Usually, pop science articles are terrible at explaining quantum anything. The breadth of their audience prevents them from going into detail, nevermind including an equation. I am under no such constraint, and in this series of posts ("[Un]popular Qubits") I look a bit more in-depth at quantum computing things reported by the media.

In this installment: quantum compression (example popular articles; the actual paper).

Foreword

Writing this post opened up a bit of a rabbit's hole for me. Because quantum information theory is sort of a work in progress right now, a lot of relevant concepts are only available in papers. Papers that don't explain things as well as text books do. I am still groping around trying to internalize the relevant information, and this post is part of that process.

So, keeping in mind that I'll try my best but am still toying with this, let's jump in.

Classical vs Quantum Compression

In classical computing, compression is used to make data smaller by removing redundancy. When you know some data will follow a pattern, there's opportunities to separate the how-it-follows-the-pattern parts from the how-it-deviates-from-the-pattern parts. By only transmitting or storing the latter, you save bandwidth and storage space.

Quantum compression has an analogous goal: given that some quantum data follows certain patterns, can you separate the follow-the-pattern parts from the deviates-from-the-pattern parts in order to only send the latter? The paper Quantum Data Compression of a Qubit Ensemble by Lee A. Rozema et al. answers in the affirmative, at least for qubits that are identical.

What does "qubits that are identical" mean? It means that the qubits are all interchangeable copies of each other. More specifically, the state of the qubits must be "invariant under permutation". If you shuffle the qubits, you're still in the same state.

Classically, this would be a really boring constraint. It would imply that either all of the bits were 0, or all of the bits were 1. Very easy to compress: send a bit to say if its 0s or 1s, and (when the size isn't obvious from the context or included in other overheads) then send $O(\log n)$ bits to say how many 0s or 1s there are.

Quantumly, things are more interesting. A qubit can be in the state $\ket{0}$ or the state $\ket{1}$, but it can also be in the state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{0} + \frac{i}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{1}$ or the state $\sqrt{\frac{3}{7}} \ket{0} - \sqrt{\frac{4}{7}} \ket{1}$ or generally any linear combination of the form $\alpha \ket{0} + \beta \ket{1}$ where $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are complex numbers satisfying $\left| \alpha \right|^2 + \left| \beta \right|^2 = 1$.

Another complication is entanglement. The qubits might be in a GHZ state like $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \parens{\ket{00000000} + \ket{11111111}}$, in a W state like $\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \parens{\ket{001} + \ket{010} + \ket{100}}$, or plenty of other possibilities. (Notice that, although the W state is invariant under permutation, the classical possibilities it is made up of are not! Tricky.)

To be honest, it's surprising to me that compressing these states is even possible. Quantum computing is filled with impossibility results that sound like they prevent exactly this sort of thing. For example, the no-deleting theorem says that (among other things) you can't merge two identical qubits into a single qubit with the same state. Another example is Liouville's theorem, which says that if your inputs cover a certain "volume" of space then no quantum operations can "squeeze" that into a smaller output volume.

Quantum compression skirts these impossibility results by not giving its output qubits "the same state" as its input qubits, and by only working for a comparatively small volume of inputs (i.e. the invariant-under-permutation ones). It can be done!

Method

One way to understand how quantum compression is possible is to look at how many unique amplitudes you get from expanding the $n$-identical-qubits state $\parens{\alpha \ket{0} + \beta \ket{1}}^N$. If we use the convention that $\ket{n \atop k}$ means "all the ways of having $k$ out of $n$ qubits can be ON", e.g. $\ket{3 \atop 2} = \ket{110} + \ket{101} + \ket{011}$, then the expanded form is $\Sum{k=0}{n} \ket{n \atop k} \alpha^k \beta^{n-k}$. Notice that, although there are $2^n$ states, there are only $n+1$ distinct weights being used.

Because all quantum operations are linear, and the distinct weights we're stuck with are not linear combinations of each other, there's no way for us to cancel the weights out. But we can move them around. In particular, we can re-arrange things so that the un-removable weights all end up on states where all but the first $\log \parens{n+1}$ qubits are OFF. This is guaranteed to be possible, with the main obstacle being figuring out how to do it. Or, more practically, how to do it efficiently and elegantly.

Fortunately for me, the paper says exactly how to go about re-arranging the amplitudes: apply a Schur-Weyl transform. The Schur-Weyl transform, roughly speaking, separates qubit space into permutation-related-parts and not-permutation-related-parts. Which sounds like exactly what we want, since our inputs happen to be invariant under permutation.

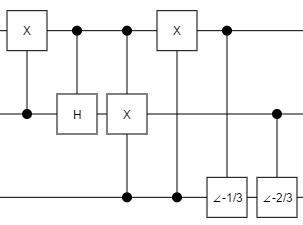

The paper even politely includes an example circuit, which I have tweaked slightly, that compresses 3 identical qubits into 2 qubits:

The circuit uses several controlled gates. Two are common (the NOT gate "X" and the Hadamard gate "H") and two are unusual.

The unusual gates, the ∠(-1/3) gate and the ∠(-2/3) gate, are rotation gates tuned to rotate from an amplitude where the qubit has a particular probability of being ON to an amplitude where the qubit is guaranteed to be OFF. The ∠(-1/3) gate's matrix form is $\begin{bmatrix} \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}} & \sqrt{\frac{1}{3}} \\ -\sqrt{\frac{1}{3}} & \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}} \end{bmatrix}$; a rotation matrix with angle of rotation $\theta = \sin^{-1} -\sqrt{\frac{1}{3}} \approx -35.264$ degrees. Analogously, the ∠(-2/3) gate rotates by $\theta = \sin^{-1} -\sqrt{\frac{2}{3}} \approx -54.736$ degrees. (Note that the ∠ symbol is definitely not standard; I just picked something vaguely related to rotations.)

The paper goes on to explain how they experimentally implemented that circuit as an optical system. Since I don't have the equipment for any of that, we'll have to settle for simulation.

Simulation

Using the toy quantum circuit inspector I've been working on lately, I tried feeding various invariant-under-permutation states through the circuit given by the paper. For example, here's an animation of what happens when the qubits are all gradually rotated around the X axis of the Block Sphere:

(Note that the rotation-to-quantum-operation mapping I'm using is the one I've discussed previously. Specifically, each qubit's pre-compressed state is following the curve $\psi(t) = \frac{1}{2} \parens{1 + e^{i t} } \ket{0} + \frac{1}{2} \parens{1 - e^{i t}} \ket{1}$.)

In the above diagram, the changing percentage indicators indicate how likely you would be to find that the covered wire was ON, if you measured said wire at that point (but the simulator is not actually performing a simulated measurement, since that would mess up the outputs). Note that, before compression, all three wires are varying but, after compression, only the first two are varying. The three qubit states are being mapped onto just two qubits.

Also note how the first output kind of swoops up to 50%, then slows down until the second output swoops to 100%, then itself swoops to 100%. That looks kind of neat.

I tried lots of other cases: rotating around the Y axis, combinations of X and Y and Z, entangled states, etc. The output probabilities swoop differently when things are entangled, but otherwise the various cases act similarly.

One interesting thing I noticed is how the output amplitudes behave as the input qubits are rotated. Here's an animation of the output amplitudes from the above circuit:

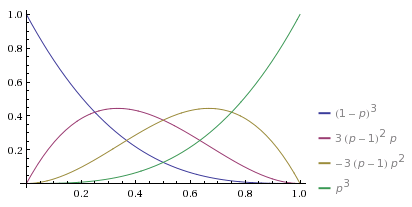

As the probability of each input wire being ON varies, the distribution of amplitudes appears to be tracking the probability of getting k heads with 3 biased coin flips!

The same thing happens for all the other inputs I tried, as long as they were invariant under permutation. Entangled states can even skip directly from 0 heads to 3 heads without passing through 1 and 2! It's like the compression circuit is sampling the qubits and counting how many of them are ON, despite not collapsing the superposition! Perhaps not useful, but definitely interesting.

So... this quantum compression thing seems to work. What can we use it for?

Applications?

When it comes to possible applications of quantum compression, my first instinct was "saving bandwidth". However, after thinking about it more, I'm not so sure. Quantum communications generally have two big benefits: better coordination, and better secrecy... but compression doesn't seem to work in either case. The other possible applications are space-saving and pedagogic.

Coordination

In a quantum coordination protocol, like the symmetry breaking protocol I discussed recently, you do often want to send several entangled qubits that are "identical". The problem is that it's the wrong type of "identical": you want the sent qubits to all be entangled with different kept qubits, and this violates the constraint that they be invariant under permutation. To make quantum compression to work, you'd have to entangle all of the sent qubits in the same way with the same kept qubit(s).

For example, there's no way to use quantum compression on bell pairs (i.e. those things used by every coordination protocol). Being able to compress $n$ bell pair parts into less than $n$ qubits would be amazing. Too amazing. It would let you recursively nest superdense coding inside of quantum teleportation and vice versa. Each level of nesting would slowly, but exponentially, increase the amount of information being sent when you set the whole process into motion. With a single bit you could send ten bits. With those ten a hundred. And so on indefinitely, increasing the entanglement-assisted classical capacity of basically any quantum channel to infinity. In other words: clearly not possible.

Even when we can compress and send a particular entangled state, it seems to be more efficient to send it in some other way. For example, suppose you want to send half the qubits of a GHZ state like $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \parens{\ket{00000000} + \ket{11111111}}$. Given just one of those qubits, the receiver can easily make more with a controlled-not from said qubit onto a fresh initialized-to-OFF qubit. Why would we send $\log n$ compressed qubits instead of one uncompressed qubit?

Another type of entangled state we might want to send is a W state like $\frac{1}{2} \parens{\ket{0001} + \ket{0010} + \ket{0100} + \ket{10000}}$. This case can also made trivial by only sending one qubit, and relying on the receiver to expand it into as many as needed.

We could assume that the receiver wasn't able to make or extend these complicated entangled states for themselves... but that's a very odd assumption, given that the receiver can implement the intricate gates involved in the decompression process!

There may be quantum coordination protocols that could benefit from quantum compression, but I can't think of any.

Cryptography

Could we use compression to make quantum cryptography protocols more efficient? The problem here is that cryptography abhors patterns and redundancy. Even classically, you must beware the dangers of combining compression with encryption.

Quantum cryptography relies heavily on limitations related to measuring quantum states. Sending a lot of copies removes this limitation: the receiver or eavesdropper could infer the secret state by measuring a subset of the copies, and start making good-enough copies on their own.

In other words, quantum compression sounds like a great way to ruin your cryptography instead of making it more efficient. I don't think they mix well.

Space

Quantum compression could be useful for reducing the space requirements of a quantum algorithm. Some algorithms may have not-needed-at-the-moment qubits that are identical, allowing the algorithm to temporarily compress them in order to fit other qubits into the computer (a big deal, given how slowly the number of qubits we can work with has been growing). In some cases you could even operate on the compressed representation.

Pedagogic

Quantum compression is surprising, enlightening, and engaging... at least it was for me. It demonstrates corner cases of a few impossibility theorems, it counts within a superposition, and it leads you deeper into useful parts of quantum information theory (like the Schur-Weyl transform). I think that, at the very least, makes it useful for teaching and learning.

Summary

When you have $n$ qubits whose combined state is invariant under permutation, a Schur-Weyl transform can re-arrange the state so that only the first $\log \parens{n + 1}$ qubits are used. This is analogous to how a Fourier transform of just-right low frequency data would also only require only the first few bits, except the Schur-Weyl transform works in a more surprising situation.

Quantum compression may be useful as a tool for making a quantum algorithm more space efficient. I don't think it's useful for saving bandwidth, because cryptography abhors redundancy and quantum coordination requires entanglement that varies under permutation.