This series of posts began with the discovery a mistake, and an attempt to fix the problem. In this post, I give an insight into the problem that improves on the original result.

Part 1: Resynthesizing the circuits

Part 2: (this post) Reconceptualizing the distillation

Part 3: Rebraiding the factory

Switching strategies

In part 1 of this series, I showed how to make block code circuits that consume $8+3k$ noisy $|T\rangle$ states and produce $k$ less-noisy $|T\rangle$ states. Basically I guessed at some initial circuits based on figures in a 2012 paper by Bravi et al, and then rearranged the circuits in Quirk until I had something that looked pretty good.

Rearranging circuits is fun and all, but it does have its limitations. You can spend a lot of time wandering around circuit space not finding anything new. Fortunately, wandering has a funny way of teaching you the lay of the land; of giving you insights that can lead to new places. You make guesses as to what's really going on, test them out, and try to pull out conceptual insights. That's what we'll be doing in this post.

First, I'll explain what the block code circuit is actually doing. Then I'll show how to generalize the idea and apply it in another situation. Ultimately, this will lead to a distillation circuit that uses 4 fewer noisy $|T\rangle$ states while still producing the same number of output $|T\rangle$ states.

Looks like AND

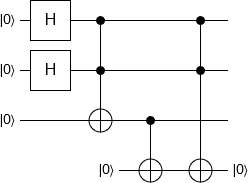

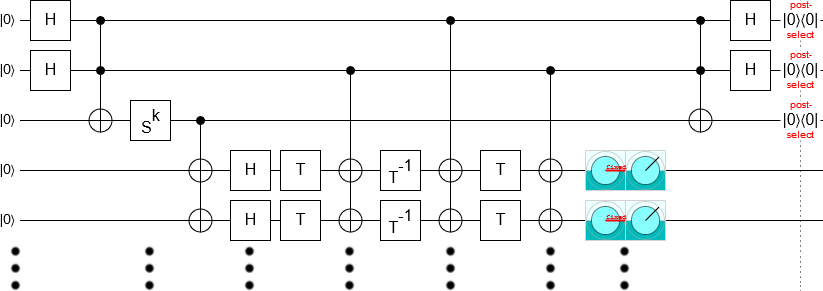

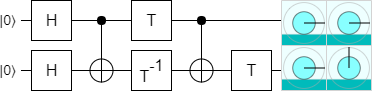

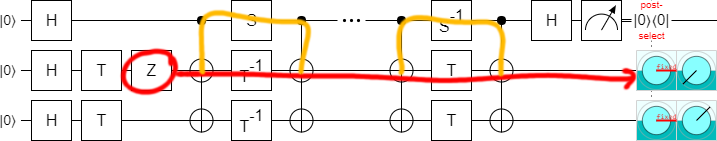

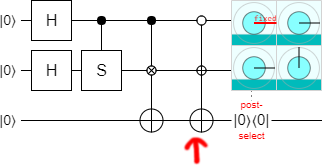

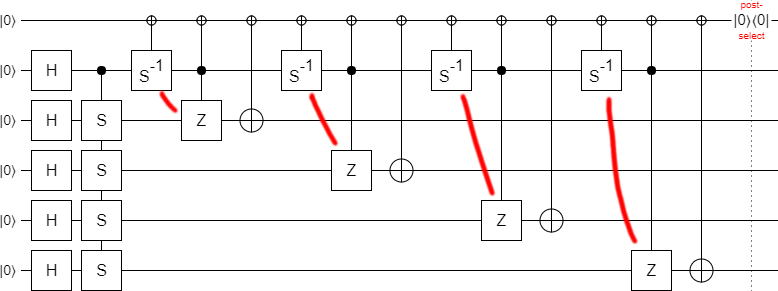

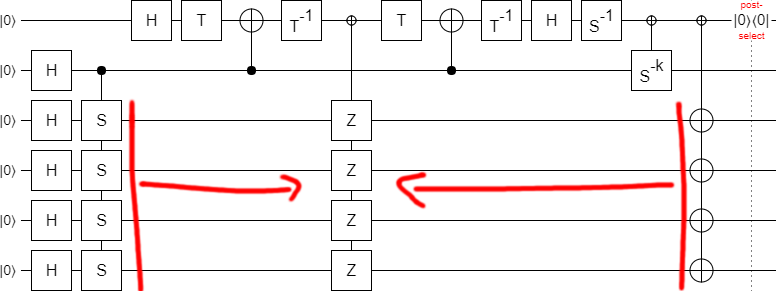

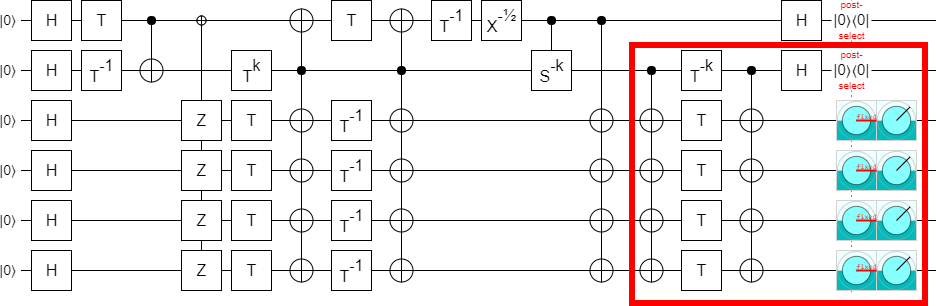

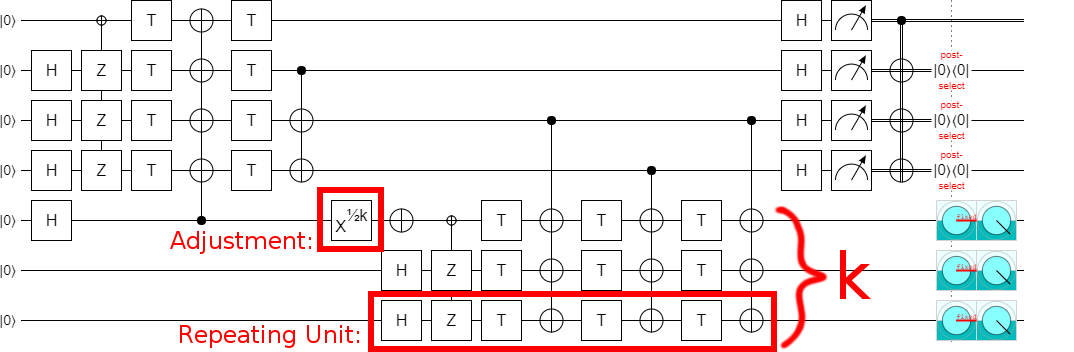

For reference, this is the final circuit from last time:

While working with the circuit in the part 1, I kept noticing patterns that I associate with Toffoli gates and AND gates.

Recall that we had figured out that the left half of the circuit is preparing a $|\overline{CCZ}\rangle$ state whereas the right half was consuming it. That was the first hint that this circuit has something to do with Toffoli gates. (A $|\overline{CCZ}\rangle$ resource state you can burn to apply a Toffoli.) In fact, although they look different on the surface, the left half of the circuit is equivalent to the "error detecting Toffoli" circuit from Cody Jones' 2012 paper "Novel constructions for the fault-tolerant Toffoli gate".

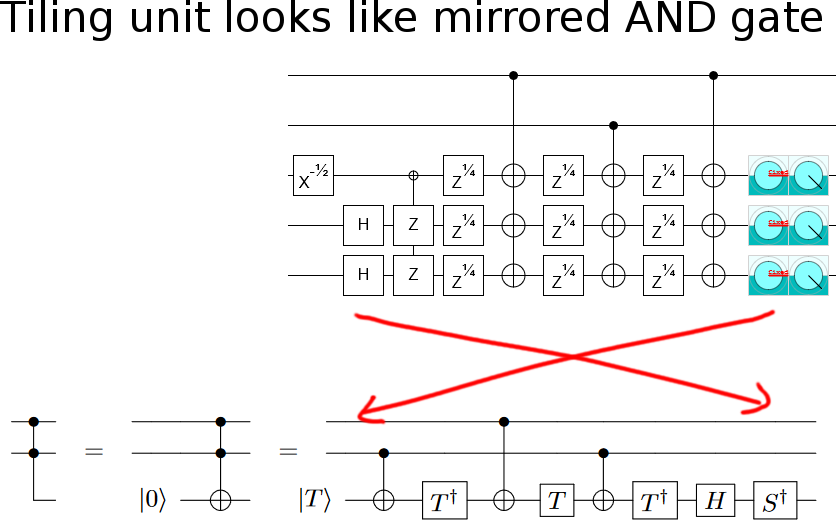

The second hint pointing towards Toffolis and ANDs is a bit more subtle, because it's just a visual similarity. The tiling unit from the final circuit is quite reminiscent of an AND computation, but in reverse:

If you reverse an AND computation, you get an AND uncomputation. When you uncompute an AND in this fashion, you recover a $|T\rangle$ state at the end (the opposite of investing a $|T\rangle$ state at the start). In an old version of my (now published!) paper "Halving the cost of addition", I used this observation to reduce the net T-count of an AND uncomputation from 4 to 2. (That was before I found out about how to do it without using any Ts at all).

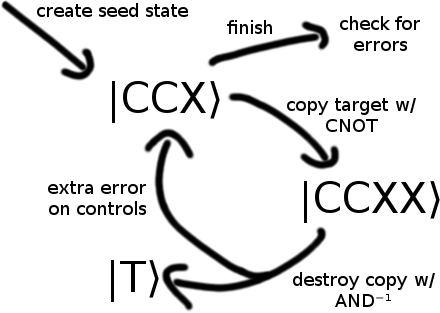

The fact that I was familiar with the concept of using an AND uncomputation to recover a $|T\rangle$ state, and the fact that the block code circuit looks like AND uncomputations recovering $|T\rangle$ states, made the key idea behind the circuit suddenly clear. What the block code circuit is really doing is computing the AND of two inputs, using CNOTs to make multiple copies of the AND output, then independently uncomputing each of the copies in a way that leaves behind a $|T\rangle$ state.

Let's go over why this works. Consider what happens to the bottom qubit in the following circuit:

The bottom qubit starts off as 0, then gets initialized to the value $a \land b$ by the CNOT operation (where $a$ is the top qubit's value and $b$ is the second qubit's value), then gets cleared back to 0 by the final Toffoli gate. Because the final Toffoli is clearing the qubit, it is actually an AND uncomputation. And if we do that AND uncomputation in the way that recovers a $|T\rangle$ state... well, we get a $|T\rangle$ state!

Now, at first glance, this seems like a terrible trade. Sure, we recovered a $|T\rangle$ state, but in order to recover the state we had to use three T gates (which consumes three $|T\rangle$ states). However, it just so happens that, if there is Z error in one the T gates that we apply, the error will kick back into one or both of the control qubits. As long as the controls are in a state that's sensitive to Z errors (which they are), we can detect this kickback later by measuring the controls. This error detection mechanism implies that the T gates we apply can be noisy, and that our output will be less noisy (since at least two of the input states must have undetected errors for the output state to have an undetected error).

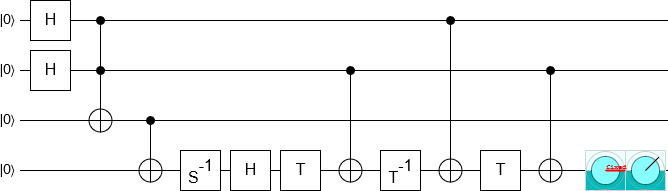

But here's the really fun part: we can just keep doing this again and again. Make a copy of $a \land b$ using a CNOT, destroy the copy with an AND uncomputation (kicking errors into the controls), recover a $|T\rangle$, and repeat. A neat little cycle:

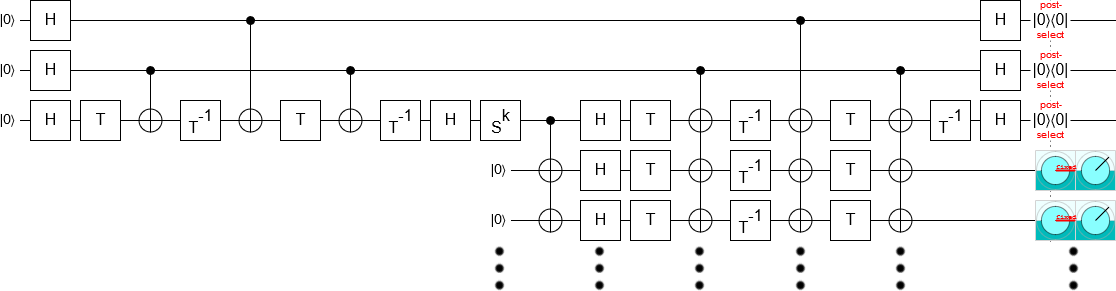

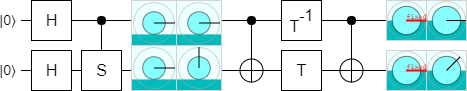

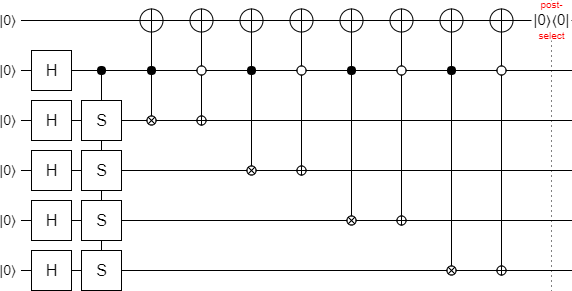

Which immediately implies a serial circuit construction:

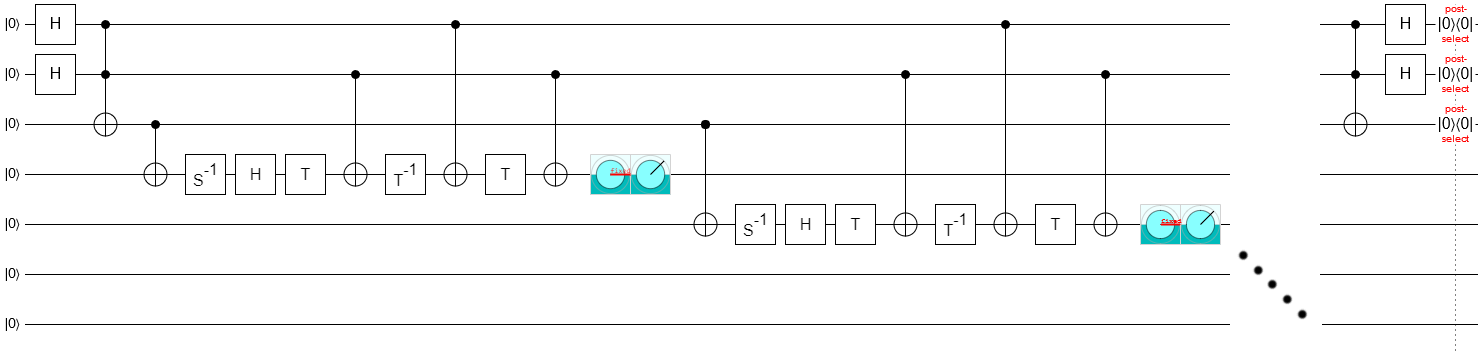

Of course, it's trivial to parallelize all of the steps:

And, because all of the ancilla qubits are being initialized to the same $a \land b$ value, all of the S gates on the left are phasing the same underlying value. The S gates can be combined into a single gate:

There's still one problem left. In order for this to be a circuit we can actually execute, we need to decompose the initial and final Toffoli gates into basic gates. More importantly, we need to detect if an error occurs while performing the Toffoli gate.

In Jones' 2012 paper, this is done by (effectively) computing the Toffoli twice and checking that they output the same answer. We're doing something slightly different: computing the Toffoli gate, using it, then uncomputing it (all the way; without recovering a $|T\rangle$ state) and expecting to get an OFF result. If there is a single Z error in one of the T gates, it will toggle the qubit we're storing the AND value in. We can detect that toggling by measuring the qubit after uncomputing the Toffoli: if it's ON, there was a problem.

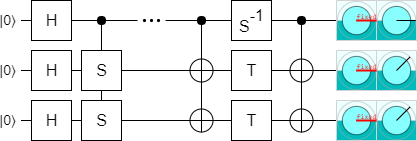

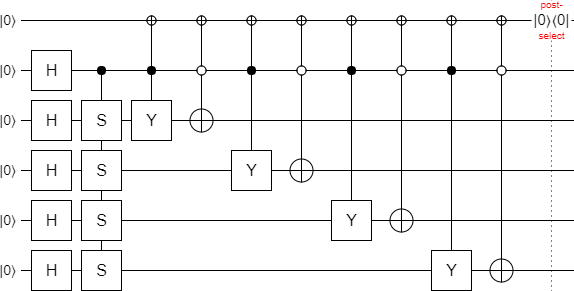

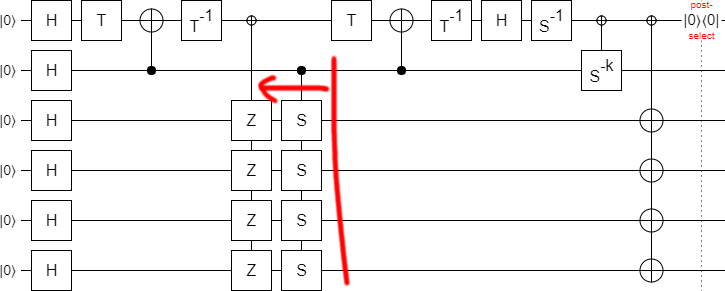

The Toffoli uncomputation can be done in parallel with all the partial uncomputations. The circuit to do so looks like this:

Now, to me, this circuit is quite frustrating to look at. Why is that part on the left all by itself, instead of being part of the big parallel chunk? Surprisingly, as long as you know the rules for propagating operations through Clifford computations, this is easy to fix. You propagate the four T gates rightward, and they slot right in. You do end up creating two new columns of operations in the process, but that tiny increase is dwarfed by the huge depth reduction achieved by running all of the Ts in parallel:

The above circuit is more compact than the one we ended up with last time. And it took less time to create, and to explain. This is pretty typical: when you understand what a circuit is really doing, it's suddenly a whole lot easier to synthesize and optimize the thing. (But don't forget that playing around with the circuit, without really understanding the high-level details, was crucial to achieving this understanding in the first place!)

Trying the same thing with CS states

At a high level, the circuit from the previous section a) computes a special state, b) verifies that state somehow, and c) leaves behind T states by partially uncomputing the special state in a way that kicks errors onto control qubits. We happened to use the special state $|CCX\rangle = |000\rangle + |010\rangle + |100\rangle + |111\rangle$, but there are other states that could conceivably work. Specifically, let's consider the $|CS\rangle = |00\rangle + |01\rangle + |10\rangle + i|11\rangle$ state.

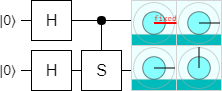

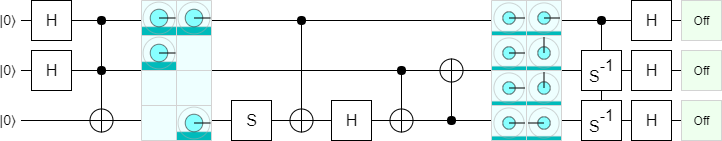

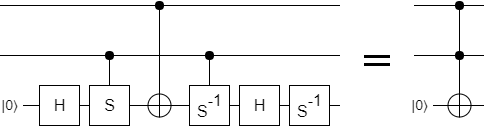

You can prepare a $|CS\rangle$ state by applying controlled-S gate to the state $|++\rangle$:

And you can decompose the controlled-S gate into three T gates and two CNOTs:

See that T gate at the end of the decomposition? That's a good sign. It means that, when we uncompute a CS state, we can stop short and recover a $|T\rangle$ state:

Another good sign is that we can tile this construction:

(Notice that the two T gates on the control qubit merged into an S gate. Controlled-S gates are much cheaper when they come in pairs with a common control.)

Yet another good sign is that we can detect errors. All of the T gates used during the uncomputation kick back into the control qubit. Any Z error on one of the T gates will toggle the output, allowing us to notice that something went wrong:

So, overall, this is extremely promising. But notice that the circuit still has undecomposed operations in it (the controlled-S gates on the left). Decomposing those operations will create T gates, and those T gates might have errors, and some of those errors aren't detected.

Here is an example of one of the errors that isn't detected, if we naively decompose the controlled-S in the usual way without doing anything else:

Basically, what we need is some way to produce CS states in an error-detecting way. If we can do that, then we can use the uncomputation strategy layed out in the above diagrams to pull T states out of the state while uncomputing it.

Special case: Turning $|CCX\rangle$ into $|CSS\rangle$

The first error-detected CSS I managed to make was the $k=2$ case. I've spent a lot of time thinking about Toffoli gate constructions, and as a result I knew offhand that it was possible to implement an AND gate with two CS gates (plus Cliffords gates):

And this made me wonder if there was some way to use a Toffoli to apply a CSS operation or create a CSS state. So I opened up Quirk, dragged things around for a bit, and found this:

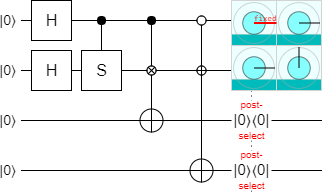

The above circuit is creating a $|CCX\rangle$ state and turning it into a $|CSS\rangle$ state with Clifford gates. By using this technique, and Jones' error-detecting Toffoli, we can prepare an error-detected $|CSS\rangle$ state. We then uncompute that state to get two T states:

Whoah! The block code circuit we derived last time has a production ratio of 14:2 (or 10:1). You had to invest 14 noisy T states to get 2 less-noisy T states. But the circuit above has a ratio of 10:2. We just made the construction more efficient!

When I first found this circuit, I thought I could use the same idea to easily improve the larger block code circuits. Basically, I would do the normal AND uncomputation thing for all but the last AND, where I'd use the convert-to-CSS-and-uncompute thing. Unfortunately, that doesn't work. The AND uncomputation and CSS uncomputation tricks are incompatible. The problem is that the AND uncomputation kicks errors onto both controls, but the CSS uncomputation only uses one of the controls as an error detector (it uses the other control as an output). When there's an error during one of the AND uncomputations, it can silently break the CSS uncomputation.

In order to generalize to larger sizes, we need to do something different: verification.

Checking $|CSS\rangle$ states

Suppose we have a noisy $|CS\rangle$ state. Is there a way to tell if it's broken or not? Clearly there are lots of things you could check, but what I tried was based on the following two facts:

- If the control qubit of a $|CS\rangle$ state is OFF, the target qubit should be in the $|+\rangle = |0\rangle + |1\rangle$ state.

- If the control qubit of a $|CS\rangle$ state is ON, the target qubit should be in the $|S\rangle = |0\rangle + i|1\rangle$ state.

Basically, for the verification process, I'm going to use a circuit that says "if q1 is OFF and q2 is $|-\rangle$, fail. Also, if q1 is ON and q2 is $|S\rangle^\dagger$, fail.". Here's a circuit that does that:

(Note: the little circle with a plus is an X-axis control, whereas the little circle with a cross is a Y-axis control.)

The above circuit is not perfect. It will detect a Z error on the target of the CS state, but not on the control. Errors on the control will instead be detected later, when we measure the control as part of the uncomputation.

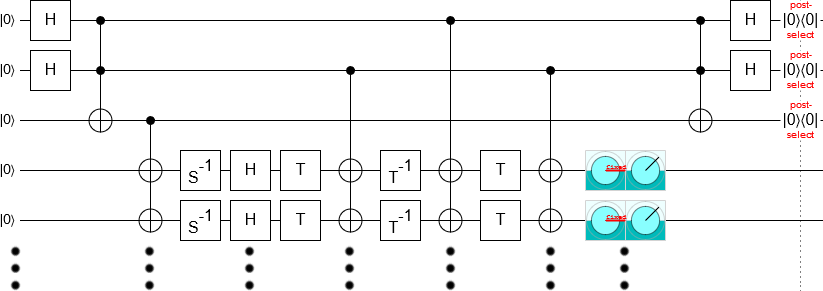

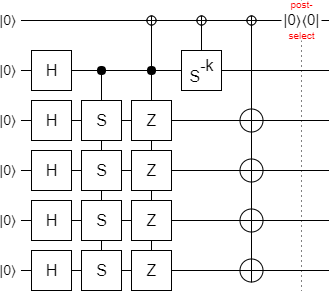

Because we only want to detect single errors, it's not necessary to use multiple check qubits. We can give both check operations the same target:

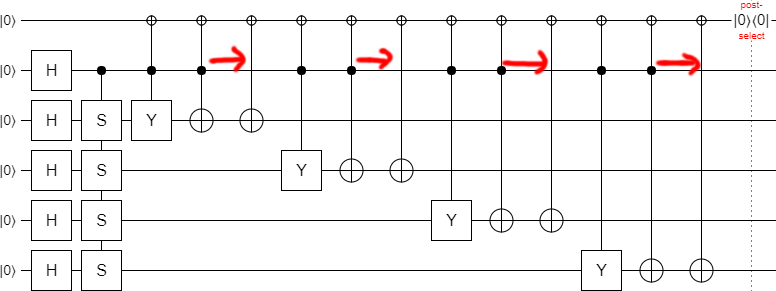

And, when we extend to having larger CSS states, we can continue to use the same target (which we'll place at the top so it doesn't get moved as we tile):

At the moment, this all looks incredibly inefficient. Every one of those three-qubit gates is going to require four T gates. But it turns out we can optimize them down into just one three-qubit operation.

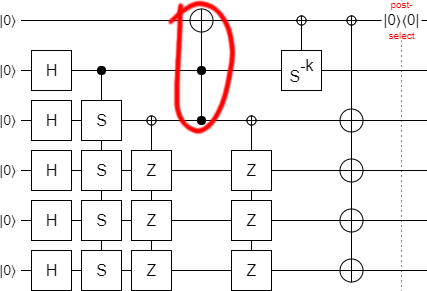

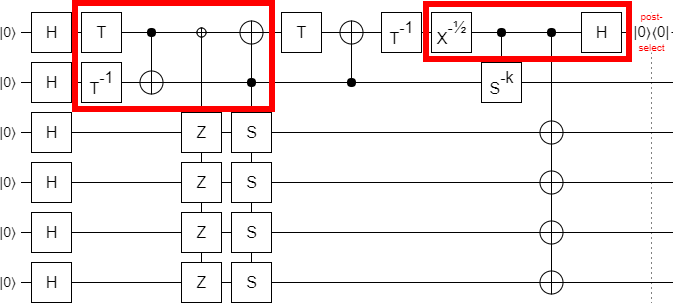

The first step of that optimization is to switch which qubit we're thinking of as the target. The following circuit is exactly equivalent to the previous one, just drawn differently:

Right now we have a mix of OFF controls and ON controls in the circuit, but to optimize further we need the controls to be consistent. So we flip each OFF control into an ON control by pulling out a two qubit operation:

A doubly-controlled X next to a doubly-controlled Y is just a doubly controlled $Y \cdot X = -iZ$. The $-i$ phase gets kicked onto the controls, producing two-qubit operations:

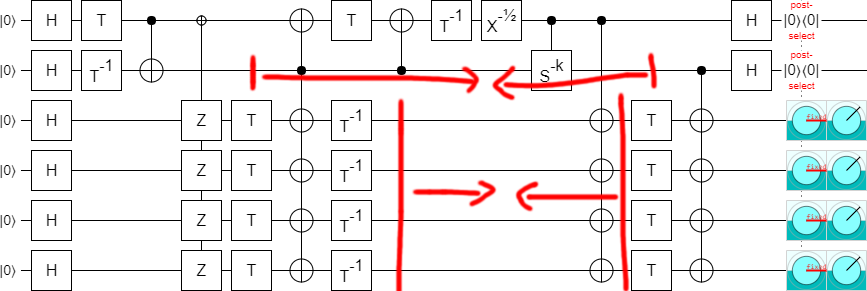

Now we merge operations. The four controlled $S^{-1}$ gates can be moved to the right hand side and combined into a single $S^{-k}$ operation. (Note that $k=4$ in our example and $S^4 = I$, but we aren't dropping the operation because we care about the general case not just the example $k=4$ case.) The controlled-NOT operations can be grouped together into a single multi-target operation. The doubly-controlled-Z operations can also be grouped into a single multi-target operation.

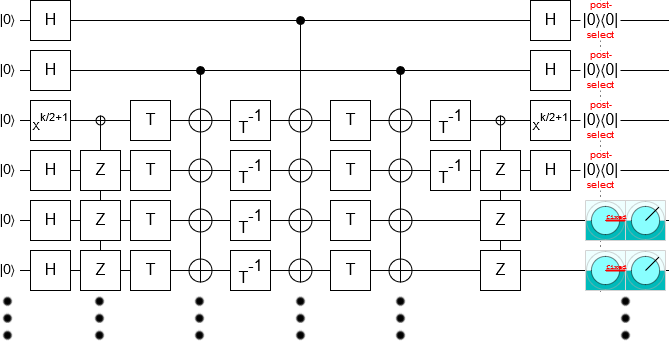

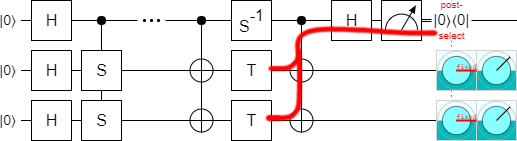

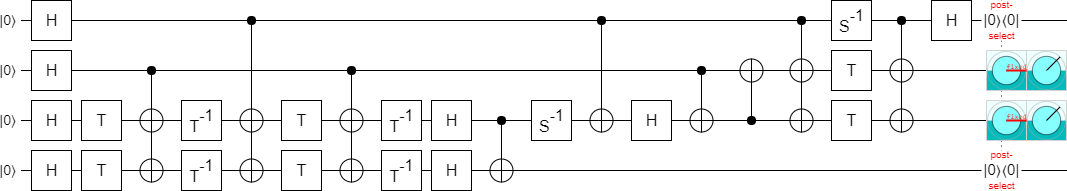

Here is the result of all that merging:

Then, using controlled-NOTs, we can reduce the multi-target three qubit operation into a normal Toffoli:

This completes the basic verification circuit. But does it work? Well... as long as $k$ is even. When $k$ is odd, we fail to detect some errors. So, from now on, we'll be assuming that $k$ is even. It's better for $k$ to be even anyways, since we'd have an extra controlled $S$ operation to do if $k$ was odd.

We have the bones; all we need to do now is work out the details.

Putting it all together

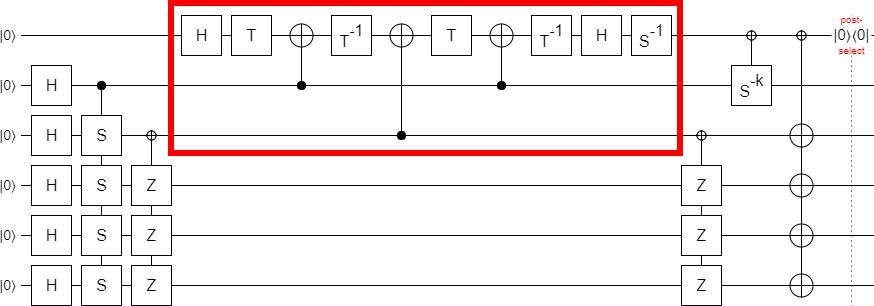

We need to decompose all of the operations in the verification circuit into the Clifford+T gate set. Then we need to add in the CSS uncomputation, so that we're actually recovering T states.

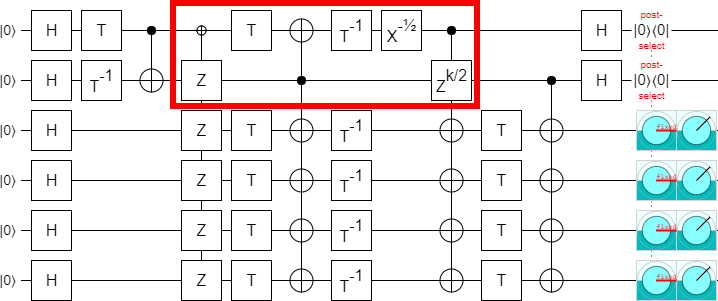

Let's start by expanding the Toffoli. Because its target is initially OFF, the Toffoli is actually an AND computation. Therefore we can decompose the Toffoli into an AND circuit:

We can merge some of the middle operations to reduce the clutter:

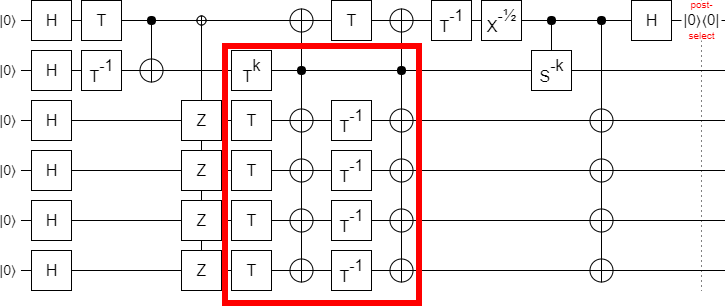

Then, with a bit of foresight, we move the controlled multi-Z operation leftward (pushing some T gates out of the way). (Because, as we will see in the next part, there's a nice way to braid the multi-Z operation when its targets are near the start of a circuit. When the targets are in the middle of the circuit, you need to use a less efficient braiding strategy.)

We'll do just a bit more tidying before expanding more operations. Note that CNOTs right after the initial layer of Hadamards are no-ops. We can abuse this fact to get the first two T gates into a single column. At the same time, we'll move the final Hadamard gate as far right as it can go:

Now decompose the controlled S gates:

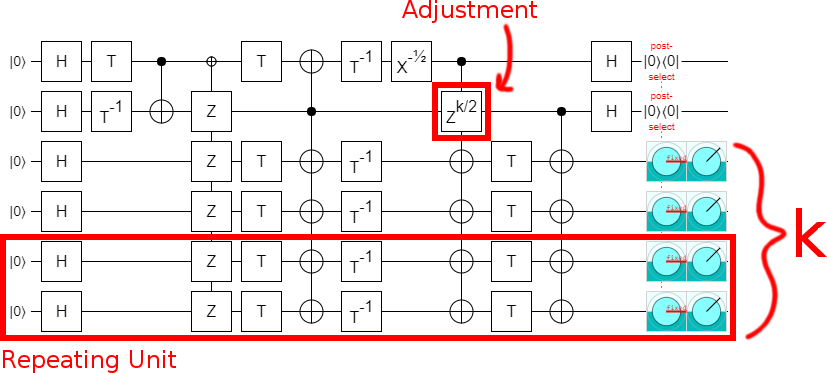

And add the missing part of the circuit, the partial CS uncomputations leaving behind T states:

A bunch of the stuff we just added can cancel against existing things. The $T^k$ cancels against the $T^{-k}$, and there's two nearly-adjacent CNOT columns with common targets and controls:

And we complete the circuit with a bit of cleanup:

And that's it! This is the final circuit:

Keep in mind that $k$ has to be even.

If you open that circuit in Quirk, and drag a Z gate around, you'll see that the post-selection fails whenever the Z is next to one of the T gates. Therefore the circuit is correctly detecting a single Z error on any T.

By counting the Ts, we see that the circuit uses $3k+4$ noisy T gates and produces $k$ less-noisy T states. The circuit from part 1 needed $3k+8$ T gates to do the same thing. We're producing just as many less-noisy T states, but paying 4 fewer T gates to do it.

Closing Remarks

The Bravi block code circuit is just a bunch of AND computations and uncomputations.

You can increase the efficiency of the block code circuit by basing it on controlled-Ss, instead of ANDs.

Any magic state that you can compute, check, and then partially uncompute is a T state factory waiting to be found.

When I tweeted about the circuit from in this post, Earl Campbell pointed out that he and Mark Howard had independently discovered the same ideas. This is one of the things I love about quantum computing: people beat me to ideas by months instead of decades.

Next time: turning the block code circuit into low-depth surface code braids.