this time because I didn't find a nice way for them to provide much benefit over borrowed bits.)

We'll start with the single ancilla bit cases.

Single Ancilla Bit

Given an $n+1$ wire circuit with $n$ increment wires and one ancilla wire, we want to break the increment into smaller operations. The goal, in this section, is not about getting all the way down to Toffoli gates. Instead, we simply want to reduce the size of the operations. Once the operations are small enough, possibilities open up because we can borrow bits not used by an operation as ancilla for that operation.

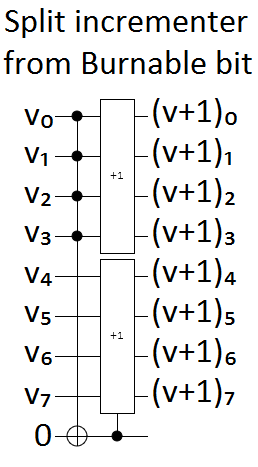

The first case to consider is what to do when the single given ancilla bit is burnable. The top wires, which store the low bits of the number we want to increment, can be incremented without depending on the bottom wires in any way. But the bottom wires, which store the high bits, should only be incremented when the top wires are all ON. We can avoid the bottom wires depending on $n/2$ top wires by storing the intersection of those wires in the ancilla bit. That way, the bottom increment only needs one control:

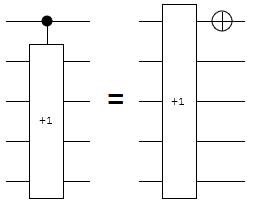

It's possible to absorb the single extra control into the increment gate. A controlled increment gate is equivalent to an increment gate with the control wire as the new lowest bit, except that the final NOT on the low bit is missing. So absorbing a control into an increment is just a matter of post-toggling the former control wire:

Note that it's important to treat the absorbed control bit as the low bit, even if the absorbed wire is in the "wrong" position. Either the control bit must be swapped into the right position, or a custom re-arranged increment gate will be needed.

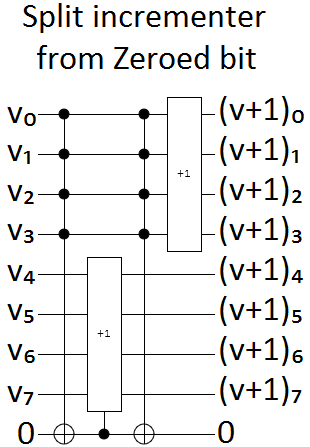

The next case to consider is the single zeroed bit case. All we need to do here is take our solution from the burnable bit case, and uncompute any effects on the ancilla bit. This is a simple addition to the circuit, because we only had one effect and it is easily reversed:

The last single-ancilla-bit case we're considering is the borrowed ancilla bit case. This time, it takes more than a simple tweak to make things work.

In the last post, we used toggle detection when working with garbage bits and borrowed bits. We repeated a self-undoing operation twice, conditioned on the ancilla bit, so that the operation would undo itself unless the bit was toggled. This won't work for incrementing, because the increment operation is not its own inverse.

I was stuck on this problem for awhile, but eventually realized that the trick was to use the bitwise complement. When the bits of a two's-complement number $X$ are all toggled, they switch from storing $X$ to storing $\overline{X} = -X-1 \pmod{2^n}$. If we increment the complemented value, then take the complement again, we end up with the result $\overline{\overline{X} + 1} = \overline{-X - 1 + 1} = -(-X)-1 = X-1$.

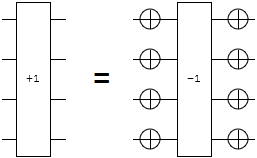

That means that surrounding an increment gate with NOTs turns it into a decrement! (And vice versa.)

The conversion from increment to decrement is useful to us because now we can now turn an increment into the inverse of an increment, and we can do it conditionally. That's the trick we'll use to make toggle detection work in this case:

- We will apply an increment gate and a decrement gate to the high bits of the number.

- Both operations will be conditioned on the borrowed ancilla bit.

- Whenever the low bits are all

On, we will toggle the ancilla bit, and the high bits, before and after the decrement gate.- If the low bits are not all

On, nothing will happen to the high bits. Either the borrowed ancilla bit will beOff, meaning neither the increment nor the decrement gate will take effect, or the borrowed ancilla bit will beOnand both the increment and the decrement gate will apply, undoing each other. In either case, the net effect is no effect. - If the low bits are all

On, then the NOTs around the decrement gate fire and transform the decrement into an increment. If the borrowed ancilla bit isOn, the increment gate will fire and the decrement-turned-increment gate will not. Otherwise the borrowed ancilla bit isOffand only the decrement-turned-increment gate will fire.

- If the low bits are not all

So, with the above plan, the high bits will be incremented exactly once when the low bits are all On, but nothing happens to the high bits if any of the low bits is Off.

That's exactly the logic we want for the high bits.

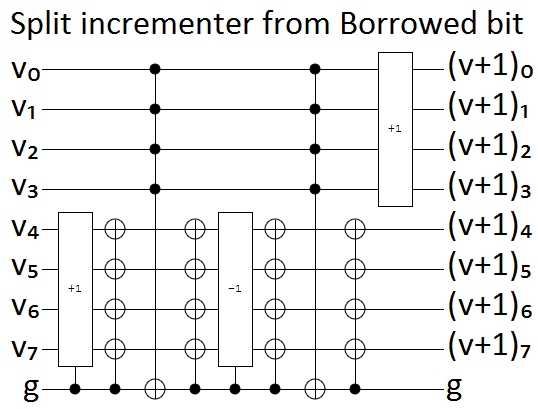

Here's what the single borrowed bit construction looks like, for 8-bit numbers:

The above circuit also uses one other trick, that I didn't mention.

Because we want to toggle so many bits when the first $n/2$ bits are ON, but we don't want to pay the quadratic price of having $n/2$ controlled-nots of size $n/2$, we use toggle-detection to spread the toggling of the ancilla bit to all of the target bits.

The single bit constructions we've covered let us turn any $n$-bit increment gate into two or three $n/2$-bit increment gates, depending on what type of ancilla bit we have. We could apply these constructions again and again, cutting the size of the remaining gates in half until we hit simple base cases, but that would not be asymptotically efficient.

(For example, the recurrence relation for iterating the single borrowed bit construction is $T(N) = 3 T(N/2) + O(N)$ and that means $T(n) \in O(n^{log_2(3)}) \approx O(n^{1.585})$, not $O(n)$. The recurrence relation for zeroed bits is $T(N) = 2 T(N/2) + O(N)$, which is better, but it still gives $T(N) \in O(n \log n)$ instead of $O(n)$.)

To achieve a linear number of gates, we'll need to borrow a lot more bits.

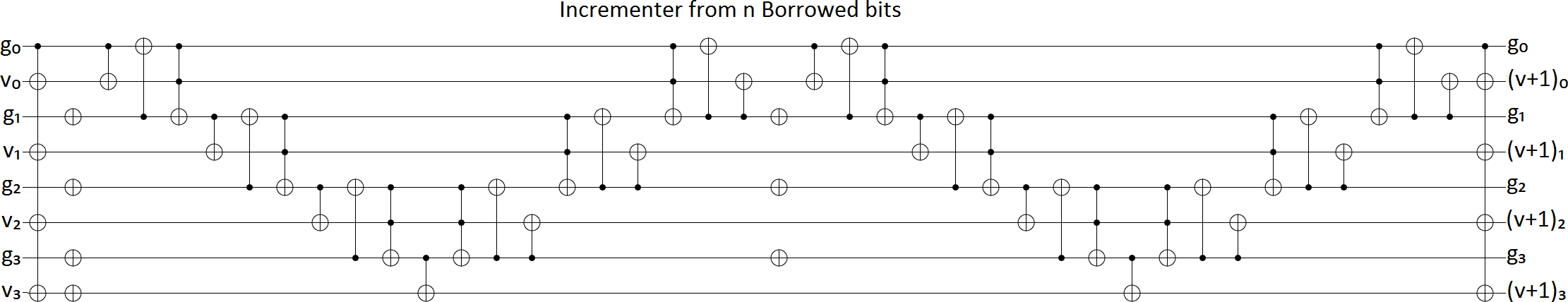

$n$ Ancilla Bits

Given a $2n$ wire circuit, with $n$ target wires and $n$ ancilla wires, we want to increment the target wires. And we want to do it with at most $O(n)$ Toffoli-or-smaller gates.

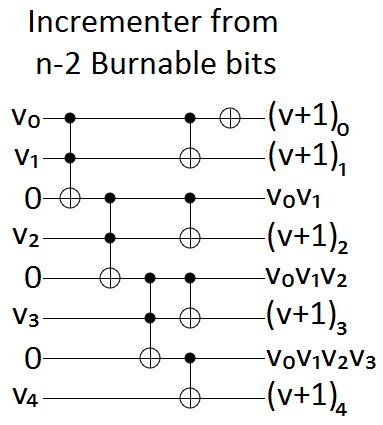

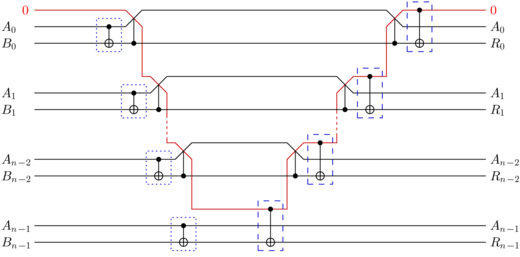

The burnable bits case only needs $n-2$ of the $n$ available ancilla bits. By using the burnable bits to accumulate the intersection of more and more controls, we get exactly the conditions we need for updating each target bit:

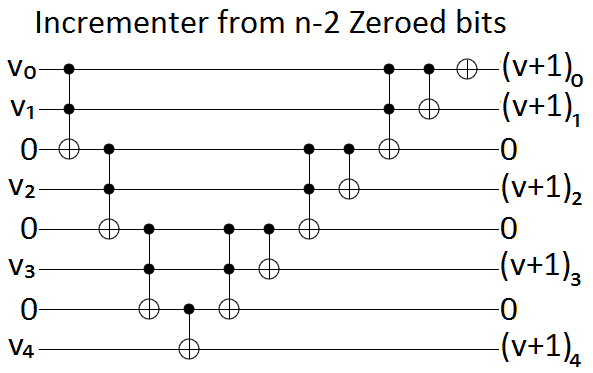

The zeroed bits case is solved by, as with the single bit case, taking the burnable bits solution and adding uncomputation. We simply sweep up after ourselves:

That leaves only the $n$ borrowed bits case.

I have to admit, this case gave me a hard time. I was stuck on it for a solid week, if not more, unable to come up with anything that worked. I can think of a few reasons I wasn't making progress. First, I was trying to make things work with $n-2$ ancilla bits, instead of $n$. Second, I was trying to avoid putting any temporary garbage into the bits. Those two constraints made it difficult, if not impossible, to propagate a useful invariant from bit to bit. Third, it's surprisingly hard to find help for this sort of problem. It's difficult enough and specific enough that you'll get few responses on forums or Q/A sites, yet easy enough that it's not going to be the title of a paper (making it hard to find pre-existing solutions).

Eventually, after spinning in circles for an embarrassing amount of time, I came across the VanRentergem adder (source of diagram):

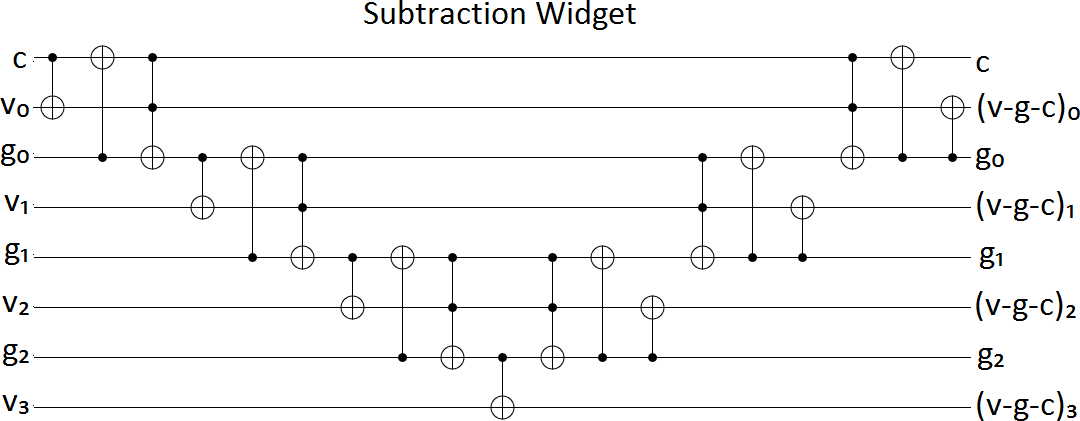

The VanRentergem adder takes a carry bit $c$, a two's complement value $a$, a two's complement value $b$, and turns $(c, a, b)$ into $(c, a, a+b+c)$. We'll use a tweaked version of the circuit, made out of Toffoli gates instead of controlled-swap gates, and reverse the gates so it does subtraction instead of addition:

With the above widget, we can subtract a garbage carry bit $c$ and a garbage two's-complement value $g$ out of our target value-to-increment $v$.

On its own, that subtraction seems like the wrong move to make. After all, it mixes a bunch of garbage into our target. However, we can use the bitwise complement trick from before to fix the problem. If we apply the subtraction widget again, but toggle $g$'s bits first, then the target bits will have transitioned from storing $v$ to storing $v-c-g$ to storing $v-c-g-(-g-1)-c = v-2c+1$. By getting rid of the garbage from $g$, we create the $+1$ we're trying to perform!

(Caution: because we're storing one more bit of $v$ than we are of $g$, adding $g$ and its complement will toggle $v$'s high bit. Put a NOT on the high bit to fix that problem.)

Now we need to get rid of the garbage from $c$.

Consider how $v-2c+1$ behaves for each possible value of $c$.

When $c$ is On we get $v \rightarrow v-2+1 = v-1$, meaning we decremented $v$.

When $c$ is Off we get $v \rightarrow v+1$, meaning we incremented $v$.

We always want to increment, and can easily turn a decrement into an increment by surrounding it with NOTs, so... just do that but conditioned on $c$.

What we end up with is two VanRentergem-style subtractions. The non-carry-bit garbage is cancelled out by toggling it before and after one of the subtractions. The carry bit garbage is cancelled out by pre- and post-toggling the target bits when the carry bit is On. Finally, because the target value has one more bit than the garbage value, the highest bit needs special handling. Overall, you get this:

With these asymptotically efficient $n$-ancilla-bit constructions in hand, we can fix the inefficiencies in our single bit constructions.

Putting It All Together

Basically all we need to do, to turn an $n$-bit increment with a single ancilla bit into a linear number of Toffoli-or-smaller gates, is apply the appropriate single bit construction and then apply the appropriate $n$ borrowed bit construction. However, there are a few caveats.

First, after the single bit construction has been applied, the largest remaining operation has size $\lceil \frac{n}{2} \rceil$ and therefore has access to at most $\lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor$ borrowable unaffected bits. Because $\lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor$ can be one less than $\lceil \frac{n}{2} \rceil$, we sometimes need to apply the single bit construction twice before the operations are small enough that we can borrow enough bits to apply the $n$ bit construction. Alternatively, because increments only have one controlled-not that touches all the relevant wires, we can pull that operation out of the increment (reducing the increment's bit size by 1) and handle it separately.

Second, the constructions make (a constant number of) controlled-not gates in addition to the created increment gates. You handle those by applying the construction from the large controlled-nots post.

Third, although this construction is asymptotically efficient, it has a large constant factor. I didn't do a careful analysis, but it seems that an $n$ bit increment turns into something like $32n$ Toffoli-or-smaller gates. There are probably solutions with better constant factors.

To make sure that the described construction actually works, I wrote some hacky python code to test it. Using that code to generate the 5-bit increment circuit, then crunching it down a little by hand so the thing fits on the page, gives:

a ────•─•─•••X•───────•X──•X•───────•X─••──•─•─•◦•X•───────•X──•X•───────•X─•◦X─X••───────••X─X••───────••XX─ a+1

│ │ │││││ ││ │││ ││ ││ │ │ │││││ ││ │││ ││ │││ │││ │││ │││ ││││

b ────•─•X┼┼┼•X•X•─•X─X••X┼•X•X•─•X─X••┼┼──•─•X┼┼┼•X•X•─•X─X••X┼•X•X•─•X─X••┼┼┼X┼┼┼X••─••X┼┼┼─┼┼┼X••─••X┼┼┼┼X b+a

│ │ ││││││││ ││ │││ ││││││ ││ │││││ │ │ ││││││││ ││ │││ ││││││ ││ │││││││││││││ ││││││ ││││││ ││││││││

c ───•┼•┼X┼┼┼┼┼┼•X◦X••┼┼┼X┼┼┼┼•X•X••┼┼┼┼┼─•┼•┼X┼┼┼┼┼┼•X•X••┼┼┼X┼┼┼┼•X•X••┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼X┼┼┼┼┼┼─┼┼┼┼┼┼X┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼ c+ab

││││ │││││││││││││││ │││││││││││││││ ││││ │││││││││││││││ ││││││││││││││││││││││││││││││ │││││││││││││││

d ─X•X┼X┼•┼X┼┼┼X••┼••X┼┼┼─┼┼┼X••┼••X┼┼┼┼X•X┼X┼•┼X┼┼┼X••┼••X┼┼┼─┼┼┼X••┼••X┼┼┼┼X┼┼┼•X•X•┼•X┼X••X┼•X•X•┼•X┼X••┼┼ d+abc

│││││││ │││ │ │││ │││ │ ││││ │││││││ │││ │ │││ │││ │ ││││ │││││ ││││││││ │││ ││││││││ ││

e X•X•X•XX┼•┼┼┼───X───┼┼┼─┼┼┼───X───┼┼┼┼•X•X•XX┼•┼┼┼───X───┼┼┼─┼┼┼───X───┼┼┼┼X┼┼┼┼┼─•X◦X••┼┼─X┼┼┼─•X•X••┼┼─┼┼ e+abcd

│ │││││ │││ │││ │││││ │││││ │││ │││ ││││ │││││ ││ │││ ││ ││

Z ─X──────XXX••───────••X─X••───────••XXXX─────XXX••───────••X─X••───────••XXX•••X•───────•X──•X•───────•X─•• Z

(I sure hope your browser renders monospaced unicode correctly, or that will look like a mess.)

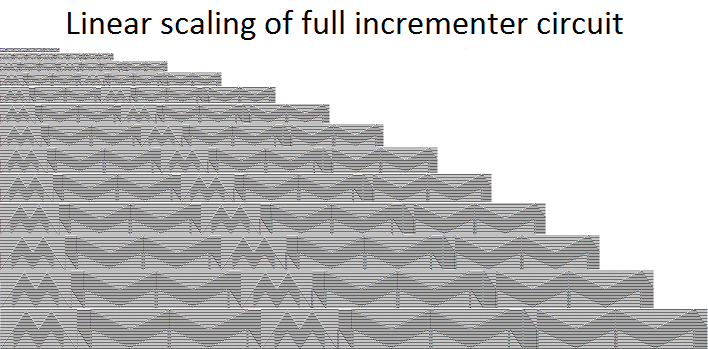

If you squint a bit, you can see hints of a pattern. To make that pattern very apparent, I printed incrementally larger and larger cases then zoomed out:

I guess this construction is creating some delicious circuits. mMMmMMMM. (I am so sorry. Please don't shun me.)

Summary

Given a single ancilla bit, in an unknown state that must be preserved, you can create $n$-wire increment gates using $O(n)$ Toffoli-or-smaller gates.

The key parts of the construction are the VanRentergem-style subtraction, and using bitwise complements to conditionally switch between adding and subtracting.

Next time: using quantum gates to bootstrap an ancilla bit out of nothing.

Navigation

Part 1: Constructing Large Controlled-Nots

Part 2: (This Post)

Part 3: Using Quantum Gates instead of Ancilla Bits